Boston City Hall

Coordinates: 42°21′37.16″N 71°3′28.68″W / 42.3603222°N 71.0579667°W

Boston City Hall is the seat of city government of Boston, Massachusetts. It includes the offices of the mayor of Boston and the Boston City Council. The current hall was built in 1968[1] to assume the functions of the Old City Hall, and is a controversial[2] and prominent example of the brutalist architectural style.[3] It was designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles (architects) with Campbell, Aldrich & Nulty (architects) and Lemessurier Associates (engineers).[4][5][6] Together with the surrounding plaza, City Hall is part of the Government Center complex, a major urban redesign effort in the 1960s.

Most modern opinions of the building are negative, often calling it one of the world's ugliest buildings. A 1976 poll of architects, historians and critics conducted by the American Institute of Architects, however, listed the Boston City Hall with Thomas Jefferson's University of Virginia campus and Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater as one of the ten proudest achievements of American architecture in the nation's first two hundred years.[7]

Contents

Architecture[edit]

Design[edit]

| This subsection needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Boston City Hall was designed by Gerhard Kallmann, a Columbia University professor,[1] and Michael McKinnell, a Columbia graduate student,[1] (who co-founded Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles) who won an international, two-stage competition in 1962. Their design, selected from 256 entries by a jury of prominent architects and businessmen, departed from the more conventional designs of most of the other entries—typified by pure geometrical forms clad with sleek curtain walls—to introduce an articulated structure that expressed the internal functions of the buildings in rugged, cantilevered concrete forms. Hovering over the broad brick plaza, the City Hall was designed to create an open and accessible place for the city's government, with the most heavily used public activities all located on the lower levels directly connected to the plaza. The major civic spaces, including the Council chamber, library, and Mayor's office, were one level up, while the administrative offices were housed above these, behind the repetitive brackets of the top floors.[citation needed]

At a time when monumentality was seen as an appropriate attribute for governmental architecture, the architects sought to create a bold statement of modern civic democracy, placed within the historic city of Boston. While the architects looked to precedents by Le Corbusier, especially the monastery of Sainte Marie de La Tourette, with its cantilevered upper floors, exposed concrete structure, and its similar interpretation of public and private spaces, they also drew from the example of Medieval and Renaissance Italian town halls and public spaces, as well as from the bold granite structures of 19th-century Boston (including Alexander Parris' Quincy Market immediately to the east).[8]

Many of the elements in the design have been seen as abstractions of classical design elements, such as the coffers and the architrave above the concrete columns. Kallmann, McKinnell, and Knowles collaborated with two other Boston architectural firms and one engineering firm to form the Architects and Engineers for the Boston City Hall, responsible for construction, which took place from 1963 to 1968.

The designers designed City Hall as divided into three sections, aesthetically and also by use. The lowest portion of the building, the brick-faced base, which is partially built into a hillside, consists of four levels of the departments of city government where the public has wide access. The brick largely transfers over to the exterior of this section, and it is joined by materials such as quarry tile inside. The use of these terra cotta products relates to the building's location on one of the original slopes of Boston—expressed in the open, brick-paved plaza—and also to historic Boston's brick architecture, seen in the adjoining Sears Crescent block and the Blackstone Block buildings across Congress Street.

The intermediate portion of City Hall houses the public officials: the Mayor, the City Council members, and the Council Chamber. The oversize scale and the protrusion of these interior spaces on the outside—instead of burying them deep within the building—reveal these important public functions to the passerby, and create a visual and symbolic connection between the city and its government. The effect is of a small city of concrete-sheltered structures cantilevered above the plaza: large forms that house important civic activities. The cantilevers are supported by exterior columns, spaced alternately at 14-foot-4-inch (4.37 m) and 28-foot-8-inch (8.74 m), which are steel-reinforced.

The upper stories contain the city’s office space, used by civil servants not visited frequently by the public, such as the administrative and planning departments. This bureaucratic nature is reflected in the standardized window patterns, separated by pre-cast concrete fins, with an open office plan typical of modern office buildings. (The subsequent enclosure of much of this space into isolated offices contributed to the ventilation problems of these floors.)

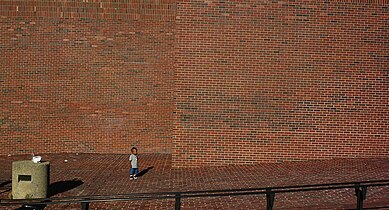

The top of the brick base was designed as an elevated courtyard melding the fourth floor of the city hall with the plaza. Because of security concerns, city officials in recent years blocked access to the courtyard and to the outdoor stairways to Congress Street and the plaza. The courtyard is occasionally opened up for events (such as the celebration of the Boston Celtics championship in 1986). After 9/11 security was further increased. City Hall's north entrance facing the plaza was barricaded with jersey barriers and bicycle racks. All visitors entering the front and back entrances must pass through metal detectors.

City Hall was constructed using mainly cast-in-place and precast Portland cement concrete and some masonry. About half of the concrete used in the building was precast—roughly 22,000 separate components—and the other half was poured-in-place concrete. All of the concrete used in the structure, excluding that of the columns, is mixed with a light, coarse rock. While the majority of the building is created using concrete, precast and poured-in-place concrete are distinguishable by their different colors and textures. For example, cast-in-place elements are coarse and grainy textured because the concrete was poured into fir wood frames to mold it, while precast elements, such as trusses and supports, were set in steel molds to gain smooth, clean surfaces. This distinction can also be seen in the fact that the exterior poured-in-place pieces are of type I cement, a lightly colored cement, while the exterior precast components use type II cement, a dark colored cement. The base of the building is dark with brick, Welsh quarry tiles, mahogany walls, and darker concrete. As the building ascends, the overall color lightens, as lighter concrete is used.

Reception of the building[edit]

Public response to Boston City Hall remains sharply controversial. Arguments for and against the structure's continued existence continue to provoke strong counter-arguments, from politicians, local press, design professionals, and the general public.

Positive reception[edit]

|

|

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

While assessment of the building's architecture has followed the vagaries of architectural style, the building was acclaimed by some architects such as the American Institute of Architects, which gave the building its Honor Award in 1969.[9] City Hall was awarded two stars by the Michelin Green Guide, which wrote that the building "has been one of Boston's controversial architectural statements since its completion in 1968."[10]

Representative of its acclaim was the opinion of New York Times critic Ada Louise Huxtable, who wrote that "in this focal building Boston sought, and got, excellence."[11] Historian Walter Muir Whitehill wrote that "it is as fine a building for its time and place as Boston has ever produced. Traditionalists who long for a revival of Bulfinch simply do not realize that one does not achieve a handsome monster either by enlarging, or endlessly multiplying, the attractive elements of smaller structures."[12]

Architect, educator, and writer Donlyn Lyndon wrote in The Boston Globe that "Boston City Hall carries an authority that results from the clarity, articulation, and intensity of imagination with which it has been formed."[13] Architectural historian Douglass Shand-Tucci, author of Built in Boston: City and Suburb, 1800–2000, called City Hall "one of America's foremost landmarks" and "arguably the great building of twentieth-century Boston." In the AIA Guide to Boston, Susan and Michael Southworth wrote that "the award-winning City Hall had established its architect's reputation and inspired similar buildings across the nation."[14]

Stylistically, City Hall is considered by a few one of the leading examples of what has been called Brutalist architecture. It is listed among the "Greatest Buildings" by Great Buildings Online, an affiliate of Architecture Week.[15] Additionally, in a 1976 Bicentennial poll of historians and architects regarding America's greatest buildings, sponsored by the American Institute of Architects, Boston City Hall received the sixth most mentions.

When Boston's Mayor Menino stirred controversy with his discussion of selling City Hall (see below), the building elicited renewed recognition[who?] for its influence, its design originality, and its symbolism of Boston's rebirth in the 1960s. The Boston City Landmarks Commission received an extensive application for the building's landmark status, including supporting signatures and letters from architecture critic Jane Holtz Kay, Friends of the Public Garden President Henry Lee, and others.[16] The Boston Globe published editorials recognizing the building's importance. Architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable penned an article for The Wall Street Journal[17] contrasting the poor treatment of Boston City Hall with Yale University's recent sympathetic restoration of its similarly challenging concrete landmark, the Art and Architecture Building by architect Paul Rudolph. A major exhibition of the original design drawings for City Hall—now part of the archive of Historic New England—was mounted at the Wentworth Institute of Technology.[18]

Negative reception[edit]

In the 1960s, then-Mayor John F. Collins reportedly gasped as the design was first unveiled, and someone in the room blurted out, "What the hell is that?"[20] City Hall is sharply unpopular with some Bostonians, as it is with some employees of the building, who see it as a dark and unfriendly eyesore.[21] In part, these opinions are a reaction against greater Boston's numerous examples of concrete modernism from the 1960s; with City Hall being one of the very few public buildings in the Brutalist style, it naturally receives more attention. In part, these opinions are influenced by the building's long-term inadequate funding for maintenance (compared to the Boston Public Library, for instance), its need for upgraded lighting and mechanical systems, its lack of coherent signage, and its post-9/11 security barriers and closed entrances.

The building's popularity declined as the tide turned away from a generation of modernism in New England to more traditional and post-modern styles in the 1970s and 1980s, as the newness wore off, as architectural monumentality fell out of vogue, and as the idea of a "new" era and a "new" Boston became old-fashioned. The changes in style coincided with political changes, as Kevin White's administration ended. Under subsequent administrations, when the focus became neighborhoods in place of the center city—decentralization instead of centralized civic power—funding was funneled away from City Hall. Compared to the well-maintained Boston Public Library, a place characterized by brightness, cleanliness, and warmth, City Hall's spaces suffer dramatically. In this context, some users and occupants have found City Hall unpleasant, dysfunctional, and dispiriting. It is the butt of jokes in some local magazines.[22] The structure's complex interior spaces and sometimes confusing floor plan are not mitigated through quality way-finding, signage, graphics or lighting.

Additionally, City Hall's large open spaces, central courtyard, and concrete structure make the building expensive to heat in an age of rising energy costs (although numerous public, institutional, and religious buildings throughout greater Boston feature similarly large, or larger, open spaces). As with other structures of its era, City Hall would benefit from a thorough study of ways to "green" the building and reduce its energy requirements while taking care to retain its dramatic design and key characteristics.

In 2008, the building was voted "World's Ugliest Building" in a casual online poll by a travel agency, which was picked up by a number of news outlets and embraced as a boon to tourism by Mayor Menino.[23][24] A 2013 newspaper article described it as "the worst building in the city" and advocated demolition.[25]

Reception of the plaza[edit]

The surrounding City Hall Plaza has experienced a similar change in assessment over time. Although its recessed fountain, trees, and umbrella-shaded tables drew crowds in the early years, more recently the space has been cited as problematic in terms of design and urban planning. To illustrate the range of opinion regarding the Plaza, in 2004 the Project for Public Spaces identified it as the worst single public plaza worldwide, out of hundreds of contenders,[26] and has placed the plaza on its "Hall of Shame."[27] On the other hand, in 2009, The Cultural Landscape Foundation included City Hall Plaza as one of thirteen national "Marvels of Modernism" in its exhibition and publication.[28] Several rounds of efforts to liven up City Hall Plaza have yielded only minimal changes, with the challenge being, in part, the numerous approvals required at the city, state and federal level.

Proposed modifications, including relocation/demolition[edit]

Since 2006, a number of proposals have been made to either modify City Hall or to demolish it and replace it with a new building on another site.

On December 12, 2006, Boston Mayor Thomas Menino proposed selling the current city hall and adjacent plaza to private developers and moving the city government to a site in South Boston.[29][30]

On April 24, 2007, the Boston Landmarks Commission reviewed a petition[31] backed by a group of architects and preservationists to grant the building special landmark status (much to the dismay of Mayor Menino).

On July 10, 2008, a Landmarks Commission official said the petition to grant the building special landmark status had been recommended for study, but probably would not be considered by the panel unless a plan to demolish the structure was imminent. Members of the group Citizens for City Hall also opposed Mayor Menino's plan to build a new City Hall on the South Boston waterfront because it would be a major inconvenience for tens of thousands of city residents.[32]

In December 2008, Menino suspended his plan to move City Hall. In a worsening recession, he stated, "I can't consciously move ahead on a major project like this at this time".[33]

An advocacy group, Friends of Boston City Hall,[34] was established to help develop support for preserving and enhancing City Hall, and improving the Plaza.

In 2010, the Boston Society of Architects held a competition for ideas for modifying City Hall.[35]

In March 2011, plans were announced to re-think the building and its surrounding plaza.[36][37]

California Home + Design has placed Boston City Hall on its list of "25 Buildings to Demolish Right Now."[38]

In 2015, the City of Boston launched a "Rethink City Hall" program to gather ideas for changes to the building and to City Hall Plaza.[39][40]

Events near the building[edit]

City Hall is located in Government Center in downtown Boston. The adjoining 8-acre (3.2 ha) City Hall Plaza is sometimes used for parades and rallies; most memorably, the region's championship sports teams, the Boston Celtics, Boston Bruins, New England Patriots, and the Boston Red Sox, have been feted in front of City Hall. A huge crowd in the plaza also greeted Queen Elizabeth II during her 1976 Bicentennial visit, as she walked from the Old State House to City Hall to have lunch with the Mayor.

As of May 2013, the plaza surrounding City Hall has been home to the biannual three-day Boston Calling music festival, which takes place in both May and September each year.

Image gallery[edit]

-

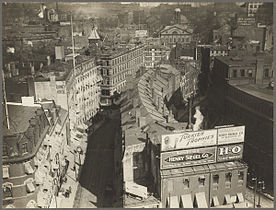

Brattle St., 1855 (future site of City Hall), photo by Southworth & Hawes

-

Overview, 1973, with distant view of Old North and I-93 (at left), and Faneuil Hall (at right)

-

Boston City Hall during the 2004 rally for the New England Patriots

-

City Hall, with view of overscale portrait of John F. Collins, mayor of Boston 1960–1968

See also[edit]

|

History of Boston's municipal government:

|

History of the site: |

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Hevesi, Dennis (2012-06-24). "Gerhard Kallmann, Architect, Is Dead at 97". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ "Throwback Thursday: When Boston’s City Hall Was New (and Already Unloved)", Boston Magazine, February 13, 2014, retrieved February 13, 2014

- ^ "Kallmann McKinnel & Knowles / Campbell, Aldrich & Nulty: Boston City Hall". #SOSBRUTALISM. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ^ [1] Archived guided tour pamphlet for Boston City Hall, published by Boston City Council

- ^ [2]

- ^ "Boston City Hall". DoCoMoMo-US.org. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-17. Retrieved 2013-12-17. Synopsis of AIA Polls

- ^ "The New Boston: City Hall," Charles W. Millard, The Hudson Review Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring, 1970), pp. 110-115

- ^ "Boston City Hall". American Institute of Architects. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "Boston City Hall". The Green Guide. Michelin Travel. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (11 September 1972). "New Boston Center: Skillful Use of Urban Space". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Freeman, Donald (1970). Boston Architecture. The MIT Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0262520157.

- ^ Lyndon, Donlyn (18 March 2007). "Why City Hall is worth saving". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Southworth, Susan; Southworth, Michael (2008). AIA Guide to Boston (3rd ed.). Globe Pequot Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7627-4337-7.

- ^ "Boston City Hall listing on Great Buildings Online". Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ^ "Boston City Hall Landmark Petition Form" (PDF). Friends of Boston City Hall. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (25 February 2009). "The Beauty in Brutalism, Restored and Updated". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Wolf, Gary, "Inventing a City Hall" Historic New England, Winter/Spring 2009

- ^ Paul McMorrow (September 24, 2013). "Boston City Hall should be torn down". The Boston Globe. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, Jack (2004-10-13). "'I wanted something that would last'". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ "The civic heart of the city" at Boston.com

- ^ Weekly Dig, May 2008

- ^ Boston City Hall tops ugliest-building list. The Boston Globe

- ^ reuters.com Travel Picks: 10 top ugly buildings and monuments

- ^ The Boston Globe City Hall Should Torn Down 2013/09/23

- ^ "15 Squares Most in Need of Improvement". Project for Public Spaces. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "City Hall Plaza - Hall of Shame". Project for Public Spaces. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ http://tclf.org/sites/default/files/landslide/2008/boston/index.html

- ^ "Menino proposes selling City Hall". Boston Globe. 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ^ Beam, Alex (2006-12-18). "Wrecking ball tolls for City Hall". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

- ^ "Landmark Petition" (PDF). Friends of Boston City Hall.org. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Embattled City Hall defenders change strategy" at Boston.com

- ^ Maura Webber Sodivi (2008-12-17). "Recession, It Seems, Can Fight City Hall; Relocation Is on Hold". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Friends of Boston City Hall". Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ Yang, Lin. "Re-imagining Boston's City Hall Building". SHIFTBoston Blog. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Casey Ross. A 10-year plan for City Hall Plaza: New incremental approach starts with remodeled T station, trees. Boston Globe, March 16, 2011

- ^ What do you think should be done to City Hall Plaza? Boston Globe, March 16, 2011

- ^ http://www.californiahomedesign.com/inspiration/25-buildings-demolish-right-now/slide/5074

- ^ "Rethink City Hall". City of Boston. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Mayor Walsh Announces Launch of RethinkCityHall.org, Inviting the Public to Help Reimagine the Future of City Hall and the Plaza". City of Boston. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- Tilo Schabert (1989). Boston Politics: the Creativity of Power. de Gruyter Studies on North America. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-084706-2.

- "Contest aims to enliven public spaces in Boston", Boston Globe, June 5, 2014

- Harry Bartnick (July 25, 2015), "Give Boston’s City Hall a much-needed makeover", Boston Globe

- "Mayor Walsh saves tax dollars in City Hall kitchen renovation but raises questions", Boston Globe, August 10, 2015

- "Mayor decides it’s time to brighten up dreary City Hall", Boston Globe, January 23, 2016

- "Four centuries of Boston flops, flubs, and failures", Boston Globe, July 26, 2016,

1968: Hall of Shame

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boston City Hall. |

- Official City of Boston website

- iBoston on Boston City Hall

- Brutalized in Boston, a critical review of the building

- CityMayors feature on Boston City Hall

- Complaints about Boston City Hall, concerning sick building syndrome

- Flickr. City Hall meeting on 311 in Boston, 2008

- Renderings of City Hall from Google 3D Warehouse

- Friends of Boston City Hall

- Structurae.net article

- docomomo-us article

- #SOSBrutalism website listing