Americana, São Paulo

| Americana | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Saint Anthony Sanctuary, located in downtown Americana.

|

|||

|

|||

Location in the São Paulo state. |

|||

| Location in the São Paulo state. | |||

| Coordinates: 22°44′19″S 47°19′52″W / 22.73861°S 47.33111°WCoordinates: 22°44′19″S 47°19′52″W / 22.73861°S 47.33111°W | |||

| Country | |||

| Region | Southeast | ||

| State | São Paulo | ||

| Metropolitan Region | Campinas | ||

| Founded | 1875 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Omar Najar (PMDB) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 133.91 km2 (51.70 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 569 m (1,867 ft) | ||

| Population (2015) | |||

| • Total | 229,322 | ||

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,400/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Americanese | ||

| Time zone | BRT (UTC-3) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | BRST (UTC-2) | ||

| Postal code | 13465-000 | ||

| Area code(s) | (+55) 19 | ||

| HDI (2000) | 0.840 – high | ||

| Website | Americana website | ||

Americana (Portuguese pronunciation: [ameɾiˈkɐnɐ]) is a municipality (município) located in the Brazilian state of São Paulo. It is part of the Metropolitan Region of Campinas.[1] The population is 229,322 (2015 est.) in an area of 133.91 km².[2] The original settlement developed around the local railway station, founded in 1875, and the development of a cotton weaving factory in a nearby farm.

After 1866, several former Confederate citizens from the American Civil War settled in the region. Following the Civil War, slavery was abolished in the United States. In Brazil, however, slavery was still legal, making it a particularly attractive location to former Confederates, among whom was a former member of the Alabama State Senate, William Hutchinson Norris.[3]

Around three hundred of the Confederados are members of the Fraternidade Descendência Americana (Fraternity of American Descendants). They meet quarterly at the Campo Cemetery.[3]

The city was known as Vila dos Americanos ("Village of the Americans") until 1904, when it belonged to the city of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste. It became a district in 1924 and a municipality in 1953.

Americana has several museums and tourist attractions, including the Pedagogic Historical Museum and the Contemporary Art Museum.

Rio Branco Esporte Clube, founded in 1913, is the football (soccer) club of the city. The team plays their home matches at Estádio Décio Vitta, which has a maximum capacity of 15,000 people.

Contents

History[edit]

The first records on the occupation of the lands where Americana now stands date from the late 18th century, when Domingos da Costa Machado I acquired a crown property between the municipalities of Vila Nova da Constituição (now Piracicaba) and Vila de São Carlos (now Campinas). In that area several estates were created, including Salto Grande, Machadinho, and Palmeiras.

A part of the property, which included the Machadinho estate, was sold by Domingos da Costa Machado II to Antônio Bueno Rangel. After Rangel's death, the estate was divided between his sons José and Basílio Bueno Rangel. A part of the property was afterwards sold to the captain of the Brazilian National Guard, Ignácio Corrêa Pacheco, who is considered the founder of Americana.[4] [5] [6]

Immigration from the Southern United States[edit]

In 1866, the region started to be effectively populated with North-American immigrants from the defunct Confederate States of America, who were fleeing the aftermath of the American Civil War. The first immigrant to arrive was the lawyer and ex-state senator from Alabama, colonel William Hutchinson Norris. Norris installed himself in lands near the seat of the Machadinho estate and the Quilombo River.[3]

In 1867 the rest of his family arrived in Brazil, accompanied by other families from the Confederate States. These families settled in the region, bringing agricultural innovations and a kind of watermelon known as "Georgia's rattlesnake".

In 1875, almost a decade after the arrival of the Confederate immigrants in the region, the São Paulo Railways Company completed the expansion of its main railway to the city of Rio Claro. A station was built within the lands of the Machadinho estate. Despite belonging to the municipality of Campinas, the station was made to serve the estates in the municipality of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste, which was further away and had no station of its own.[3]

The inauguration of the station counted the Emperor Dom Pedro II and Gaston, comte d'Eu among those who attended. The station was baptized "Santa Bárbara station". It is unknown exactly when the small village became the city of Americana, but it is known that this village was created by the time of the inauguration of the railway station, and that it was Ignácio Corrêa Pacheco who distributed the lands. Pacheco is thus considered the founder of the city. The municipal holiday of Americana is still August 27, the day when the railway station was inaugurated.

The small town formed around the station was named "Villa da Estação de Santa Bárbara" (Santa Bárbara Station Town). Its inhabitants consisted mainly of American families, and the town became thus popularly known as "Villa dos Americanos" (Town of the Americans).[3]

The similarity between the official name of the town and the one of the neighboring municipality frequently caused serious communication problems, such as mail to Santa Bárbara Station often being shipped to the municipality of Santa Bárbara, ten kilometers away. In order to solve the problem, the railway company changed the name of the station in 1900 to "Estação de Villa Americana" (American Town Station). The name of the town itself was then also officially changed to "Villa Americana" (American Town).[4][5][6]

Carioba[edit]

In the 1890s, the farm known as Fazenda Salto Grande was purchased by the American Clement Willmot. Willmot established the first industry in Americana under the name Clement H. Willmot & Cia. In 1889, the factory was renamed Fábrica de Tecidos Carioba (Carioba Textile Factory). The name "Carioba" derives from the Tupi words for “white cloth”.

The factory ran into financial trouble after the abolition of slavery in 1888, and was purchased by German immigrants who were members of the Müller family. The town of Carioba sprang up around the factory. German immigrants brought European-style urbanization to Carioba which is reflected in the style of its manors, factories, hotels, and schools. Asphalt of tar was then first imported from Europe into Americana and utilized in road paving. The factory became the basis for the present-day Parque Industrial de Americana (Industrial Park of Americana).[4][5][6]

Italian immigration[edit]

On October 8, 1887, Joaquim Boer led a large group of Italian immigrants to Brazil. At Americana these Italian immigrants built their first church in 1896, dedicated to Saint Anthony of Padua, who eventually became the patron saint of the city. Born in Portugal, and called Saint Anthony of Lisbon there, the saint who is among the three June popular saints in the Catholic calendar (the others being Saints John the Baptist and Peter) is celebrated on June 13 with typical Junine countryside Brazilian food, prayers of the rosary, square dance, liquor, and bonfire.

Although immigrants got incentives to come to Brazil, especially after Emancipation when the government worried about seeing the country convert into a "black" nation, Italians who arrived before that didn't seem to have enjoyed special privileges. They often lived within the quarters designed for enslaved Africans who also suffered from lack of comfort and healthy conditions. Those immigrants worked as indentured servants, paying off their debts to farmers who had paid for their tickets and were exploited, until the system was revamped and improved. Their descendants went on to become laborers, merchants, and other professionals.[4][5][6]

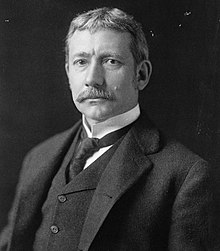

Elihu Root's visit[edit]

In 1906, two years after the creation of the Distrito de Paz de Villa Americana, the municipality received a visit from Elihu Root, United States Secretary of State, who had been attending and presiding the Pan-American Conference held in Rio de Janeiro. After the conference, Root visited other parts of Brazil (such as Araras), and was informed of the existence of Americana. Root expressed interest in visiting the town, and was received at Americana with great emotion and affection. Hundreds of the residents received Root at nighttime, and because there was no electricity residents carried torches. Root was touched by their reception.[citation needed]

Autonomy[edit]

With the change in status from village to district, Americana developed rapidly. Its first police force was created, a sub prefecture was established, and three street lights – lit by kerosene and brought from Germany – were introduced. A school was also established, with the sending of the educator Silvino José de Oliveira to represent Americana’s interests with the state government. All of these developments led the local inhabitants to clamor for the status of a city.

In 1922, Villa Americana was one of the most progressive districts in Campinas with a population of 4,500. In this year, the fight to change its status to city began, led by Antonio Lobo and others, such as Lieutenant Antas de Abreu, Cícero Jones and Hermann Müller himself. Their efforts finally bore fruit: on November 12, 1924, the Municipality of Villa Americana was created,[8] comprising two districts: Villa Americana and Nova Odessa, Nova Odesa later becoming its own municipality.

Constitutionalist Revolution and Economic Development[edit]

At the time of the beginning of the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship in Brazil in 1930, Americana was undergoing a profound economic transformation due to the rise of the textile industry there (the city was known as the “Rayon Capital”).

In 1932, during the administration of Mayor Antonio Zanaga, the revolt known as the Constitutionalist Revolution erupted against Vargas' regime. Americana sent volunteers to this revolution, and three of them, Jorge Jones, Fernando de Camargo and Aristeu Valente (from Nova Odessa, then part of Americana), perished during the struggle. Their sacrifice is remembered in Americana to this day.

In 1938, Mayor Zanaga changed the name of the town from Villa Americana to Americana, and due to the economic transformation of the town, the Comarca of Americana was created on December 31, 1953 during the administration of Mayor Jorge Arbix. In 1959, during the administration of Mayor Abrahim Abraham, Nova Odessa was made autonomous as its own municipality.[4][5][6]

Between 1960 and 1970, the rapid development of Americana caused many people to relocate to search for work. Because of its size, there was not enough room to accommodate the new residents and many lived on the border of Santa Bárbara d'Oeste and Americana, creating what is known today as "Zona Leste de Santa Bárbara" (East Santa Barbara).

The same also occurred because the majority of the population were unaware of the location where one municipality ended and where another began. The confusion came about because municipial limits were not yet fully determined. The problem was solved with the creation of a major Avenue, today called Avenida da Amizade (Friendship Avenue) which became the dividing line.

At the same time as these developments, some problems were also created. The sudden increase in population caused an unbalance in the public accounts of the municípality, which was not ready for such a great number of new residents.

Geography[edit]

Location[edit]

Americana is located in the center-east region of the state of São Paulo, Southeast Region.

- 124 km from São Paulo

- 205 km from the Port of Santos

- 35 km from Campinas

- 110 km from São Carlos

- 150 km from São Bernardo do Campo

- 30 km from Piracicaba

- 15 km from REPLAN em Paulínia

Climate[edit]

| This section does not cite any sources. (June 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Americana has a tropical climate, with hot summers and chilly winters. The median high temperature in summer is 84 °F (29 °C) and the median low is 64 °F (18 °C), comparable to Boston. In winter, the median high temperature is 72 °F (22 °C) and the median low temperature is 50 °F (10 °C), comparable to Orlando, Florida.

Demography[edit]

The population descends from a mixture of Luso-Brazilians (Luso meaning Portuguese) and immigrants, mainly Italian, Portuguese, German and Arabic. Because of its origins as a village settled by Confederate Southern US individuals, it received the name of "Americana", referring to "cidade" or city, the feminine form of "American", which in Portuguese means any native of the Americas, although often applied only to US nationals.[3]

Ethnic groups[edit]

- 84.6% White

- 12.0% Pardo (Brown)

- 2.4% Black

- 0.8% Asian

- 0.2% Amerindian

Culture[edit]

Theatres[edit]

- The Teatro Arena Elis Regina, or the Elis Regina Arena Theater (named after the greatest female Brazilian singer who died in 1980)was built in 1981 and became a venue for various artists. It was then abandoned to a state of dilapidation, having become a site of illegal activities. In 2000, reconstruction began, reopening on September 22, 2004. The theater was rebuilt with the idea of a circus in mind: it would offer various entertaining spectacles and activities simultaneously, and the theater was covered with a white canvas sheet, evoking the impression of lightness and brightness. The theater offers 1100 seats, two dressing rooms, and ample parking space.

- Teatro Municipal Lulu Benencasse, or Lulu Benencasse Municipal Theater, opened in 1986, occupying the building of the old Cine Brasil, which for decades had been a hang-out for young americanenses. Since its inauguration, it has served as the venue for various cultural offerings, such as plays, dance performances, and music, as well as different social and artistic programs. The theater was chosen as a film location by the producers of the film Por Trás do Pano (1999, with Denise Fraga) due to its traditional appearance. It has 840 seats.

Municipal Library[edit]

The Municipal Library, named after the teacher Jandira Basseto Pântano, was founded on October 25, 1955. It occupies the old building belonging to the Academic Group "Dr. Heitor Penteado" on Comendador Müller Square, near the Church of Santo Antônio. It contains 41429 books on various general subjects and 9051 children’s books, totalling 50,480 books (as of June 1999), as well as 114 various newspapers and 24,500 magazines, including children's. The average number of visitors in 1998 was 600 people, who mostly came in the afternoon. Its enrolled number of associates totals 31,900 people, as of December 1998.

Jandira Basseto Pântano was born on October 27, 1918 in Americana. She received her elementary education at the Escolas Reunidas, one of the first schools founded in the city. She completed her education at Campinas and in January 1938 was named a substitute teacher at the Academic Group "Dr. Heitor Penteado" before becoming a full-time teacher there. She worked as a teacher at the school for 22 years, and was noted for her hard work and diligence. She worked with all of the grades, but she preferred to work with the fourth year students, and prepare them for the wider world. She retired on March 9, 1968 and died on June 7, 1988. Up until her death, she continued to receive students at her home, helping illiterate adults and poor children.

Museums and cultural centers[edit]

- Museum of Contemporary Art (Museu de Arte Contemporânea (MAC)): Founded in 1978, it is found in a building attached to the Municipal Library. It contains 260 works of art by contemporary artists, including paintings, sculpture, engravings, designs, photographs, and artistic installations. The museum features exhibitions by local artists and by artists from other cities, as well as workshops and classes. It also contains a library and holds an annual national contest, which gives the "Prêmio Revelação de Artes Plásticas" (Revelation Prize of Plastic Arts) to young artists.

- "Conselheiro João Carrão" Historic and Pedagogical Museum (Museu Histórico e Pedagógico "Conselheiro João Carrão): This museum is located in the old farm known as Salto Grande built in colonial Minas Gerais style from taipa according to the “pilão” technique, where the material is piled and compressed into horizontal layers a course at a time, with foundations made from real wood. Located at the confluence of the Atibaia and Jaguari Rivers, the museum contains photographs, maps, historical artifacts and machines, furniture, and torture devices used during the slavery system.

Religion[edit]

- Roman Catholicism: Since the dismemberment of the Archdiocese of Campinas in 1976, Americana fell under the Catholic diocese of Limeira. Americana has a strong Catholic tradition due to the influence of Luso-Brazilians and of its Italian immigrants, who first began arriving in 1887. The first church at Americana was built in the middle of 1896 and dedicated to Saint Anthony of Padua, who became the patron saint of the city. The city has one of the largest Catholic churches in the country built in the Neoclassical style, the New Church of Saint Anthony (Matriz Nova de Santo Antônio), the largest in the diocese.[9]

- Protestantism and evangelicalism: Americana is also home to adherents of the Protestant, Pentecostal, and Neopentecostal faiths, such as the Nazarene, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Assembly of God, Adventist, Universal Church, and Jehovah's Witnesses. Immigrants from the Southern United States brought with them various customs and religions, mostly of the Presbyterian and Baptist persuasions.

Sports[edit]

In football the city is represented by Rio Branco Esporte Clube, founded on August 4, 1913. Rio Branco played in series A1 of the Campeonato Paulista since 1992 and was relegated to A2 in 2009.

It used to play in series C of the Campeonato Brasileiro. The team plays in Décio Vitta, with a capacity of 15,000.

Americana is also the hometown of Paralympics swimmer Danilo Binda Glasser, winner of two bronze medals in the Paralympics of Sydney 2000 and at Athens 2004, and footballer Oscar, a silver medallist at the 2012 London Olympics, a 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup champion, a 2011–2012 UEFA Champions League champion Chelsea F.C. player.[10]

In 2014, the city hosted the first Pan-American Korfball Championship.[11]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Região Metropolitana de Campinas

- ^ Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística

- ^ a b c d e f Gage, Leighton (8 January 2012). "Brazilian Confederacy". São Paulo, Brasil: Sleuthsayers. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e BIANCO, Jessyr Americana – Edição Histórica. Americana: Editora Focus, 1975

- ^ a b c d e Jolumá Brito, História de Campinas Vol XVIII

- ^ a b c d e Resumo Histórico - Prefeitura de Americana[permanent dead link]

- ^ [1] Conheça Americana.Símbolos do Município, retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Lei nº 1983 de 12 de novembro de 1924[permanent dead link]

- ^ Matéria no Jornal O Liberal sobre a Matriz Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ https://sports.yahoo.com/news/chelsea-midfielder-oscar-feels-huge-071200532--sow.html

- ^ IKF Pan-American Championships Archived November 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Americana, São Paulo. |

- (in Portuguese) Official website

- (in Portuguese) Flags of the World - Americana, São Paulo State (Brazil)