Fort Negley

|

Fort Negley

|

|

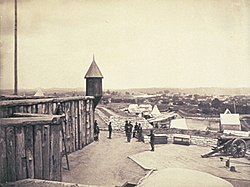

Fort Negley in 1864

|

|

| Location | 1100 Fort Negley Blvd. Nashville, Tennessee |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Nashville, Tennessee |

| Coordinates | 36°08′42.35″N 86°46′28.77″W / 36.1450972°N 86.7746583°WCoordinates: 36°08′42.35″N 86°46′28.77″W / 36.1450972°N 86.7746583°W |

| Area | 180,000 sq ft (fort only) |

| Built | 1862 |

| Architect | James St. Clair Morton |

| NRHP Reference # | 75001748 |

| Added to NRHP | April 21, 1975 |

Fort Negley was a fortification built for the American Civil War, located approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) south of downtown Nashville, Tennessee. It was the largest inland fort built in the United States during the war.[1]

History[edit]

Once Confederate forces were routed from Forts Henry and Donelson (on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, respectively), in February 1862, Confederate commanders decided that any further effort in the defense of Nashville would be pointless, and they abandoned any attempt to keep Nashville behind their lines. It was almost immediately occupied by Union forces, who rapidly began preparations for its defense. The largest of the fortifications erected was Fort Negley, a star-shaped limestone block structure atop a hill south of the city. The construction of the fort was overseen by Captain James St. Clair Morton. The fort was constructed out of 62,500 cubic feet of stone, 18,000 cubic feet of earth and cost $130,000.[2] It was largely constructed using the labor of local slaves (including women), newly freed slaves who had flocked to Nashville once it was taken by Union forces with the understanding that their status as slaves was to be revoked were they to work for the Union, and by free blacks forcibly conscripted for the work. Records show that 2,768 blacks were officially enrolled in its construction.[3] During construction 600-800 men died and only 310 ever received any pay.[4] The fort was named for Union Army commander General James S. Negley.

Interestingly, when the Battle of Nashville finally began in December 1864, it was largely fought on the heights even farther south of the city than Fort Negley, which despite its then-impressive appearance never played a leading military role. Shortly after the war, the fort was abandoned and fell into ruin; however, its outline could be readily discerned for many years afterwards in the encroaching woods. During the Reconstruction period, the area was used as a meeting place for the Ku Klux Klan.

Preservation[edit]

In the 1930s the Works Progress Administration (WPA) made a major project of the restoration of Fort Negley. However, almost simultaneous with the completion of this project came the United States' entry into World War II. Neither the manpower, funds, or the interest was available at the time to reopen the fort as an historic or interpretative center. After the war, the fort was allowed to continue to languish, becoming the site of vandalism, and minor crime; entry to the site was finally prohibited and the area reverted to forest. However, the surrounding grounds became the site of a municipal park, first as the site of baseball and softball fields for youth and adult leagues and later as the site of Herschel Greer Stadium, a minor league ballpark. The Cumberland Science Museum, a continuation under a new name and in a new venue of the former Nashville Children's Museum (now called Adventure Science Center), was built on the slope opposite the ballpark. Most visitors to the stadium and the museum were generally unaware of what was on the wooded hilltop other than it was something which they were not allowed to access.

After years of discussions and negotiations, historic preservationists were successful in getting sufficient funding in the early 2000s (decade) for another restoration project, and the fort was reopened to the public for the first time in decades on December 10, 2004. The project went ahead when it was shown that similar places in other cities resulted in more economic stimulation and hence more tax revenue from the resultant tourism than was spent on the maintenance and operation of such sites. The recent restoration was not an attempt to restore the fort completely to its Civil War condition but rather to stabilize the ruins and make them more accessible and visible by removing many of the largest trees and moving some of the blocks back to their original positions; what exists today is a combination of the original fortification and the WPA restoration. In 2007, an additional $1 million in city funds was used to build a visitor's center.[5] More work on the site is planned.

References[edit]

- Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- ^ http://www.nashville.gov/Parks-and-Recreation/Historic-Sites/Fort-Negley/History.aspx

- ^ http://www.bonps.org/fort-negley/

- ^ http://www.nashville.gov/parks/docs/historic/ftnegley/NegleyTimeline.pdf

- ^ http://www.nashville.gov/Parks-and-Recreation/Historic-Sites/Fort-Negley/History.aspx

- ^ http://www.nashville.gov/parks/docs/historic/ftnegley/NegleyTimeline.pdf

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

External links[edit]

- Forts in Tennessee

- History of Nashville, Tennessee

- Museums in Nashville, Tennessee

- Works Progress Administration in Tennessee

- Buildings and structures in Nashville, Tennessee

- American Civil War museums in Tennessee

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Tennessee

- 1862 establishments in Tennessee

- National Register of Historic Places in Nashville, Tennessee

- American Civil War on the National Register of Historic Places