Bates College

|

|

| Latin: Academia Batesina | |

| Motto | Amore Ac Studio (Latin) |

|---|---|

|

Motto in English

|

With Ardor and Devotion by Charles Sumner |

| Type | Private |

| Established | March 16, 1855[note 1] |

| Endowment | $251.0 million (2016)[1] |

| Budget | $104.5 million (2016-17) |

| Chairman | Michael Bonney |

| President | Clayton Spencer |

|

Academic staff

|

190 (Winter 2017)[2] |

| Undergraduates | 1,780 (Winter 2017)[2] |

| Location | Lewiston, Maine, U.S. 44°6′20″N 70°12′15″W / 44.10556°N 70.20417°WCoordinates: 44°6′20″N 70°12′15″W / 44.10556°N 70.20417°W |

| Campus | Main campus: 133 acres (Rural) Bates Mountain: 600 acres (Mountainous) Coastal Center: 80 acres (Marine) Total holdings: 813 acres |

| Newspaper | The Bates Student |

| Colors | Garnet[3] |

| Athletics |

|

| Nickname | Bobcats |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | Bates.edu |

Bates College (![]() /ˈbeɪts/; Bates; officially the President and Trustees of Bates College)[4] is a private liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. It was founded by abolitionist statesmen and established with funds from industrialist and textile tycoon, Benjamin Bates. Bates is the oldest coeducational college in New England, the third oldest in the State of Maine, and the first to grant a degree to a woman in New England.

/ˈbeɪts/; Bates; officially the President and Trustees of Bates College)[4] is a private liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. It was founded by abolitionist statesmen and established with funds from industrialist and textile tycoon, Benjamin Bates. Bates is the oldest coeducational college in New England, the third oldest in the State of Maine, and the first to grant a degree to a woman in New England.

At its foundation in 1855 as the Maine State Seminary, it was one of the only colleges in the U.S. to admit black students before the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment. Its founder, Oren Burbank Cheney, established it as a Free Will Baptist institution, however, it has since secularized and established a liberal arts curriculum. Centered on the Historic Quad by two garnet gateways, the rural campus totals 813 acres (329 ha) with 33 Victorian Houses distributed throughout the city. It maintains a costal center of 80 acres (32 ha) on Atkins Bay and 600 acres (240 ha) of nature preserve known as the "Bates-Morse Mountain" near Campbell Island.[5]

It provides undergraduate instruction in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and engineering and offers joint undergraduate programs with Columbia University, Dartmouth College, and Washington University in St. Louis.[6] Unlike typical liberal arts colleges, the undergraduate program requires that all students complete a thesis before graduation, and has a substantiated research enterprise.[7] The Washington Post–a paper that aggregates American university rankings–places the undergraduate program as the 17th best in the country,[8] and as of August 2017, is the 12th best liberal arts college in the U.S. according to Forbes Magazine.[9]

Along with being the smallest in its athletic conference–the "NESCAC"–it competes as the Bates Bobcats against Colby and Bowdoin College in the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium. The Tier 1[10] athletic program has graduated 11 Olympians,[11] 209 All-Americans,[12] and currently maintains 32 varsity sports, some of which compete in Division I of the NCAA.

The students and alumni of Bates are well known for preserving a variety of strong campus traditions.[13][14][15] Bates alumni and affiliates include 86 Fulbright Scholars;[16] 22 Watson Fellows;[17] 5 Rhodes Scholars;[18] as well as 10 State Supreme Court Chief and Associate Justices; 10 members of the U.S. Congress; 7 Emmy Award winners; 5 Pulitzer Prize winners;[19] 3 U.S. Cabinet Secretaries;[20][21] and numerous CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, civil rights leaders, university presidents and U.S. State Legislators. The college is home to the Bates Dance Festival, the Mount David Summit, the Stephens Observatory, the Olin Arts Center and the Bates College Museum of Art (BCMoA).

Contents

History[edit]

Historical origins[edit]

While attending (and later leading) the Freewill Baptist Parsonsfield Seminary, Bates founder, Oren Burbank Cheney worked for racial and gender equality, religious freedom, and temperance.[22] In 1836, Cheney enrolled in Dartmouth College (after briefly attending Brown), due to Dartmouth's significant support of the abolitionist cause against slavery.[23] After graduating, Cheney was ordained a Baptist minister and began to establish himself as an educational and religious scholar.[24] Parsonsfield mysteriously burned down in 1854,[note 2] allegedly due to arson by opponents of abolition.[25][26] The event caused Cheney to advocate for the building of a new seminary in a more central part of Maine.[27]

With Cheney's influence in the state legislature, the Maine State Seminary was chartered in 1855 and implemented a liberal arts and theological curriculum, making the first coeducational college in New England.[28][29][30][31] Soon after establishment several donors stepped forward to finance portions of the school, such as Seth Hathorn, who donated the first library and academic building, which was renamed Hathorn Hall.[32] The Cobb Divinity School became affiliated with the college in 1866. Four years later in 1870, Bates sponsored a college preparatory school, called the Nichols Latin School.[33] The college was affected by the financial panic of the later 1850s and required additional funding to remain operational.[34] Cheney's impact in Maine was noted by Boston business magnate Benjamin Bates who developed an interest in the college. Bates gave $100,000 in personal donations and overall contributions valued at $250,000 to the college.[35][36] The school was renamed Bates College in his honor in 1863 and was chartered to offer a liberal arts curriculum beyond its original theological focus.[37] Two years later the college would graduate the first woman to receive a college degree in New England, Mary Mitchel.[38] The college began instruction with a six-person faculty tasked with the teaching of moral philosophy and the classics. From its inception, Bates College served as an alternative to a more traditional and historically conservative Bowdoin College.[39][40] There is a complex relationship between the two colleges, revolving around socioeconomic class, academic quality, and collegiate athletics.[41][42]

The college, under the direction of Cheney, rejected fraternities and sororities on grounds of unwarranted exclusivity.[43] He asked his close friend and U.S. Senator Charles Sumner to create a collegiate motto for Bates and he suggested the Latin phrase amore ac studio which he translated as "with love for learning" which has been taken as "with ardor and devotion,"[44] or "through zeal and study."[45] Prior to the start of the American Civil War, Bates graduated Brevet Major Holman Melcher, who served in the Union Army in the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He was the first person to charge down Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg.[46] The college graduated the last surviving Union general of the American Civil War, Aaron Daggett. The college's first African American student, Henry Chandler, graduated in 1874.[47] James Porter, one of General Custer's eleven officers killed at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 was also a Bates graduate. In 1884, the college graduated the first woman to argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, Ella Haskell.[48]

20th century[edit]

In 1894, George Colby Chase led Bates to increased national recognition,[49] and the college graduated one of the founding members of the Boston Red Sox, Harry Lord.[50][51] In 1920, the Bates Outing Club was founded and is one of the oldest collegiate outing clubs in the country,[52] the first at a private college to include both men and women from inception, and one of the few outing clubs that remains entirely student run.[53][54] The debate society of Bates College, the Brooks Quimby Debate Council, became the first college debate team in the United States to compete internationally, and is the oldest collegiate coeducational debate team in the United States.[55] In February 1920, the debate team defeated Harvard College during the national debate tournament held at Lewiston City Hall. In 1921, the college's debate team participated in the first intercontinental collegiate debate in history against the Oxford Union's debate team at the University of Oxford.[56] Oxford's first debate in the United States was against Bates in Lewiston, Maine, in September 1923.[57] In addition during this time, numerous academic buildings were constructed throughout the 1920s. During 1943, the V-12 Navy College Training Program was introduced at Bates. Bates maintained a considerable female student body and "did not suffer [lack in student enrollment due to military service involvement] as much as male-only institutions such as Bowdoin and Dartmouth."[55] During the war, a Victory Ship was named the S.S. Bates Victory, after the college.[58] It was during this time that future U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy enrolled along with hundreds of other sailor-students.[59][60][61] The rise of social inequality and elitism at Bates is most associated with the 1940s, with an increase in racial and socioeconomic homogeneity. Although Bates was founded as an egalitarian institution, the college began to garner a reputation for predominately educating white students who come from upper-middle-class to affluent backgrounds.[62] In the 1950s the college fenced off the campus in an attempt to "represent boundaries between Bates and Lewiston,"[63] to create a "symbolic separation between the purity of the Academia Batesina and underdeveloped city that surrounded them."[64] The New York Times detailed the atmopshere of the college in the 1960s with the following: "the prestigious Bates College — named for Benjamin E. Bates, whose riverfront mill on Canal Street in Lewiston was once Maine’s largest employer — provided an antithesis: a leafy oasis of privilege. In the 1960s, it was really difficult for most Bates students to integrate in the community because most of the people spoke French and lived a hard life."[65]

During this time the college began to compete athletically with Colby College, and in 1964, with Bowdoin created the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium. All three of the schools compete in the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC) and share one of the ten oldest football rivalries in the United States.[66][67] In 1967, President Thomas Hedley Reynolds promoted the idea of teacher-scholars at Bates and secured the construction of numerous academic and recreational buildings.[68] Most notably, Reynolds was integral to the acquisition of the Bates-Morse Mountain. Under Reynolds, Bates ceased being identified with any particular religion. Although never a sectarian college, Bates has historic ties to the Northern Freewill Baptist denomination whose members were instrumental in its founding. It maintained a nominal link to the Baptist tradition for 115 years. In 1970, that link ended when the college catalog no longer described Bates as a "Christian college." Bates College contributed to the movement to make standardized testing scores optional for college admission.

In 1984, Bates became one of the first liberal arts colleges to make the SAT and ACT optional in the admission process.[69] Reynolds began the Chase Regatta in 1988, which features the President's Cup that is contested by Bates, Colby, and Bowdoin annually. In 1989, Donald West Harward became president of Bates and greatly expanded the college's overall infrastructure by building 22 new academic, residential and athletic facilities, including Pettengill Hall, the Residential Village, and the Coastal Center at Shortridge.[70][71] During the 1990s (and mid 2000s), Bates consolidated its reputation of educating upper-middle-class to affluent Americans,[72][73][74] which lead to a student protests[75] and reforms to make the college more diverse both racially, and socioeconomically.[76]

21st century[edit]

Elaine Tuttle Hansen was elected as the first female president of Bates College[77][78] and managed the second largest capital campaign ever undertaken by Bates, totaling at $120 million and lead the endowment through the 2007-08 financial crisis. The college announced her retirement in 2011, appointing Nancy Cable as interim president, to serve through June 30, 2012, while the college conducted a national search for its eighth president. In 2011, Bates made national headlines for being named the most expensive university in the U.S.,[79][80] which caused backlash from American academia and students as it in-directly highlighted substantial socioeconomic inequality among students.[72][73] After a year-long search for the next president, Harvard University dean, Clayton Spencer, was appointed as Hansen's successor. Spencer assumed the presidency in 2012, and created diversity mandates, expanded student and faculty recruitment, and financial aid allocation.[81][82] While some reforms were successful, minorities at the college, typically classified as non-white and low income students, still reported lack of safe spaces, insensitive professors, financial insecurity, indirect racism and social elitism.[72][73] According to a 2017 article on income inequality by The New York Times,[83] 18% of Bates students came from the 1% of the American upper class (families who made about $525,000 or more per year),[84] with more than half coming from the top 5% (families who made about $110,000 or more per year).[85] In October 2016, the college announced the construction of new facilities, residential dorms (Chu and Kalperis Hall),[86] and the development new areas of study.[87]

According to the Portland Press Herald, Michael Bonney '80 and his wife donated $50 million to the college in support of the "Bates+You" fundraising campaign launched in May 2017. The campaign is the largest ever undertaken by the college totaling $300 million, with $168 million already raised as of May 2017.[88]

Academics[edit]

Bates College is a private baccalaureate liberal arts college that offers 36 departmental and interdisciplinary program majors and 25 secondary concentrations, and confers Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), Bachelor of Science (B.S.) and Bachelor of Science in Engineering (B.S.E.) degrees. Bates College enrolls 1,792 students, 200 of whom study abroad each semester.[89] The academic year is broken up into three terms, primary, secondary, and short term, also known as the 4–4–1 academic calendar. This includes two semesters, plus a Short Term consisting of five weeks in the Spring, in which only one class is taken and in-depth coursework is commonplace.[90] Two Short Terms are required for graduation, with a maximum of three.[90]

The largest social science academic department at Bates College is its Economics department, followed by Psychology, Politics, and History. The largest natural science academic department is the Biology department, followed by Mathematics, Physics, and Geology.[91] Bates offers a Liberal Arts-Engineering Dual Degree Program with Dartmouth College's Thayer School of Engineering, Columbia University's School of Engineering and Applied Science, and Washington University's School of Engineering and Applied Science. The program consists of three years at Bates and a followed two years at the school of engineering resulting in a degree from Bates and the school of engineering.[6]

Teaching and learning[edit]

Students at Bates take a first-year seminar, which provides a template for the rest of the four years at Bates. The student selects a specific topic offered by the college, and works together in a small class with a scholar-in-field professor of that topic, to study and critically analyze the subject. All first-year seminars place importance on writing ability, and composition in order to facilitate the process of complex and fluid ideas being put down on paper. Seminars range from constitutional analysis to mathematical theorizing. After three complete years at Bates, each student participates in a senior thesis or capstone that demonstrates expertise and overall knowledge of the Major, Minor or General Education Concentrations (GECs). The Senior Thesis is an intensive program that begins with the skills taught in the first-year program and concludes with a compiled thesis that stresses research and innovation.[92]

A feature of a Bates education is the Honors Program which includes a tutorial-based thesis modeled after the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.[93] The program consists of a senior thesis that is defended against a faculty panel. A faculty member must nominate the student for thesis candidacy by the conclusion of their junior year. Under the guidance of the nominating faculty member, the student declares his or her thesis(s) at the start of senior year and concludes it before his or her graduation. The thesis is subject to an oral examination, which is loosely based on defending a dissertation or oral argumentation. The oral examination committee includes a member of the faculty from a different department, and an examiner who specializes in the field of study the student is defending and is usually from another institution.[94]

Research and faculty[edit]

According to the U.S. National Science Foundation, the college received $1.15 million in grants, fellowships, and R&D stipends for research.[95] The college spent $1,584,000 in 2014 on research and development.[7] The Bates Student Research Fund was established for students completing independent research or capstones.[96] STEM grants are offered to students in the science, engineering, technology and mathematics fields who wish to showcase their research at professional conferences or national laboratories.[97][98][99] Independent research grants from the college can range from $300 to over $200,000 for a three-year research program depending on donor or agency.[100] The college's Harward Center is its main research entity for community-based research and offers fellowships to students.[101] According to a 2001 study, Bates College's economics department was the most cited liberal arts department in the United States.[102][103][104] The college's faculty were placed second in the country for their in-field research in 2007.[105]

Bates College has been the site of some important experiments and academic movements. In chemistry, the college has played an important role in shaping ideas about inorganic chemistry and is considered the birthplace of inorganic photochemistry as its early manifestations was started at the college by 1943 alumnus George Hammond who was later dubbed "the father of the movement".[106][107] Hammond would go on to invent Hammond's postulate, revolutionizing activation levels in chemical compounds.[108] In physics, 1974 alumnus Steven Girvin, credited his time at the college as pivotal in his development of the fractional quantum Hall effect, now a pillar in Hall conductance.[109][110] During the development and production of the first nuclear weapons during World War II, two students researching nuclear chemistry at the college were hired by the United States Army Corps of Engineers as part of the first Manhattan project scientific team.[111][112]

Atop the Carnegie Science Hall sits Stephens Observatory which houses the college's high-powered 12-inch Newtonian reflecting telescope. The telescope is used for research by the college, local government agencies, and other educational institutions. The Observatory is also home to an eight-inch Celestron, a six-inch Meade starfinder, and the only Coronado Solarmax II 60 in the state.[113][114][115]

As of 2017, Bates has a faculty of 190 and a student body of 1,780 creating a 10:1 student-faculty ratio and the average class size is about fifteen students. 100% of tenured faculty possess the highest degree in their field.[116] Full-time professors at the college received average total compensation of $123,066, with salaries and benefits varying field to field and position to position, putting faculty pay in the top 17% of all public and private universities.[117]

Bates College's faculty includes scholars such as political scientists Douglas I. Hodgkin, Stephen M. Engel, anthropologist Loring Danforth, historian Margaret Creighton, pianist and composer Thomas Snow, and author Steven Dillon.

Past faculty members of the college include: philosopher David A. Klob, historian Steve Hochstadt, ornithologist Jonathan Stanton, poet Fred D'Aguiar, English professor and first president of Reed College William Trufant Foster, U.S. Senator Porter H. Dale, economist Leonard Burman, visual artists William "Pope.L" Pope, musician Jody Diamond, and playwright Carolyn Gage.

Mount David Summit[edit]

The college holds the annual Mount David Summit which serves as a platform for students of all years to present undergraduate research, creative art, performance, and various other academic projects. Presentations at the summit include various dicispline-centered projects, themed panel discussions, films Q & A's, as well as other activities in the Lewiston area.[118] Started in 2002, the summit is held in Pettengill Hall, and on April 1, 2016, held its 15th summit.[119][120]

Admissions[edit]

Standards and selectivity[edit]

For the class of 2020, the college admitted 1,213 students out of 5,526 applicants. Bates accepted 18.3% of regular applicants and had an overall admit rate of 22%.[121] In the 2016 admissions rounds, all 170 transfer applicants failed to gain admission.[121] In 2015, the college had a 1.6% acceptance rate for waitlisted students.[122] U.S. News & World Report classifies Bates as "most selective",[123] and The Princeton Review designated it with a "selectivity rating" of 96 out of 99.[124]

The average high school GPA was an unweighted 3.71 and a weighted 4.06.[122] The average SAT Score was 2135 (715 Critical Reasoning, 711 Mathematics and 709 Writing), and the average ACT score range was 28 to 32.[91] Bates has a Test Optional Policy, which gives the applicant the choice to not send in their standardized test scores.[125] Bates' non-submitting students averaged only 0.05 points lower on their collegiate grade point average.[126]

Cost of attendance and financial aid[edit]

For the 2016-17 academic year, Bates charged a comprehensive price (tuition, room and board, and associated fees) of $66,550.[127] The college's tuition is the same for in-state and out-of-state students. Bates practices need-blind admission for students who are U.S. citizens, permanent residents, DACA status students, undocumented students, or who graduate from a high school within the United States, and meets all of demonstrated need for all admitted students, including admitted international students.[128] During the 2016-17 academic year the college dispensed $37.9 million in financial aid with $4.3 million to undocumented students.

Bates does not offer merit or athletic scholarships. Although Bates is often the most expensive school to attend in its athletic conference, the college covers 100% of financial need for students, and has an average financial package of $42,217. As of 2014, 44% of students utilize financial aid. Bates offers the Direct "+" Loan, Direct Student Loans, Pell Grants, Perkins Loan, Supplementary Educational Opportunity Grants (SEOG), and Work-Study Program.[129]

Demographics[edit]

For the class of 2019, the gender demographic of the college breaks down to 49% male and 51% female. 27% of U.S. students are students of color (domestic and international) and 13% of admitted students are first generation to college. The educational background for admitted students are mixed: 49% of students attended public schools and 51% attended private schools. About 90% of this incoming class (of those from schools that officially rank students) graduated in the top decile of their high school classes.[130][131] Bates has a 95% freshman retention rate. A significant portion of 45% of all applicants, transfer and non-transfer, are from New England.[91] About 89% of students are out-of-state, (all 50 states are represented), and the college has students from 73 countries.[132]

Rankings and reputation[edit]

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[133] | 35 |

| Liberal arts colleges | |

| U.S. News & World Report[134] | 23 |

| Washington Monthly[135] | 23 |

Bates is noted as one of the Little Ivies,[136] along with universities such as Bowdoin, Colby, Amherst, Middlebury, Swarthmore, Wesleyan, and Williams College. The college is also known as one of the Hidden Ivies, which includes much larger research universities such as John Hopkins and Stanford University. In 2016, Bates was ranked 23rd among all liberal arts colleges in the country by Washington Monthly. The peak position Bates has held on the Washington Monthly ranking was 6th in 2013.[137] Forbes ranked Bates 35th in its 2017 national rankings of 650 U.S. colleges, universities and service academies, putting the college the top 5% of institutions assessed. As a liberal arts college, Bates was ranked as the 12th best in the United States.[138]

| 2016 Princeton Review Rankings[139][140] | 6 |

| 351 Colleges for Great Food | 7 |

| Academic Experience | 12 |

| 2017 Forbes Financial Rankings[141] | |

|---|---|

| Forbes Financial Grade | A |

| 2016 Niche Rankings[142] | |

| Overall Niche Grade | A+ |

| 2016 Fulbright Rankings[143] | |

| Fulbright National Ranking | 3 |

| 2015 Alumni Ranker[144][145] | |

| Graduate Salaries (in Maine) | 1 |

| 2016-17 Pay Scale Rankings[146] | |

| Salary Potential, all universities | 13 |

| Salary Potential, Liberal Arts colleges | 3 |

For the 2016-17 academic year, Niche, formerly College Prowler, graded Bates with an overall grade of an 'A+'[147] noting an 'A+' for academics, 'A+' for campus food, 'A+' for technology, 'A' for administration, 'A-' for diversity, and an 'A' for campus quality.[148] As of 2015, Alumni Factor, which measures alumni success, ranks Bates first in Maine and among the top schools nationally.[144][145] In 2015, Bates produced 20 Bates students who received Fulbright fellowships, attaining the distinction of "Fulbright Top Producer", and subsequently breaking the college's previous record, and ranking Bates third in the United States.[143][149]

In 2003, U.S. News & World Report ranked Bates 8th in the nation for criteria in admissions and its selectivity.[140] The Fiske Guide to Colleges noted Bates as "highly selective and unconventional," later commenting that "Bates attracts many of the nation's brightest minds."[150] In 2005, the college was ranked first for 'Best Value in the United States' by The Princeton Review.[151]

In 2003, The Wall Street Journal, put Bates in the top 15% of all colleges and universities in the United States in percentage of students entering the top five graduate programs in Business, Law, and Medicine.[152] The college selected 10 colleges as its peers, namely Amherst, Bowdoin, Carleton, Yale, Williams, Wellesley, Middlebury, Pomona, Swarthmore, and Wesleyan.[153] The Peace Corps placed Bates 22nd, out of all liberal arts colleges, for international charity involvement.[154]

In 2017, according to The Washington Post–a paper that aggregates university rankings from six different publications–the undergraduate program is the 17th best in the United States.[8]

On September 20, 2016, PayScale released a report of 1,000 universities and their average graduate earning potential for the 2016-17 year. A Bates degree was worth approximately $120,000 in average salary making it the 13th highest among universities,[155] and the third highest among liberal arts in the U.S.[155]

Campus[edit]

Bates is located in a former mill town, Lewiston, which has a large French Canadian ethnic presence due to migration from Quebec in the 19th century. The college is known for cultural strains with the town, townspeople describing Bates as a "leafy oasis of privilege."[156] The overall architectural design of the college can be traced through the Colonial Revival architecture movement, and has distinctive Neoclassical, Georgian, Colonial, and Gothic features. The earliest buildings of the college were directly designed by Boston architect Gridley J.F. Bryant, and subsequent buildings follow his overall architectural template. Colonial restoration influence can be seen in the architecture of certain buildings, however many of the off campus houses' architecture was heavily influenced by the Victorian era.[157] Many buildings on campus share design parallels with Dartmouth College, University of Cambridge, Yale University, and Harvard University.[158][159]

Bates has a 133-acre main campus and maintains the 600-acre Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area,[160] as well as an 80-acre Coastal Center fresh water habitat at Shortridge.[161] The eastern campus is situated around Lake Andrews, where many residential halls are located. The quad of the campus connects academic buildings, athletics arenas, and residential halls. Bates College houses over 1 million volumes of articles, papers, subscriptions, audio/video items and government articles among all three libraries and all academic buildings. The George and Helen Ladd Library houses 620,000 catalogued volumes, 2,500 serial subscriptions and 27,000 audio/video items.[91] Coram Library houses almost 200,000 volumes of articles, subscriptions and audio/video items.[162] Approximately 150,000 volumes of texts, papers, and alumnus work are housed within academic buildings.

The most notable items in the library's collection include, copies of the original Constitution of Maine, personal correspondence of James K. Polk and Hannibal Hamlin, original academic papers of Henry Clay, personal documents of Edmund Muskie, original printings of newspaper articles written by James G. Blaine, and selected collections of other prominent religious, political and economic figures, both in Maine, and the United States.[163][164]

The campus provides 33 Victorian Houses, 9 residential halls, and one residential village.[91][165] The college maintains 12 academic buildings with Lane Hall serving as the administration building on campus. Lane Hall houses the offices of the President, Dean of the Faculty, Registrar, and Provost, among others.[166]

Olin Arts Center[edit]

The Olin Arts Center maintains three teaching sound proof studios, five class rooms, five seminar rooms, ten practice rooms with pianos, and a 300-seat grand recital hall. It holds the college's Steinway concert grand piano, Disklavier, William Dowd harpsichord, and their 18th century replica forte piano. The studios are modernized with computers, synthesizers, and various recording equipment.[167] The center houses the departments of Art and Music, and was given to Bates by the F. W. Olin Foundation in 1986.[168] The center has had numerous Artists in Residence, such as Frank Glazer, and Leyla McCalla.[169][170] The Olin Arts Center has joined with the Maine Music Society, to produces musical performances throughout Maine. In 2007, they hosted an event that garnered 260 musicians music recital inspired by Johannes Brahms.[171]

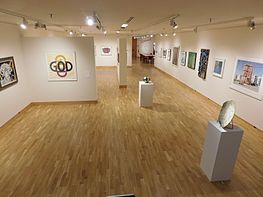

Museum of Art[edit]

Founded in 1955, the Bates College Museum of Art (MoA) holds contemporary and historic pieces. In the 1930s, the college secured a private holding from the Museum of Modern Art of Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night, for students participating in the 'Bates Plan'.[172] It holds 5,000 pieces and objects of contemporary domestic and international art. The museum holds over 100 original artworks, photographs and sketches from Marsden Hartley.[173][174][175] The MoA offers numerous lectures, artist symposiums, and workshops. The entire space is split into three components, the larger Upper Gallery, smaller Lower Gallery, and the Synergy Gallery which is primarily used for student exhibits and research. Almost 20,000 visitors are attracted to the MoA annually.[176]

Bates-Morse Mountain Area[edit]

This conservation area of 600 acres is available to Bates students for academic, extracurricular, and research purposes. This area is mainly salt marshes and coastal uplands. The college participates in preserving the plants, animals and natural ecosystems within this area as a part of their Community-Engaged Learning Program. Due to overall size, the site is frequently used by other Maine schools such as Bowdoin College for their Nordic Skiing practices.[177][178]

Coastal Center at Shortridge[edit]

This coastal center owned by Bates College, provides various academic programs, lectures, extracurricular activities, and research endeavors for students. 80 acres of wetlands, and woodlands with a fresh water pond, are available to numerous science departments and programs at Bates. There are two buildings on the land, a conference building, which can accommodate 15 people overnight, and a laboratory structured with an art studio on the upper floor. This area is also home to the Shortridge Summer Residency Program which provides students, faculty and researchers to work and study on the coastal land of Shortridge during the summer. Science majors and faculty work on site-based issues such as coastal changes, sea level fluctuations and public policy.[179]

Student life[edit]

The college's dining services have been featured on numerous national publications.[180] In 2015, the college's dining program was ranked 6th by The Princeton Review,[124] and 8th by Usatoday in the United States.[181] The college's dining services received the grade of 'A+' by Niche in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017.[147] The college holds one main dining area and offers two floors of seating. The college also institutes 'The Napkin Board' where students may leave comments or suggestions written on napkins for the dining program and its staff.[182] All meals and catered events on campus are served by Bates Dining Services, which makes a concentrated effort to purchase foods from suppliers and producers within the state of Maine, like Oakhurst Dairy and others.[183] The Den serves as an on-campus restaurant and is open until 1 AM Sun-Thurs. and 2 AM on Friday and Saturday nights.[184] While on campus, enrolled students and faculty have access to round-the-clock emergency medical services and security protection that only stops if the student or faculty leaves the physical campus or withdraws from the college.[185][186]

The college also holds an annual "Harvest Dinner" during Thanksgiving that features a school-wide dining experience including a New England buffet and live musical performances.[187][188] In 2015, shortly before the commencement of the Harvest Dinner, American rapper, T-Pain, performed.[189] Martin Luther King Day at Bates is celebrated annually with classes being canceled, and performances, events, keynote talks are held in observance. It is a day marked by keynotes from well known scholars who speak on the subjects of race, justice, and equality in America. In 2016, the college invited Jelani Cobb, to speak at the college on MLK Day.[190][191]

The college offers students 110 clubs and organizations on campus.[192] Among those is the competitive eating club, the Fat Cats, Ultimate Frisbee, and the Student Government.[192] The largest club is the Outing Club, which leads canoeing, kayaking, rafting, camping and backpacking trips throughout Maine.[193][194] Although Bates has since conception, rejected fraternities and sororities,[43] there are two secret societies that are unaffiliated with the college and discouraged by its administration.

Student media[edit]

The Bates Student[edit]

Bates College's oldest operating newspaper is The Bates Student, created in 1873. It is one of the oldest continuously published college weeklies in the United States, and the oldest co-ed college weekly in the country. Alumni of the student media programs at Bates have won the Pulitzer Prize,[195] and have their later work featured on major news sources.[196][197] It circulates approximately 1,900 copies around the campus and Lewiston area. Since 1990, there has been an electronic version of the newspaper online.[198] The newspaper provides access free of charge to a searchable database of articles stretching back to its inception on its website.

WRBC[edit]

WRBC is the college radio station of Bates College and was first aired in 1958. Originally started as an AM station at Bates, it began with the efforts of rhetoric professor and debate coach Brooks Quimby. It is ranked by The Princeton Review as the 12th best college radio station in the United States and Canada, making it the top college radio in the New England Small College Athletic Conference.[199]

A capella[edit]

There are five a cappella groups on campus. The Manic Optimists and the Deansmen are all-male, the Merminaders are all female and the coed groups are known as TakeNote and the Crosstones.[200] All groups have performed all over Maine and the Northeast.

Brooks Quimby Debate Council[edit]

Arguably the most well-known student organization at Bates is the Brooks Quimby Debate Council, due to endowment allocation, relative participation rate, awards and historical significance.[201] The formation of the team predates the establishment of the college itself as the debate society was founded within the Maine State Seminary making it the oldest coeducational college debate society in the United States. It was headed by Bates alumnus and teacher Brooks Quimby and became the first intercollegiate international debate team in the United States.[55] The Quimby Debate Society has been noted as "America's most prestigious debating society,"[202] and the "playground of the powerful."[203] During the 1930s, the debate society was subject to 'The Quimby Institute' which pitted each and every debate student against Brooks Quimby himself. This is where he began to engage heated debate with them that stressed "flawless assertions" and resulted in every error made by the student to be carefully scrutinized and teased.[55] Bates has an annual and traditional debate with Oxford, Cambridge and Dartmouth College. It competes in the American Parliamentary Debate Association domestically, and competes in the World Universities Debating Championships, internationally. As of 2013, the debate council was ranked 5th, nationally[204] and in 2012, the debate team was ranked 9th in the world.[205]

Traditions[edit]

Ivy Day[edit]

The class graduates participate in an Ivy Day which installs a granite placard onto one of the academic or residential buildings on campus. They serve as a symbol of the class and their respective history both academically and socially. Some classes donate to the college, in the form gates, facades, and door outlines, by inscribing or creating their own version of symbolic icons of the college's seal or other prominent insignia. This usually occurs on graduation day, but may occur on later dates with alumni returning to the campus. This tradition is shared with the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University. On Ivy Day, members of Phi Beta Kappa are announced.[13][14]

Winter Carnival[edit]

Nearly a century old, this tradition "celebrates cold and snowy weather, which is a trademark of fierce Maine winters".[15] The college has held, on odd to even years, a Winter Carnival which comprises a themed four-day event that includes performances, dances, and games. Past Winter Carnivals have included "a Swiss Olympic skier swooshing down Mount David", faculty and student football games, faculty and administration skits, oversized snow sculptures, "serenading of the dormitories", and an expeditions to Camden. When alumnus Edmund Muskie was governor, he participated in a torch relay from Augusta to Lewiston in celebration of the 1960 Winter Olympics.[206]

Robert F. Kennedy, with his naval classmates, built a replica of their boat back in Massachusetts out of snow in front of Smith Hall, during their carnival. This tradition is second only to Dartmouth College as the oldest of its kind in the United States.[55][207] Students are known to participate in what has been colloquially termed as the 'Dartmouth Challenge', which consists of alcohol related activities, closely related to that of parent ritual Newman Day, a tradition the college started in the 1970s.[42][208] The carnival has been hosted by the Bates Outing Club since its conception.[209]

Puddle Jump[edit]

On the Friday of Winter Carnival the Bates College Outing Club initiates the annual Puddle Jump. A hole is cut by a chainsaw or by the original axe used in the inaugural Puddle Jump of 1975, in Lake Andrews. Students from all class years jump into the hole, sometimes in costumes, to celebrate, "exuberance at the end of a hard winter." By mid-evening, they celebrate with donuts, cider and a cappella performances.[210]

Athletics[edit]

The college's official mascot is the bobcat, and official color is garnet. The college athletically competes in the NCAA Division III New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC), which also includes Amherst, Connecticut, Hamilton, Middlebury, Trinity, Tufts, Wesleyan, Williams, and Maine rivals Bowdoin and Colby in the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium (CBB). This is one of the oldest football rivalries in the United States. This consortium is a series of historically highly competitive football games ending in the championship game between the three schools. Bates is currently the holder of the winning streak, and has the record for biggest victory in the athletic conference with a 51-0 shutout of Colby College. Overall the college leads the Colby-Bates-Bowdoin Consortium in wins. Bates has won this championship at total of eleven times including 2014, 2015, and in 2016 won it again with a 24–7 win over Bowdoin, after their 21–19 home victory over Colby.[211][212]

According to U.S. Rowing, the Women's Rowing Team is ranked 1st in the New England Small College Athletic Conference, and 1st overall in NCAA Division III Rowing, as of 2016.[213] In the 2015 season, the women's rowing team was the most decorated rowing team in collegiate racing while also being the first to sweep every major rowing competition in its athletic conference in the history of NCAA Division III athletics. In 2015, the men's rowing team had the fastest ascension in rankings of any sport in its athletic conference and is currently the NESCAC Rowing Champion.[214] Bates has the 4th highest NESCAC title hold, is currently ranked 5th in its athletic conference and 15th in Division III athletics. As of 2016, the college has graduated a total of 11 Olympians, one of whom won the Olympic Gold Medal rowing for Canada at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.[11] The all-time leader of the Chase Regatta is Bates with a total of 14 composite wins, followed by Colby's 5 wins, concluding with Bowdoin's 2 wins.

The ice hockey team is the first team to win the NESCAC Club Ice Hockey Championships four times in a row.[215] As of 2016, the men's club ice hockey team is ranked 5th in the Northeast, and 25th overall in the NESCHA rankings.[216] In the winter of 2008, the college's Nordic Skiing team sent students that were was the highest ranked skiers in the Eastern Intercollegiate Ski Association and placed 4th in the 2008 NCAA Division I Championship.[217] In April 2005, the college's athletic program was ranked top 5% of national athletics programs.[218] The Men's Squash Team won the national championships in 2015, and 2016, with the winning student being the first in the history of the athletic conference, to be named the All American all four years he played for the college.[219] The men's track field is the first team in the history of Maine to have seven consecutive wins of the state championship, a feat completed in 2016.[220]

Bates maintains 31 varsity teams, and 9 club teams, including sailing, cycling, ice hockey, rugby, and water polo.[221]

Athletic facilities[edit]

Bates has athletic facilities that include:

- Alumni Gymnasium & Merrill Gymnasium

- Bates Squash Center & the Wallach Tennis Center

- Campus Avenue Field & Garcelon Field

- Clifton Daggett Gray Athletic Building & the Davis Fitness Center

- Leahey Baseball Pitch & the Lafayette Street Pitch

- 2,040 seat Underhill Arena Ice Rink

- Rowing Boathouse & Sailing Boathouse

- Russell Street Track

- 300 seat enclosed Tarbell Pool

Sustainability[edit]

In 2005, President Elaine Tuttle Hansen stated, "Bates will purchase its entire electricity supply from renewable energy sources in Maine" and secured a new contract, adding a premium of $76,000 to their energy supply.[222] Bates College signed onto the American College and University President's Climate Commitment in 2007.[223] In April 2008, the college completed its dining complex named "The Commons"[224] at a cost of approximately $24 million,[225] designed by the Japanese architectural firm Sasaki Associates.[226] The complex is 60,000 square feet, certified LEED Silver, and features occupancy sensors, anti-HCFC refrigerants, natural ventilation, heat islands, and five separate dining areas with almost 70% of the walls being glass paneling.[227]

In 2009, the college was given its third $5,000 grant allocation by the Hobart Center for Foodservice Sustainability which cited Bates as "having the best sustainability program among numerous entrants nationwide, which included K-12 schools and higher educational institutions, healthcare and hospitality facilities."[228] In 2010, the college was named one of 15 colleges in the United States to the "Green Honor Roll", by Princeton Review.[229] Bates currently mitigates 99% of emissions via electrical consumption and purchases all of its energy from Maine Renewable Resources. The college expended $1.1 million of its endowment to install lighting retrofits, occupancy sensors, motor system replacements and energy generating mechanisms. Select buildings at the college are open 24/7, thus requiring extra energy, due to this the college has implemented technology that places buildings on "stand-by" mode while minimum occupancy is attained to preserve energy. The practice is set to reduce the college's overall emissions levels by 5 to 10 percent. Overall, the academic buildings and residential halls are equipped with daylighting techniques, motion sensors, and efficient heating systems. Bates expended $1.5 million to implement a central plant that provides steam for heating for up to 80% of all on-campus establishments. The central plant is equipped with a modernized biomass systems and a miniature back-pressure steam turbine which reduces campus electricity consumption by 5%. The college also installed a $2.7 million 900kW hyper-roterized turbine that accounts for nearly one tenth of the campus' entire energy consumption.[230] Bates was the first food-service operation in higher education to join the Green Restaurant Association. In 2013, the environmental practices of the college's dining services were placed along with Harvard University, and Northeastern University, as the best in the United States by the Green Restaurant Association;[231] it earned three out of three stars, the only educational institution in Maine to do so.[232]

Bates maintains numerous environmental clubs and initiative such as Green Certification, which recognizes students who commit to sustainable policies and practices,[233] Green Bike, which offers students access to bicycles for use on and off campus for free,[234] and the Bates Action Energy Movement in which students participate in "both on-campus and nationwide environmental events and engage students with discussions on climate change and other pressing ecological crises."[235] The Bates College Museum of Art, offers programs such as the Green Horizons Program that showcase environmentalism in art, society, and culture.[236]

The United States Environmental Protection Agency honored Bates as a member of the Green Power Leadership Club due to the fact that 96% of energy used on campus is from renewable resources.[237] All newly developed buildings and facilities are built to LEED Silver and Gold standards.[238] The college is set to achieve complete carbon neutrality by 2020, as a result of campus-wide conservation efforts and specific initiatives in its implementation plan.[230]

Notable alumni[edit]

Bates alumni have included leaders in science, religion, politics, the Peace Corps, medicine, law, education, communications, and business; and acclaimed actors, architects, artists, astronauts, engineers, human rights activists, inventors, musicians, philanthropists, and writers. As of 2015, there are 24,000 Bates College alumni.[239] In 2016, two Bates alumni were featured on the Forbes' 30 Under 30 list.[240]

Business and finance[edit]

Alumni of Bates have yielded considerable influence in the worlds of business and finance. In 1860 the college graduated Albert Newman, who would go on to establish the largest dry goods corporation in the history of Kansas, Newman's Dry Goods Company. Three years later in 1863 the college graduated media magnate Daniel Collamore Heath who founded D. C. Heath and Company, which later became one of the first educational publishing firms in the United States, Houghton Mifflin. Bates has graduated various notable C-Level executives including the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of General Mills, Robert Kinney (1938),[241] Executive Chairman of Hannaford Brothers James Moody (1953),[242] Managing Director of the Fidelity Fund Barry Greenfield (1956),[243] CEO of AIM Broadcasting John Douglas (1960),[244] CEO of Central National Gottesman James Wallach (1964),[245] CEO of Playtex Rick Powers (1967), Chief Financial Officer (CFO) & Chief Operating Officer (COO) of Merrill Lynch Joseph Willit (1973),[246] CEO of Cedar Gate Technologies David B. Snow (1976),[247] CEO of Japonica Partners Paul Kazarian (1978),[248] Managing Director of RBC Capital Markets Robert E. Cramer[disambiguation needed] (1979), CEO of Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Michael Bonney (1980),[249] Vice-President of Microsoft Rick Thompson (1980),[250] CEO of the private equity fund for Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, L Catterton, Michael Chu (1980), Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) of L.L.Bean Stephen Fuller (1982),[251] President of the National Bank of Canada Louis Vachon (1983),[252] CEO of Easterly Darrell Crate (1989), Group Publisher of the Harvard Business Review Group Joshua Macht (1991), and financial commentator Michael Kitches (2000).[253]

Politics, military and legal studies[edit]

The alumni of Bates have also made a sizable impact in the worlds of government, military and law. Edmund Muskie graduated from the college in 1936, and subsequently became a State Representative, Governor of Maine, a U.S. Senator, and eventually the 58th United States Secretary of State. He ran with Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 Presidential Election against Richard Nixon and lost by a margin of less than 1%.[254] Robert F. Kennedy came to Bates in pursuit of the college's V-12 program and received a V-12 degree in 1944, subsequently becoming the United States Attorney General.[255][256] The college has graduated United States Representatives John Swasey (1859), Carroll Beedy (1903), Charles Clason (1911), Donald Partridge (1914), Frank Coffin (1940), Leo Ryan (1943), and in 1974 graduated the current Chairman of the Judiciary Committee Bob Goodlatte.[257]

During the American Civil War, Bates graduated many notable soldiers, commanders, and infantrymen. In 1862, the college graduated Holman Melcher,[258] who would go on to lead the defense of Little Round Top in the Battle of Gettysburg, become Mayor of Portland and famously be promoted to three different ranks during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House alone, being designated Brevet Major at its conclusion.[259] The college also graduated Medal of Honor recipients Frederick Hayes (1861), Josiah Chase (1861), Joseph F. Warren (1862), the oldest surviving Civil War General Aaron Daggett (1860), and the infamous Ku Klux Klan suppressor James Porter (1863);[260] for his service in the Korean War Lewis Millet (1943) also received the Medal of Honor.[261]

Bates graduated the first executive appointment by U.S. President Benjamin Harris and 2nd U.S. Minister to Columbia John Abbot in 1871, and in 1897 graduated the first Governor of Maine to be elected by a direct primary, Carl Milliken. In 1884, Bates graduated the first female lawyer in Montana, first female candidate for Montana Attorney General and the first women to argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court Ella Haskell. Prince Somayou of the Bassa tribe of West Africa Louis Penick Clinton graduated from the college in 1897. Civil rights leader, the 6th president of Morehouse College and personal mentor to Martin Luther King, Benjamin Mays graduated in 1920; he is the namesake of the college's Benjamin Mays Center.[262]

Bates has had a notable impact on the Maine Supreme Court in such that it has graduated three Chief Justices, Vincent McKusick (1943),[263] Albert Spear (1875), Scott Wilson (1892) and five Associate Justices, Enoch Foster (1860), Randolph Weatherbee (1932), David Nichols (1942), Louis Scolnick (1945), and Morton Brody (1955).

Academia and administration[edit]

The college has graduated many prominent members of academia and its administration. Ransom Dunn, class of 1840, became the first president of Hillsdale College and the fourth president of Rio Grande College. Founder of Harvard-Westlake School Grenville Emery graduated in 1868. Other notable administrators in academia include: President of University of Connecticut George Flint (1871), President of University of Colorado James Baker (1873), President of Rhode Island College and Johnson State College Walter Ranger (1879), President of Nichols College Gordon Cross (1931), President of Skidmore College Val Wilson (1938), President of Babson College William Rankin Dill (1951), Founder and President of Christendom College Warren Carroll (1953), President of Shaw University and Morgan State University King Virgil Cheek (1959). Robert Witt, graduated in 1962, served as the president of the University of Texas at Arlington, the University of Alabama, subsequently reaching the highest academic position of higher education in Alabama, the Chancellor of the University of Alabama System. Academic Richard Gelles (1968), is the current Dean of University of Pennsylvania's School of Social Policy and Practice. Economist Scott Bierman (1977), was elected the president of Beloit College in 2009. Valerie Smith (1975), Dean of the College at Princeton, was elected the third female and the first African American president of Swarthmore College.[264]

Arts and literature[edit]

Many Batesies have gone on to notable careers in the arts and literature. The first women to graduate from a New England college, Mary Mitchell (1869), became the Chair of English at Vassar College. Emmy Award-winning 15-year host of The Today Show, Bryant Gumbel graduated in 1970. Also graduating that year was John Shea, Emmy Award-winning actor and social activist.[265] Other notable writers and novelists include: Pulitzer and Emmy Award-winning author Elizabeth Strout (1977), and New York Times bestselling author Lisa Genova (1992).[266] The college has educated actors Jeffery Lynn (1930), Stacy Kabat, David Chokachi, Maria Bamford, and Cannes Film Festival-winning filmmaker Daniel Stedman (2001).[267][268] The current Editor-in-Chief of The Boston Globe, Brian McGrory graduated in 1984. Curator and historian Wanda Corn attended the school in 1962.[269]

Mathematics and sciences[edit]

Although a smaller school, the alumni of Bates have made a sizable impact in the world of mathematics and sciences. Frank Haven Hall graduated from the college in 1862, known as the "father of Braille", and is contested as the inventor of the first typewriter in the United States along with Christopher Latham Sholes. His inventions in Braille typewriters have been hailed as "the most innovative development of communications for the blind in the 19th century", and is known for his encounter with Hellen Keller at the Chicago World Fair.[42][270][271] Another prominent inventor is Steven Girvin, class of 1964, who invented the fractional quantum Hall effect.[272] Other notable scientists and mathematicians include: John Irwin Hutchinson (1889) who wrote Differential and Integral Calculus (1902) and the Elementary Treatise on the Calculus (1912),[273] biologist Herbert Walter (1892) who wrote the 1913 biology reflective series The Human Skeleton, Manhattan project scientists Frances Carroll (1939) and John Googin (1944), and the president of National Medical Association, John Kenney (1942). Chemist George Hammond graduated in 1943, he was member of the National Academy of Sciences, served as the executive chairman of the Allied Chemical Corporation for ten years and is known as the inventor of Hammond's postulate.[274]

Athletics[edit]

Alumni and associates of the college have also contributed to the world of athletics, sports management and professional sponsorships. Founding member of the Boston Red Sox, Harry Lord graduated in 1908, and played the very first baseball of the Red Sox two years after his graduation in 1911.[275][276] In 1927, the college graduated another member of the Red Sox, Charles Small, who pitched for the team for ten years. Frank Keaney graduated in 1911, and is credited as the inventor of baseball's fast break. Overall the college has graduated 11 Olympians, including: Emily Bamford, Hayley Johnson, Justin Freeman, Mike Ferry, Nancy Fiddler, Arnold Adams, Art Sager, Ray Buker, Harlan Holden, and Vaughn Blanchard. Andrew Byrnes, class of 2005, won the Olympic Gold Medal Rowing for the Canadian National Team.[277]

Alma mater[edit]

The college has many school songs; the college's Alma Mater was written by Irving Blake in 1911.[278]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Here's to Bates, our Alma Mater dear, Proudest and fairest of her peers;

We pledge to her our loyalty, Our faith and our honor thru the years.

Long may her praises resound. Long may her sons exalt her name.

May her glory shine while time endures, Here's to our Alma Mater's fame.

Administration[edit]

Leadership[edit]

Bates College is governed by its central administration, headquartered in and metonymically known as Lane Hall. The first president of the college was its founder, Oren Burbank Cheney and its current president is Clayton Spencer, who took office October 26, 2012.[279] She was previously a Dean at Harvard University reporting to the college's president. There have been eight presidents of Bates College, and one interim president.[280] The president is ex officio a member and president of the Board of Trustees, chief executive officer of the corporation, and principal academic of the college.[281]

There are currently 37 members on the Bates College Board of Trustees. The current Chairman of the Board is 1980 alumnus and former CEO of Cubist Pharmaceuticals, Michael Bonney.

Endowment and fundraising[edit]

Bates College is a tax-exempt organization that complies with section 501(c) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. According to NACUBO's "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Endowment Value Listing," the Bates College Endowment Fund has a mark-to-market value of $250.9 million as of the 2016 fiscal year. The endowment lost -4% from its 2015 value ($261.5 million) which in turn lost -0.8% from its 2014 value ($263.8 million) and currently holds a total of $358 million in capital investments.[1] As of 2015, the college has $541.8 million in assets under management (AUM).[282] This represents a +0.45% increase from the 2014 AUM value of $539.8 million. According to PwC, the net equity of Bates College is $2.1 billion as of 2015.[283]

As of the 2016 fiscal year, the college received $28.2 million in overall donations demonstrating a 134% increase in giving since 2013, and breaking the previous 2006 record of $24.8 million. In May 2017, Clayton Spencer announced the "Bates+You" fundraising campaign–the largest ever undertaken by the college–due to close out on $300 million.[284][285]

Although the college's endowment has seen increased growth and market value, it is considered high in its market but low among its peers; this increases the college's fee dependency and overall sticker price, which at one point was the most expensive in the country.[286][287] During the 2007-08 financial crisis and subsequent recession, the college's endowment lost 31% of market value.[288][289]

In 2014, members of the student advocacy group, Bates Energy Action Movement (BEAM), requested that the college divest from 200 companies that held the largest fossil fuel reserves.[290][291] In response the college asserted that the Board of Trustees had a fiduciary responsibility to the growth of the endowment and declined to specifically divest from the companies.[292] However, in accordance with the student's request the college did disclose its full investment strategy, and commented on the long term implications of divestment by saying:

Were we to guarantee a fossil fuel free endowment more broadly than the 200 companies, greater than half of the endowment would need to be liquidated. In either scenario, the transition would result in significant transaction costs, a long-term decrease in the endowment’s performance, an increase in the endowment’s risk profile, and thus a loss in annual operating income for the college.[293]

In fiction and literature[edit]

Throughout its history, the College has been notably featured in literature, artistic works and overall popular culture.

- The Sopranos (S1, E5): In the episode entitled, "College", Tony Soprano takes his daughter, Meadow on a trip to Maine to visit colleges that she is considering. They first visit Bates, while walking past the college's chapel she states, "[Bates College has] a 48-to-52 male-female ratio, which is great, strong liberal arts program and this cool olin arts center for music."[294] She later mentions the college's sexual atmosphere.[295]

- Ally McBeal (S1, E2): In the episode "Compromising Positions" it is revealed that Ally McBeal's brother is a fictional alumnus of Bates. Later in the episode Ally meets her first love interest of the series, Ronald, who is another fictional alumni of the college and was roommates with her brother.[296][297]

- The Letter (2003): Selected portions of the movie were filmed on or directly on the side of the college's campus.[298]

- 11.22.63 (novel) (2011): The protagonist of the Stephen King novel, Jacob Epping, is a fictional alumni of Bates.[299]

- The Simpsons (S27, E8):[300] In the episode entitled, "Paths of Glory", it is suggested to Lisa Simpson that she transfers to Bates.[301][302]

- 11.22.63 (S1, E5): In the episode entitled, "The Truth", Maine time-traveler Jake Epping (played by James Franco) tells his sweetheart that he went to Bates.[303]

- Lady Dynamite (2016): The Netflix original series is loosely based on the life of Bates alumni Maria Bamford. Bamford plays a fictionalized version of herself whose character also attended Bates.[304]

In media[edit]

- On April 20, 1987, actor Paul Newman wrote to President Reynolds to register his disapproval of one of the student's traditions called Newman Day.[305] The incident received widespread media coverage due to Newman's public disappointment with the tradition and the response of the college.[306][307]

- On July 17, 2006, Sports Illustrated profiled a tradition conceived by the students of Bates in an article entitled, "With This Ring, I Bust Thy Chops."[308]

- Bates has been subject to widespread media attention as one of the most expensive colleges in the United States and in June 2011, was named the most expensive in the United States.[79][286][309][310]

See also[edit]

- Nichols Latin School

- Parsonsfield Seminary

- List of colleges and universities in Maine

- Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence

- Liberal arts colleges in the United States

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b As of June 30, 2016. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2015 to FY 2016" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2017.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ Bates College

- ^ "Laws of the President and Trustees of Bates College" (PDF).

- ^ "Bates-Morse Mountain & Shortridge | Harward Center | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ a b "Pre-Law, Business, Engineering | Orientation | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ a b "NCSES Data Set".

- ^ a b "Here’s a new college ranking, based entirely on other college rankings". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- ^ Federle, Patrick. "Top 25 Liberal Arts Colleges 2017". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ^ "Best Academic D3 Schools" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Bobcat Olympians | Athletics | Bates College". athletics.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ^ "All-Americans | Athletics | Bates College". athletics.bates.edu. Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- ^ a b "The Class of 1975 joins the ivy stone tradition | News | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ^ a b Various. "The Bates Student".

- ^ a b "Colleges with Strong Winter Traditions | Bates College | Columbia University | Virginia Tech | Gettysburg College | Syracuse University". www.ivywise.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ^ "Bates graduate awarded Fulbright grant". Merit Pages. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ^ "Watson Fellowship - Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ^ http://www.rhodesscholar.org/docs/Institutions_for_Website_6_29_10.pdf

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize Winners". www.pulitzer.org. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ^ "Recent Bates Recipients Graduate Fellowships Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ^ "Recent Bates Recipients". abacus.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source; pp. 30.

...the bell tower flickered in flames while the children ran from its pillar-brick walls...screams awoke the night...

- ^ Cheney, Cheney, Emeline Stanley Aldrich Burlingame (1907). The Story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Boston, Mass., Pub. for Bates college by the Morning star publishing house. p. 24.

..Parsonfield Seminary burned down inexplicably...

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- ^ "Bates College | Best College | US News". colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

Bates College [is] the first coeducational college in New England.

- ^ "Bates College". Forbes. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

[Bates College] was the first coeducational college in New England.

- ^ "BatesNow | - | Faith by Their Works". 2010-03-28. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

...Because no colleges existed for women in New England...until Bates College was officially incorporated...

- ^ "Chapter 3 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ "The story of the life and work of Oren B. Cheney, founder and first president of Bates college". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source; pp. 2.

- ^ Larson, Timothy (2005). "Faith by Their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College from 1855 to 1877,". Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source.

- ^ "Oren B Cheney". Bates College. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Mary W. Mitchell | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ Calhoun, Charles C (1993). A Small College in Maine. Hubbard Hall, Bowdoin College: Bowdoin College. p. 163.

- ^ Eaton, Mabel (1930). General Catalogue of Bates College and Cobb Divinity School. Coram Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine.: Bates College. pp. 34, 36, 42.

- ^ "Chapter 4 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- ^ a b c Woz, Markus (2002). Traditionally Unconventional. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 6.

- ^ a b "Chapter 4 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ "Brand Identity Guide | Communications | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Chapter 1 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ Morgan, James. "Who Saves Little Round Top?".

Number four: Col. Chamberlain did not lead the charge. Lt. Holman Melcher was the first officer down the slope.

- ^ "Henry Chandler | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ "Progressive men of the state of Montana". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ "George C. Chase | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "A Brief History | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "Harry Lord | Society for American Baseball Research". sabr.org. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ "Student Clubs and Organizations | Campus Life | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "Bates Outing Club". Bates College. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "January 1920: The Outing Club's winter birth | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ a b c d e Clark, Charles E. (2005). Bates Through the Years: an Illustrated History. Edmund Muskie Archives: Bates College, Lewiston, Maine. p. 37.

- ^ "Bates debates Harvard at City Hall | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "Oxford and Bates to Meet in Debate". Google News Archives. Lewiston Daily Sun. 29 August 1923. p. 14. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ "Victory Ships by shipyard". www.usmm.org. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ^ "July 1943: The Navy arrives | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ Stuan, Thomas (2006). The Architecture of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 19.

- ^ Walter Isaacson (October 17, 2011). Profiles in Leadership: Historians on the Elusive Quality of Greatness. Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Larson, Timothy (2005). "Faith by Their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College from 1855 to 1877,". Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College Publishing. pp. Multi–source.

- ^ "Is the student-led Mount David cleanup a model for a litter-free hill?". 2016-06-13. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ^ Woz, Markus (2002). Traditionally Unconventional. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 6.

- ^ Araton, Harvey (2015-05-19). "The Night the Ali-Liston Fight Came to Lewiston". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ^ "NESCAC Member Institutions - NESCAC". www.nescac.com. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- ^ "Bowdoin Football Opens CBB Chase Saturday at Bates - Bowdoin". athletics.bowdoin.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- ^ "Thomas Hedley Reynolds | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "Optional Testing | Admission | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "Donald West Harward | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ "Donald W. Harward | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ a b c "Diversity of what? | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ a b c "Real talk | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ "Debunking the "Middle Class myth" | The Bates Student". www.thebatesstudent.com. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ "Bates College Students Protest Lack of Minorities". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 1994-04-13. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- ^ Shawker, Cheri (2016). "White Priviliage at Bates College". Bates College.

- ^ "Elaine Tuttle Hansen | Past Presidents | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ^ "Hansen inaugurated as Bates' seventh president | News | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- ^ a b "The 50 most expensive U.S. colleges". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ Staley, Oliver. "Bates Charging $51,300 Leads Expensive U.S. Colleges List". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ^ "Academic Access, Education Reform". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ "‘Questions Worth Asking’ — President Clayton Spencer's inaugural address | News | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ^ "Some Colleges Have More Students From the Top 1 Percent Than the Bottom 60. Find Yours.". The New York Times. 2017-01-18. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- ^ Thompson, Derek. "How Much Income Puts You in the 1 Percent if You're 30, 40, or 50?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- ^ Cox, Gregor Aisch, Larry Buchanan, Amanda; Quealy, Kevin (2017-01-18). "Economic diversity and student outcomes at Bates". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- ^ "Bates announces $10 million gift from Elizabeth Kalperis Chu ’80 and Michael Chu ’80 to name new residence halls". 2016-10-28. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ^ "Digital and Computational Studies | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ^ Writer, Noel K. GallagherStaff (2017-05-16). "Maine family gives $50 million ‘transformational’ gift to Bates College capital campaign - Portland Press Herald". Press Herald. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ^ "Academics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ a b "Short Term | Academics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ a b c d e "Bates College 2014/2015 Statistics and Facts" (PDF). Bates College. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ "Educating the Whole Person | Academics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- ^ "Honors Program - Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ^ "Honors Guidelines - Honors Program - Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ^ "NSF – NCSES Academic Institution Profiles – Bates College : Federal obligations for science and engineering, by agency and type of activity: 2014". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Bates Student Research Fund | Academics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "STEM Travel Grants | Academics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Barlow Grants | Off-Campus Study | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Research Opportunities | Academics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Grant News | External Grants | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Community-Engaged Research | Harward Center | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Economics department ranked at top of leading liberal arts college". Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Faculty | Economics | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "The Faculty Handbook of Bates College: Faculty Benefits and Support Programs". abacus.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-06.

- ^ "50 Colleges With the Best Professors - Best College Reviews". www.bestcollegereviews.org. Retrieved 2016-03-15.

- ^ Weiss, Richard G.; Wamser, Carl C. (2006). "Introduction to the Special Issue in honour of George Simms Hammond". Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. The Royal Society of Chemistry and Owner Societies (10): 869–870. doi:10.1039/b612175f. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Wamser, Carl C. (2003-05-01). "Biography of George S. Hammond". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 107 (18): 3149–3150. ISSN 1089-5639. doi:10.1021/jp030184e.

- ^ Fox and Whiteshell, Marye Anne and James K. (2004). Organic Chemistry. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 355–357. ISBN 0-7637-2197-2.

- ^ "Steven Girvin | Chair-Elect, Nominating Committee". American Physical Society. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ DiCarlo, L.; et al. (July 2009). "Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor". Nature. 460 (7252): 240–244. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..240D. PMID 19561592. arXiv:0903.2030

. doi:10.1038/nature08121. Retrieved 24 October 2010. arXiv

. doi:10.1038/nature08121. Retrieved 24 October 2010. arXiv - ^ Smith, D. Ray. "John Googin: The scientist of Y-12". Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Frances M. Carroll". Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ^ "Stephens Observatory | Physics & Astronomy | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ^ "The Ladd Planetarium | Physics & Astronomy | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-02.