Shwedagon Pagoda

| Shwedagon Pagoda | |

|---|---|

| ရွှေတိဂုံစေတီတော် | |

|

|

| Basic information | |

| Geographic coordinates | 16°47′54″N 96°08′59″E / 16.798354°N 96.149705°ECoordinates: 16°47′54″N 96°08′59″E / 16.798354°N 96.149705°E |

| Affiliation | Buddhism |

| Sect | Theravada Buddhism |

| Festival | Shwedagon Pagoda Festival (Tabaung) |

| Municipality | Yangon |

| Region | Yangon Region |

| Country | Myanmar |

| Status | active |

| Heritage designation | |

| Governing body | The Board of Trustees of Shwedagon Pagoda |

| Website | www |

| Completed | c. 6th century |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 105 m (344 ft) |

| Spire height | 112.17 m (368 ft) |

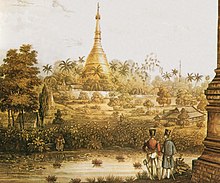

The Shwedagon Pagoda (Burmese: ရွှေတိဂုံဘုရား, IPA: [ʃwèdəɡòʊɴ pʰəjá]), officially named Shwedagon Zedi Daw (Burmese: ရွှေတိဂုံစေတီတော်, [ʃwèdəɡòʊɴ zèdìdɔ̀]) and also known as the Great Dagon Pagoda and the Golden Pagoda, is a gilded stupa located in Yangon, Myanmar. The 99-metre-tall (325 ft)[1] pagoda is situated on Singuttara Hill, to the west of Kandawgyi Lake, and dominates the Yangon skyline.

Shwedagon Pagoda is the most sacred Buddhist pagoda in Myanmar, as it is believed to contain relics of the four previous Buddhas of the present kalpa. These relics include the staff of Kakusandha, the water filter of Koṇāgamana, a piece of the robe of Kassapa, and eight strands of hair from the head of Gautama.[citation needed]

Contents

History[edit]

Historians and archaeologists maintain that the pagoda was built by the Mon people between the 6th and 10th centuries AD.[2] However, according to legend, the Shwedagon Pagoda was constructed more than 2,600 years ago, which would make it the oldest Buddhist stupa in the world.[3] According to tradition, Taphussa and Bhallika — two merchant brothers from the north of Singuttara Hill what is currently Yangon met the Lord Gautama Buddha during his lifetime and received eight of the Buddha's hairs. The brothers returned to Burma and, with the help of the local ruler, King Okkalapa, found Singuttara Hill, where relics of other Buddhas preceding Gautama Buddha had been enshrined.[citation needed] When the king opened the golden casket in which the brothers had carried the hairs, incredible things happened:

| “ | There was a tumult among men and spirits ... rays emitted by the Hairs penetrated up to the heavens above and down to hell ... the blind beheld objects ... the deaf heard sounds ... the dumb spoke distinctly ... the earth quaked ... the winds of the ocean blew ... Mount Meru shook ... lightning flashed ... gems rained down until they were knee deep ... all trees of the Himalayas, though not in season, bore blossoms and fruit.[4] | ” |

The stupa fell into disrepair until the 14th century, when King Binnya U (1323–1384) rebuilt it to a height of 18 m (59 ft). A century later, Queen Binnya Thau (1453–1472) raised its height to 40 m (131 ft). She terraced the hill on which it stands, paved the top terrace with flagstones, and assigned land and hereditary slaves for its maintenance. Binnya Thau yielded up the throne to her son-in-law Dhammazedi in 1472, retiring to Dagon. During her last illness she had her bed placed so that she could look upon the gilded dome of the stupa. The Mon face of the Shwedagon inscription catalogues a list of repairs beginning in 1436 and finishing during Dhammazedi's reign. By the beginning of the 16th century, Shwedagon Pagoda had become the most famous Buddhist pilgrimage site in Burma.[5]

A series of earthquakes during the following centuries caused damage. The worst damage was caused by a 1768 earthquake that brought down the top of the stupa, but King Hsinbyushin later raised it to its current height of 99 m (325 ft). A new crown umbrella was donated by King Mindon Min in 1871 after the annexation of Lower Burma by the British. An earthquake of moderate intensity in October 1970 put the shaft of the crown umbrella visibly out of alignment. A scaffold was erected and extensive repairs were made.

From 22 February 2012 to 7 March 2012, devotees celebrated the annual Shwedagon Pagoda Festival for the first time since 1988, when it was banned by the governing State Law and Order Restoration Council.[6][7] Celebrations began at the Rahu corner of the pagoda's yinbyin platform, at the Maha Pahtan and Aung Myay central platforms, at 9 am. on 22 February.[8] The Shwedagon Pagoda Festival, which is the largest pagoda festival in the country, begins during the new moon of the month of Tabaung in the traditional Burmese calendar and continues until the full moon.[7]

The pagoda is listed on the Yangon City Heritage List.

Design[edit]

The base of the stupa is made of bricks covered with gold plates. Above the base are terraces that only monks and other males can access. Next is the bell-shaped part of the stupa. Above that is the turban, then the inverted almsbowl, inverted and upright lotus petals, the banana bud and then the umbrella crown. The crown is tipped with 5,448 diamonds and 2,317 rubies. Immediately before the diamond bud is a flag-shaped vane. The very top—the diamond bud—is tipped with a 76 carat (15 g) diamond.[citation needed]

The gold seen on the stupa is made of genuine gold plates, covering the brick structure and attached by traditional rivets.[citation needed] People all over the country, as well as monarchs in its history, have donated gold to the pagoda to maintain it. The practice continues to this day after being started in the 15th century by the Queen Shin Sawbu (Binnya Thau), who gave her weight in gold.[citation needed]

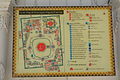

There are four entrances, each leading up a flight of steps to the platform on Singuttara Hill. A pair of giant leogryphs guards each entrance. The eastern and southern approaches have vendors selling books, good luck charms, images of the Buddha, candles, gold leaf, incense sticks, prayer flags, streamers, miniature umbrellas and flowers.

It is customary to circumnavigate Buddhist stupas in a clockwise direction. In accordance with this principle, one may begin at the eastern directional shrine, which houses a statue of Kakusandha, the first Buddha of the present kalpa. Next, at the southern directional shrine, is a statue of the second Buddha, Koṇāgamana. Next, at the western directional shrine, is that of the third Buddha, Kassapa. Finally, at the northern directional shrine, is that of the fourth Buddha, Gautama.[9]

Rituals[edit]

Most Burmese people are Theravada Buddhists, and many also follow practices which originated in Hindu astrology. Burmese astrology recognizes the seven planets of astrology — the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. In addition, it recognizes two other planets, Rahu and Ketu. All the Burmese names of the planets are borrowed from Hindu astrology, but the Burmese Rahu and Ketu are different from the Hindu Rahu and Ketu. The Burmese consider them to be distinct and separate planets, whereas Hindu astrology considers them to be either the Dragon's Head and Tails, or Ascending and Descending Nodes. To the Burmese people, Ketu is the king of all planets. As in many other languages, the Burmese name the seven days of their week after the seven planets, but Burmese astrology recognizes an eight-day week, with Wednesday being divided into two days; until 6 p.m. it is Wednesday, but after 6.pm. until midnight it is Rahu's day.[10]

It is important for Burmese Buddhists to know on which day of the week they were born, as this determines their planetary post. There are eight planetary posts, as Wednesday is split in two (a.m. and p.m.). They are marked by animals that represent the day — garuda for Sunday, tiger for Monday, lion for Tuesday, tusked elephant for Wednesday morning, tuskless elephant for Wednesday afternoon, mouse for Thursday, guinea pig for Friday and nāga for Saturday. Each planetary post has a Buddha image and devotees offer flowers and prayer flags and pour water on the image with a prayer and a wish. At the base of the post behind the image is a guardian angel, and underneath the image is the animal representing that particular day. The base of the stupa is octagonal and also surrounded by eight small shrines (one for each planetary post). It is customary to circumnavigate Buddhist stupas in a clockwise direction.

The pilgrim, on his way up the steps of the pagoda, buys flowers, candles, coloured flags and streamers. These are to be placed at the stupa in a symbolic act of giving, which is an important aspect of Buddhist teaching. There are donation boxes located in various places around the pagoda to receive voluntary offerings which may be given to the pagoda for general purposes. As of 2016 foreigners are charged an 8,000 Kyats (approx. 6 USD) entrance fee.

Shwedagon in literature[edit]

Rudyard Kipling described his 1889 visit to Shwedagon Pagoda ten years later in From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, Letters of Travel[11]

| “ | Then, a golden mystery upheaved itself on the horizon, a beautiful winking wonder that blazed in the sun, of a shape that was neither Muslim dome nor Hindu temple-spire. It stood upon a green knoll, and below it were lines of warehouses, sheds, and mills. Under what new god, thought I, are we irrepressible English sitting now? | ” |

| “ | 'There's the old Shway Dagon' (pronounced Dagone, not like the god in the Scriptures), said my companion. 'Confound it!' But it was not a thing to be sworn at. It explained in the first place why we took Rangoon, and in the second why we pushed on to see what more of rich or rare the land held. Up till that sight my uninstructed eyes could not see that the land differed much in appearance from the Sundarbans | ” |

War and invasion[edit]

In 1608 the Portuguese adventurer Filipe de Brito e Nicote, known as Nga Zinka to the Burmese, plundered the Shwedagon Pagoda. His men took the 300-ton Great Bell of Dhammazedi, donated in 1485 by King Dhammazedi. De Brito's intention was to melt the bell down to make cannons, but it fell into the Bago River when he was carrying it across. To this date, it has not been recovered.

Two centuries later, the British landed on May 11, 1824 during the First Anglo-Burmese War. They immediately seized and occupied the Shwedagon Pagoda and used it as a fortress until they left two years later. There was pillaging and vandalism, and one officer's excuse for digging a tunnel into the depths of the stupa was to find out if it could be used as a gunpowder magazine. The Maha Gandha (lit. great sweet sound) Bell, a 23-ton bronze bell cast in 1779 and donated by King Singu and popularly known as the Singu Min Bell, was carried off with the intention to ship it to Kolkata. It met the same fate as the Dhammazedi Bell and fell into the river. When the British failed in their attempts to recover it, the people offered to help provided it could be restored to the stupa. The British, thinking it would be in vain, agreed, upon which divers went in to tie hundreds of bamboo poles underneath the bell and floated it to the surface. There has been much confusion over this bell and the 42-ton Tharrawaddy Min Bell donated in 1841 by Tharrawaddy Min along with 20 kg of gold plating; this massive ornate bell hangs in its pavilion in the northeast corner of the stupa. A different but less plausible version of the account of the Singu Min Bell was given by Lt. J.E. Alexander in 1827.[12] This bell can be seen hung in another pavilion in the northwest of the pagoda platform.

The Second Anglo-Burmese War saw the British re-occupation of the Shwedagon in April 1852, only this time the stupa was to remain under their military control for 77 years, until 1929, although the people were given access to the Paya.

During the British occupation and fortification of the Pagoda, Lord Maung Htaw Lay, the most prominent Mon-Burmese in British Burma, successfully prevented the British Army from looting of the treasures; he eventually restored the Pagoda its former glory and status with the financial help from the British rulers. This extract is from the book “A Twentieth Century Burmese Matriarch” written by his great-great-great grand daughter Khin Thida.

| “ | After retirement he moved back to Rangoon area still in Burmese hands but very soon destined for the next annexation. He was again caught up in war but this time he had a great fortune of supporting religious ventures and gaining tremendous merit. His good karma and leadership abilities led him to the task of saving the great Shwedagon Pagoda from imminent destruction and sacking of its treasures by British troops in the second Anglo-Burmese War.

The great Buddhist shrine had been fortified by the British troops in the 1824 war and was again used as a fort in 1852. When he heard of the fortification and sacking of the shrine, he sent a letter of appeal directly to the British India Office in London stopping the desecration. He then obtained compensation from the British Commissioner of Burma Mr. Phayre and began the renovations of the Pagoda in 1855 with public support and donations. He became the founding trustee of the Shwedagon Pagoda Trust and he was awarded the title of KSM by the British Raj for his public service. He died at the age of 95, bequeathing his prestige and high repute to his large family and descendants. |

” |

Political arena[edit]

In 1920, students from Burma's only university met at a pavilion on the southwest corner of the Shwedagon pagoda and planned a protest strike against the new University Act which they believed would only benefit the elite and perpetuate colonial rule. This place is now commemorated by a memorial. The result of the ensuing University Boycott was the establishment of "national schools" financed and run by the Burmese people; this day has been commemorated as the Burmese National Day since. During the second university students strike in history of 1936, the terraces of the Shwedagon were again where the student strikers camped out.

In 1938, oilfield workers on strike hiked all the way from the oilfields of Chauk and Yenangyaung in central Burma to Rangoon to establish a strike camp at the Shwedagon Pagoda. This strike, supported by the public as well as students and came to be known as the '1300 Revolution' after the Burmese calendar year, was broken up by the police who, in their boots whereas Burmese would remove their shoes in pagoda precincts, raided the strike camps on the pagoda.

The "shoe question" on the pagoda has always been a sensitive issue to the Burmese people since colonial times. The Burmese people had always removed shoes at all Buddhist pagodas. Hiram Cox, the British envoy to the Burmese Court, in 1796, observed the tradition by not visiting the pagoda rather than take off his shoes. However, after the annexation of lower Burma, European visitors as well as troops posted at the pagoda openly flouted the tradition. U Dhammaloka publicly confronted a police officer over wearing shoes at the pagoda in 1902. It was not until 1919 that the British authorities finally issued a regulation prohibiting footwear in the precincts of the pagoda. However, they put in an exception that employees of the government on official business were allowed footwear. The regulation and its exception clause moved to stir up the people and played a role in the beginnings of the nationalist movement. Today, no footwear or socks are allowed on the pagoda.

In January 1946, General Aung San addressed a mass meeting at the stupa, demanding "independence now" from the British with a thinly veiled threat of a general strike and uprising. Forty-two years later, on August 26, 1988, his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi addressed another mass meeting of 500,000 people at the stupa, demanding democracy from the military regime and calling the 8888 Uprising the second struggle for independence.

September 2007 protests[edit]

In September 2007, during nationwide demonstrations against the military regime and its recently enacted price increases, protesting monks were denied access to the pagoda for several days before the government finally relented and permitted them in.

On September 24, 2007, 20,000 bhikkhus and thilashins (the largest protest in 20 years) marched at the Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon. On Monday, 30,000 people led by 15,000 monks marched from Shwedagon Pagoda and past the offices of Aung San Suu Kyi's opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party. Comedian Zarganar and star Kyaw Thu brought food and water to the monks. On Saturday, monks marched to greet Aung San Suu Kyi, who is under house arrest. On Sunday, about 150 nuns joined the marchers.[13][14] On September 25, 2007, 2,000 monks and supporters defied threats from Myanmar's junta. They marched to Yangon streets at Shwedagon Pagoda amid army trucks and the warning of Brigadier-General Myint Maung not to violate Buddhist "rules and regulations."[15]

On September 26, 2007, clashes between security forces and thousands of protesters led by Buddhist monks in Myanmar have left at least five protesters dead by Myanmar security forces, according to opposition reports,[citation needed] in an anticipated crackdown. Earlier in the day security authorities used tear gas, warning shots and force to break up a peaceful demonstration by scores of monks gathered around the Shwedagon Pagoda.

The web site reports that protesting "monks were beaten and bundled into waiting army trucks," adding about 50 monks were arrested and taken to undisclosed locations. In addition, the opposition said "soldiers with assault rifles have sealed off sacred Buddhist monasteries ... as well as other flashpoints of anti-government protests." It reports that the violent crackdown came as about 100 monks defied a ban by venturing into a cordoned-off area around the Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar's holiest Buddhist shrine.

It says that authorities ordered the crowd to disperse, but witnesses said the monks sat down and began praying, defying the military government's ban on public assembly. Security forces at the pagoda "struck out at demonstrators" and attacked "several hundred other monks and supporters," the opposition web site detailed. Monks were ushered away by authorities and loaded into waiting trucks while several hundred onlookers watched, witnesses said.[citation needed] Some managed to escape and headed towards the Sule Pagoda, a Buddhist monument and landmark located in Yangon's city centre.

Replicas[edit]

Uppatasanti Pagoda—located in Naypyidaw, the capital of Myanmar—is a replica of Shwedagon Pagoda. Completed in 2009, it is similar in many aspects to Shwedagon Pagoda, but its height is 30 cm (12 in) less than that of Shwedagon.[16]

Another replica of Shwedagon Pagoda, 46.8 m (154 ft) in height, was constructed at Lumbini Natural Park in Berastagi, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Completed in 2010, the construction materials for this pagoda, were imported from Myanmar.[17]

Global Vipassana Pagoda, 29 m (95 ft) high and opened in 2009, located in Mumbai, India [18]

Gallery[edit]

-

Devotees paying homage to the Triple Gem

-

The Singu Min Bell

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Shwedagon Pagoda Architecture". shwedagonpagoda.com. The Board of Trustees of Shwedagon Pagoda. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ Pe Maung Tin (1934). "The Shwe Dagon Pagoda". Journal of the Burma Research Society: 1–91.

- ^ Hmannan Yazawin. Royal Historical Commission of Burma. 1832.

- ^ Reed, Robert; Grosberg, Michael (2005). Myanmar (Burma). Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1740596954.

- ^ BURMA, D. G . E. HALL, M.A., D.LIT., F.R.HIST.S.Professor Emeritus of the University of London and formerly Professor of History in the University of Rangoon, Burma.Third edition 1960. Page 35-36

- ^ Gecker, Jocelyn (22 February 2012). "Festival returns to Myanmar's Shwedagon Pagoda". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Banned festival resumed at Shwedagon Pagoda". Mizzima News. 22 February 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ Eleven News (in Burmese). 23 February 2012 http://www.weeklyeleven.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=12475:2012-02-22-19-17-28&catid=43:2009-11-10-07-39-09&Itemid=111. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Billinge, T (2014). "Shwedagon Paya". The Temple Trail. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Skidmore, Monique. Burma At The Turn Of The Twenty-first Century. University of Hawaii Press, 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Kipling, JR (1914). "II: The River of the Lost Footsteps and the Golden Mystery upon its Banks. Shows how a Man may go to the Shway Dagon Pagoda and see it not and to the Pegu Club and hear too much. A Dissertation on Mixed Drinks". From sea to sea and other sketches: letters of travel. Volume I. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ Bird, GW (1897). Wanderings in Burma (1st ed.). London: F.J. Bright and Son.

- ^ Afp.google.com, 30,000 rally as Myanmar monks' protest gathers steam

- ^ Radionz.co.nz, Monks continue to pile pressure on military

- ^ Matthew Weaver. "Troops sent in as Burmese protesters defy junta". the Guardian.

- ^ Roughneen, S (2013-11-13). "Naypyidaw’s Synthetic Shwedagon Shimmers, but in Solitude". The Irrawaddy. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Irrawaddy Publishing Group. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Taman Alam Lumbini International Buddhist Center (2010-11-01). "The Inauguration Ceremony of Shwedagon Pagoda Replica". Shwedagon's Pagoda Replica Project. Berastagi, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ "Global Vipassana Pagoda inaugurated in Mumbai". DNA. 8 February 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

Further reading[edit]

- Martin, Steve (2002). Lonely Planet Myanmar (Burma). Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 1-74059-190-9.

- Elliot, Mark (2003). South-East Asia: The Graphic Guide. Trailblazer Publications. ISBN 1-873756-67-4.

- Win Pe (1972). Shwedagon. Printing and Publishing Corporation, Rangoon.

- "Dictionary of Buddhism" by Damien Keown (Oxford University Press, 2003) ISBN 0-19-860560-9

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shwedagon pagoda. |

- Official website

- Official Website of the Shwedagon Pagoda for the Shwedagon Pagoda Board of Trustees

- The Legend of Shwedagon by Khin Myo Chit

- My Child-life in Burmah by Olive Jennie Bixby 1880 recollections of a missionary's daughter : inc. detailed description of King Mindon's new hti being erected, pp 111

- Rudyard Kipling's description of Shwedagon Pagoda in 1889

- Elizabeth Moore conference the shwedagon in british burma myanmar

- Lt. J.E. Alexander's account, 1827, p. 153

- Myanmar: Time to say hello YouTube

- "Scene upon the Terrace of the Great Dagon Pagoda" from 1826