Utah State Capitol

| Utah State Capitol | |

|---|---|

The Capitol looking northwest

|

|

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical Revival, Corinthian style |

| Location | Capitol Hill, Salt Lake City, Utah, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°46′38″N 111°53′17″W / 40.77722°N 111.88806°WCoordinates: 40°46′38″N 111°53′17″W / 40.77722°N 111.88806°W |

| Construction started | December 26, 1912 |

| Inaugurated | October 9, 1916 |

| Renovated | 2004–2008 |

| Cost | $2.7 million |

| Renovation cost | $260 million |

| Owner | State of Utah |

| Height | 285 ft (87 m) (dome) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 5 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Richard K.A. Kletting |

| Website | |

|

Capitol Building

|

|

| NRHP reference # | 78002667[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 11, 1978 |

The Utah State Capitol is the house of government for the U.S. state of Utah. The building houses the chambers and offices of the Utah State Legislature, the offices of the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, the State Auditor and their staffs. The capitol is the main building of the Utah State Capitol Complex, which is located on Capitol Hill, overlooking downtown Salt Lake City.

The Neoclassical revival, Corinthian style building was designed by architect Richard K.A. Kletting, and built between 1912 and 1916. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Beginning in 2004, the capitol underwent a major restoration and renovation project. The project added two new buildings to the complex, while restoring many of the capitol's public spaces to their original appearance. One of the largest projects during the renovation was the addition of a base isolation system which will allow the building to survive as much as a 7.3 magnitude earthquake. After completion of the renovations, the building was rededicated and resumed normal operation in January 2008.

Contents

Early Houses of Government[edit]

The first Euro-American settlers arrived in what would become Utah on July 24, 1847, which is now commemorated as Pioneer Day in the state. These settlers, Mormon pioneers led by Brigham Young, appealed to the United States Congress for statehood in 1849, asking to become the State of Deseret. Their proposal was denied, but they received some recognition in September 1850 when the U.S. Government created the Territory of Utah as part of the compromise of 1850.[2] A territorial assembly, known as the Utah Territorial Legislature, was created to be the governing body for the territory. The assembly met in various buildings including the Council House, which had originally been constructed to serve as capitol of the provisional State of Deseret, until the first capitol building was constructed.[3]

One of the first official acts of the assembly was to designate a capital city for the territory. On October 4, 1851, Millard County and its capital of Fillmore were created in the empty Pavant Valley for this purpose. The area was named for then current president Millard Fillmore. Its centralized location in the territory made it seem an ideal place for Utah's capital city.[4] Construction started on Utah's first capitol building, known as the Utah Territorial Statehouse, the next year. The building was designed by LDS Church Architect Truman O. Angell, and was funded with $20,000 (equivalent to $9.36 million in 2016[5]) appropriated by the United States Congress.[3] The $20,000 was insufficient to pay for the capitol as designed, and so only the south wing was completed. In December 1855, the fifth Utah Territorial Legislature met in the building (it would be the first and only complete session in Fillmore). The next year the sixth Utah Territorial Legislature once again met in the statehouse, but the session was relocated to Salt Lake City after legislators complained about the lack of housing and adequate facilities in Fillmore. As a result, in December 1856 Salt Lake City was designated Utah's capital, and the statehouse in Fillmore was abandoned.[4] Several buildings in Salt Lake City then served as temporary homes for the state legislature and offices for state officers, including the previously used Council House, and beginning in 1866, the Salt Lake City Council Hall.

History of the Capitol[edit]

Early attempts for a capitol building[edit]

As time passed, those smaller buildings became inadequate, so several local leaders and businessmen began to call for a new permanent capitol building. Several of these people requested that Salt Lake City donate about 20 acres (81,000 m2) of land, specifically an area known as Arsenal Hill, just north of the intersection of State and Second North Streets. The City Council of Salt Lake responded by approving a resolution on March 1, 1888, donating the property to the territorial government. A "Capitol Commission" was created to review the design and construction process for the new building. The commission selected Elijah E. Myers, who also designed the Michigan, Texas, and Colorado State Capitols, to design Utah's building. The plans were finished by 1891, but were ultimately rejected because of the $1 million (equivalent to $238 million in 2016[5]) cost estimated. Plans for a capitol building were then delayed after the approval of an Enabling Act allowing Utahns to begin plans for statehood.[3] On January 4, 1896 Utah was granted statehood, and the Salt Lake City and County Building was used as a capitol building for the new state.

The design and planning process[edit]

By 1909 no capitol had yet been constructed and Governor William Spry, recognizing that Utah was one of only a few states without a capitol building, sent a proposal to the state legislature asking for the creation of a new commission to oversee the construction of a capitol. During that year's legislative session the commission was created and efforts made to gain funding for construction. An appropriation bill, which would use a one mill property tax, was produced but failed in a required popular vote that June. Funding options in the form of bonds and loans were also researched.[6] In 1910 the state constitution was amended to allow bonding for the capitol building, and by 1911 a bill authorizing $1,305,000 (equivalent to $205 million in 2016[5]) in bonds was presented to the state legislature. The bill passed both houses after the amount was reduced to $1 million (equivalent to $157 million in 2016[5])and was signed into law by the governor in Spring 1911.[3] Funds were also boosted when Union Pacific Railroad president, Edward Henry Harriman, died in 1909, and his widow was required to pay a five-percent inheritance tax to the state of Utah. Union Pacific had helped to construct the Transcontinental Railroad, which was completed in Utah, and Harriman had invested $3.5 million in Salt Lake City's electric trolley system. Because of these investments within the state, Mrs. Harriman paid the state treasurer $798,546 (equivalent to $124 million in 2016[5]) on March 1, 1911, as required by law.[6]

After funding was secured, the commission began the design process for the building and grounds. The Olmsted Brothers of Massachusetts were chosen to provide the landscaping design and site plan. As options for the site on Capitol Hill were researched several members of various committees expressed concerns with the proposed site, due mainly to the cost of grading the steep hillside. In December 1911, a three-person committee was organized to consider other locations for a capitol building. One of the more popular sites considered was located on Fort Douglas property, near the present University of Utah, while others proposed locating the building in downtown Salt Lake City near the City and County Building. In the end, it was decided to construct on the original 20 acres (81,000 m2) site known as Capitol Hill, and attempt to acquire surrounding property for the capitol campus. Aware of the demand for their properties, several owners charged the state exorbitant prices for the property needed to complete the site.[3]

Even as questions arose concerning the site location, and work progressed on site plans, the design of the building was begun. The commission decided to hold a design competition, a practice common for many public buildings of that era. A program for the competition was created with design requirements such as required square footage, the desired number of floors, and stipulation to keep the total cost under $2 million (equivalent to $311 million in 2016[5]). The program was approved August 30, 1911, and information was sent to architectural firms. Those which were interested responded, and the commission selected 24 firms to compete. Because the compensation was less than expected, several contenders withdrew from the competition, and the commission further reduced the list to eight firms. The final designs for the building were due on January 12, 1912, less than five months after the finalists were selected. After designs were submitted the commission met several times to discuss their selections, and some architects were asked to make presentations. After two months the commission reduced the list of designs to just two, those submitted by Richard K.A. Kletting and Young & Sons, both of Salt Lake City.[3] On March 13, 1912 the commission made its final vote and selected Richard Kletting's design by a vote of four to three.[7] After his appointment as capitol architect, Kletting traveled to several capitols in the eastern United States, including the Kentucky State Capitol which influenced his final designs. His first working plans for the building were due July 15, 1912.

Construction[edit]

After Kletting produced more detailed plans, they were made available to contractors interested in bidding to work on the capitol. The submitted bids were opened December 3, 1912 at Salt Lake's Commercial Club with James Stewart & Company receiving the contract as general contractor on December 19, 1912. P. J. Morgan was awarded the contract for excavation and grading the site, and the capitol's groundbreaking ceremony took place December 26, 1912. A large amount of soil had to be excavated from the hill side, as the eastern side of the site was as high as the building's planned fourth story. The excavation was done using a steam shovel which dug into the hillside filling its large dipper, after which it turned around and emptied the dirt into a temporary Dinkey train. The small train then carried the soil to the nearby City Creek Canyon where it was dumped.[3] After the building's base was graded and excavated, work on the foundation started. The capitol was to be built of stone, with a concrete and steel superstructure.

By spring 1913 the foundation and basements walls were in place, and the steel columns and wooden frames for the concrete were being installed. Numerous small shops and offices had been constructed on the hill surrounding the site to support the building efforts, along with numerous small railroad lines carrying stone, mixed concrete, and other supplies. Contractors leased a right-of-way up Little Cottonwood Canyon, which originally held a railroad track from mines at Alta, and constructed a new railroad to carry granite from the canyon's quarry to the capitol site. On April 4, 1914, Governor William Spry presided over the cornerstone-laying ceremony. The cornerstone, dated 1914, was laid at the top of the southern steps, and was filled with records and photographs documenting the building's construction and Utah's culture.[8]

By the end of summer 1914 the basement, second floor, and exterior walls were nearing completion. The columns were being installed, and work progressed on the dome, including covering it in Utah copper. The capitol commission urged the work forward, hoping the eleventh session of the Legislature would be able to meet in the building the following year. But, as 1914 ended, work had not progressed enough and when the legislature met the next year, it did so in the Salt Lake City and County Building, until February 11, 1915, when the session was moved into the new capitol. Even though the legislature was meeting in the capitol, it took more than a year to finish the remainder of the building sufficiently for the executive and judicial officers to occupy the building. After work was finished the capitol was publicly dedicated on October 9, 1916. The original construction cost was $2,739,538.00 (equivalent to $320 million in 2016[5]) and replacement cost is estimated at $310,000,000 (equivalent to $36.2 billion in 2016[5]). The capitol was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.[1] It is included in the Capitol Hill Historic District, a historic district also listed on the National Register.[1]

Later alterations[edit]

Since its completion in 1916, the capitol has had numerous alterations, all varying in scale.

Renovation and restoration[edit]

In summer 2004 the capitol closed for an extensive renovation, which included restoration work and a seismic upgrade. The renovation was guided by three main goals, first strengthen the structure to withstand as much as a 7.3 magnitude earthquake, then restore the original architectural and artistic details of the building, all while retaining functionality after the renovation.[9] On August 7, 2004, the day before the capitol closed, a "Capitol Discovery Day" was held, and the public was invited to visit the capitol and learn about the changes being made, and why the project was necessary.[10] By August 8, the day the capitol closed, the renovation had already begun in certain locations around Capitol Hill. In 2002, following the 2002 Winter Olympics, some buildings added to the capitol campus, such as the circular cafeteria building, were demolished, and construction started on two new buildings. These two buildings, constructed north of the capitol, would serve as temporary offices during the structure's restoration.[11] Much of the asbestos on the exterior of the building (used to waterproof the dome) had been removed that summer by inmates from the Utah State Prison, working in the Utah Correctional Industries program.[12]

Some of the major improvements made during the renovation included updating or replacing the heating, cooling, plumbing, and electrical systems. Many rooms in the structure were restored to their original size, having been divided into smaller rooms over time; while others, like the Senate Chamber, were enlarged. Rooms were repainted their original colors, and new carpets, matching the 1916 originals, were installed. The 550 original windows had been replaced with aluminum trimmed ones in the early 1960s, and during the restoration they were replaced with replicated mahogany-trimmed, energy efficient, and in some areas bulletproof, windows. Original furniture was restored, and new period furniture was purchased. The floor of the rotunda had originally included glass, which allowed light to pass from the skylights down to the first floor, and the glass was restored during the renovations.[13]

One area which received much attention was the building's dome. The dome's drum, or circular base, experienced water leakage for many years. Contrary to architect Kletting's design, the state had used stucco and plaster, versus terra cotta, to give the appearance of stone on the exterior of the dome. Over time, the plaster deteriorated and allowed water penetration that damaged the interior murals.[13] In an effort to stop this the state had coated the drum area with a coating made of asbestos. During the restoration, the asbestos was removed, and actual terra cotta replaced the leaking plaster and stucco. In the dome's interior structure, a cathodic protection system was installed to prevent any further damage to the concrete and steel. The system uses a network of electrical anodes to induce a small electric current into the steel, altering the electrolytic cycle and slowing the corrosion process. To help increase the dome's strength, a new six-inch shot concrete wall was applied over the existing concrete inside the dome's structure.[14]

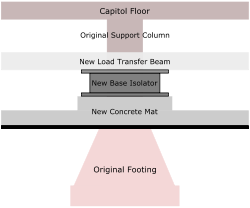

Arguably the largest part of the renovation was improving the building's resistance to earthquake damage. A base isolation system was installed under the building to provide this protection. The building's isolation system is composed of a network of 280 base isolators, each 20 inches (51 cm) high, and between 36 inches (91 cm) and 44 inches (110 cm) in diameter. Installing the isolators required excavating the dirt around and beneath the capitol, exposing the foundation and footings. The original concrete support columns were then attached to a network of new load transfer beams, which extended horizontally from under the building, and were supported by pile caps under and along the perimeter of the capitol. The support columns were then detached from the original footings, leaving the building sitting on the load transfer beams and pile caps. A new concrete mat was poured around and on top of the original footings, leaving a space between the new load transfer beams and the concrete mat. The base isolators were then installed on top of the concrete mat, directly above the covered footings. Once all the isolators had been installed the temporary supports between the pile caps and load transfer beams were removed, leaving the beams to sit directly on the isolators, which sit on the concrete mat foundation. The isolators are made of layers of laminated rubber, and are very strong vertically but not horizontally, which allows the building to rock gently back and forth as the ground underneath moves during an earthquake.[14]

Several other improvements during the renovation will help to improve the building's stability, including the addition of concrete shear walls within the structure. The shear walls will keep the building from twisting or distorting, which could cause a collapse as it moves during an earthquake. The shear walls were installed in empty vent shafts left from the original construction, and inside new elevator shafts and stairwells. The granite columns along the structure's exterior were also in danger of buckling during a seismic event, and as a result the joints were injected with an epoxy adhesive during the renovation work.[14]

The innovative restoration and upgrade was the first of its kind on such a large scale. The final cost was $260 million (equivalent to $322 million in 2016[5]) which did not include the construction of two additional legislative office buildings on the capitol campus at a cost of $37 million each (equivalent to $45.8 million in 2016[5]).[15] The capitol was rededicated on January 4, 2008, and opened to the public the next day. Funds dedicated to the capitol complex make it the costliest state capitol complex in the United States.[citation needed]

Architecture[edit]

Exterior[edit]

The capitol's architecture was inspired by Classical architecture, and some local newspapers compared the early designs to Greece's Parthenon. Many of the building's details rely on the Corinthian style, in which formality, order, proportion and line are essential design elements. The building is 404 feet (123 m) feet long, 240 feet (73 m) feet wide, and the dome is 250 feet (76 m) high.[16]

The exterior is constructed of Utah granite (Quartz monzonite mined in nearby Little Cottonwood Canyon), as are other Salt Lake City landmarks such as the Salt Lake Temple and LDS Conference Center. The stone facade is symmetrical, with each side being organized around a central pedimented entrance. Fifty-two Corinthian columns, each 32 feet (9.8 m) tall by 3.5 feet (1.1 m) in diameter sitting on an exposed foundation podium, surround around the south (front), east and west sides of the capitol.[3]

Interior[edit]

The building's interior has five floors (four main floors and a basement). The capitol is decorated with many paintings and sculptures depicting Utah's history and heritage, including statues of Brigham Young, first territorial governor, and Philo T. Farnsworth, Utah native and a developer of television. The floors are made of marble from Georgia.

Basement[edit]

The basement has been heavily remodeled throughout the years, and much of the eastern half of the basement has been replaced by the base isolators (which are meant to make the building more resistant to earthquakes). Because of the slope of the ground under the building the western half of the capitol still contains a full basement, with base isolators underneath. During the 2004-2008 restoration a terrace was constructed which surrounds the building on the east, west, and south sides; this terrace extended the basement level beyond the original walls. Today the basement houses maintenance and security offices, mechanical and storage space, several conference and meeting rooms, the Legislative Printing Office, Bill Room, and a fitness center. The Capitol Hill Association, a group of political lobbyists, also rents space in the basement for a lounge.[17]

First floor[edit]

The first floor, or ground floor, was the first completed and has the least amount of decorative finish work. The exterior stairs on the east and west ends of the building lead to this level, versus the front steps which lead directly to the second floor. When first completed in 1916 the ground floor was mostly a vast, open exhibit space spanning the entire length of the building, while offices were built in the four corners of this level. The ceiling beneath the rotunda above is made of glass (which also serves as the floor above), and allows light from the 2nd floor to illuminate the ground floor also. Over time the large open areas of the ground floor were walled in and divided, extending the offices into the public space.[18] Now the ground floor still contains many of the capitol's exhibits, and includes a small visitor center and gift shop.

Second floor[edit]

The building's second floor, often referred to as the main floor, has retained much of its historic appearance over the years. This floor also serves as the first level of the three-story rotunda and flanking atria. The rotunda occupies the center of the building, under the dome. The interior ceiling of the dome, which reaches 165 feet (50 m) above the floor, includes a large painting by artist William Slater. The mural includes seagulls flying amongst clouds, and was choose because the California gull is Utah's official state bird and represents the Miracle of the gulls from Utah's history. Also within the dome is a cyclorama, with eight scenes from Utah's history, including the driving of the Golden Spike and the naming of Ensign Peak; the characters in the scenes of the cyclorama stand approximately 10 feet (3.0 m) high. When the capitol was opened in 1916 the cyclorama was blank, and was not painted until the 1930s, as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project.[19]

The dome is supported by marble covered, coffered arches, which sit on four pendatives.[18] The coffered arches each depict a scene from Utah's history including the exploration of Utah by John C. Frémont, the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition, the fur trapping done by Peter Skene Ogden and lastly the arrival of the Mormons Pioneers led by Brigham Young. At the bottom of the pendatives surrounding the rotunda are niches containing statues. The niches are original to the building, but until the restoration they remained empty. Prior to the renovations, three artists, Eugene L. Daub, Robert Firmin, and Jonah Hendrickson were commissioned to create statues to fill them. The four statues, each approximately 11 feet (3.4 m) tall and known collectively as "The Great Utahs" represent Science and Technology, Land and Community, Immigration and Settlement, along with the Arts and Education.[19] Suspended from the dome's ceiling is the original chandelier weighing 3,000 lb (1,400 kg) (The chain supporting it weighs an additional 1,000 lb (450 kg)). The chandelier is an exact copy of one hanging in the Arkansas State Capitol, and during the restoration process Arkansas sent several, period glass diffusers to Utah to replace broken ones found in its chandelier.[20]

Flanking the east and west sides of the rotunda are atria, which contain large skylights, allowing sunlight to enter the public areas. Surrounding the atria are two levels of balconies which are supported by twenty-four monolithic, Ionic style columns.[18] At the end of each atriim is a marble staircase, and a mural. The arched mural on the west end, above the entrance to the House Chamber is entitled the Passing of the Wagons, while the mural at east end, above the entrance to the Supreme Court, is known as the Madonna of the Wagon. Both murals were meant as a tribute to the early pioneers, and were the first commissioned works of art in the capitol, being signed by Girard Hale and Gilbert White.[19]

The state reception room, or gold room, is also located on this floor, and is often used to entertain visiting dignitaries. The gold room gets its name from the extensive usage of gold leaf in its decoration. The ceiling contains a painting entitled Children at Play by New York artist Lewis Schettle. The majority of finishings and furniture in the room have been imported from Europe, including the Russian walnut table, and several chairs are upholstered with Queen Elizabeth's coronation fabric.[19] Just west of the gold room, is the Governor's office.

Third floor[edit]

The third floor, also known as the legislative floor, contains the chambers for both the House and Senate, along with the Supreme Court. When the building was first completed the north-east corner of this floor contained the library, which has since been relocated, and the area divided into smaller offices.[18] At the end of the west atrium area is the entrance to the House of Representatives. The House is composed of 75 members, who serve two-year terms, and represent approximately 29,000 citizens each.[21] During the restoration the House chamber was restored to the original paint colors and period carpets. Two 103 in (260 cm) plasma display screens were installed at the front of the chamber for voting processes and presentations, a first of its kind system in a state capitol.[19] New desks were created, based on the originals, but now allow room for modern technology such as printers and computers.[19] The ceiling of the chamber is a large skylight, allowing natural light to illuminate the room. The chamber also features four murals painted on the rounded ceiling coves, two of which (east and west) are original to the buildings, while the other two were painted during the renovation. The east mural, entitled The Dream of Brigham Young was painted by New York artist, Vincent Aderente, and shows Young standing near the Salt Lake Temple and holding their blueprints. The east mural, entitled Discovery of the Great Salt Lake, shows Brigham Young conversing with Jim Bridger about the Great Salt Lake, and is the work of A. E. Foringer. The north mural features Utah resident, Seraph Young, voting in Utah's first election following the granting of women's suffrage in the territory. The south mural features the Engen brothers building their first Ski jump, representing the importance of outdoor recreation to the economy of Utah.[19] The House Lounge, located directly behind the chamber, was restored to its original size and configuration, and furnished with period carpets and furniture.

The Senate chamber, which houses the Utah State Senate, is located in the northern part of the center wing. The Senate is composed of 29 members, who serve for terms of four-years. Senators sit facing north, towards the speaker. The chamber was expanded during the renovation, removing the walls on each side, opening what were hallways to the floor of the chamber. Like the House's chamber, the Senate Chamber was restored with original paint colors and period furniture. Included within the chamber are three murals, the first is original to the building, and was painted across the entire, upper-part, of the front wall. The mural, known as a polyptych, is a landscape by A.B. Wright and Lee Greene Richards showing Utah Lake, located a 45-minute drive south of the capitol, in Utah County. During the restoration, two new paintings, by Logan artist Keith Bond were painted. The eastern mural, entitled Orchards along the Foothills, shows the Wasatch Mountains of Northern Utah. The western mural, entitled Ancestral Home shows an Anasazi ruin amongst the red-rock hills of Southern Utah.[19]

The Supreme Court chamber is located at the far east end of building. The chamber is currently only used for ceremonial purposes as the Utah Supreme Court relocated to the Scott M. Matheson Courthouse in downtown Salt Lake City in 1998.

Fourth floor[edit]

Both historically and after its renovation, the fourth floor contains the viewing galleries for both the house and senate chambers, along with several offices and committee rooms. Much of the floor is open to floors below, allowing visitors to look down on the third or second floors in several locations. When the capitol opened, this floor was also used as an art gallery, and currently it contains several small exhibits along with a statue of Philo Farnsworth, a developer of television and a Utah native.

Grounds and Capitol Complex[edit]

The capitol building is the centerpiece of a 40-acre (160,000 m2) plot which also includes a Vietnam War memorial, Utah Law Enforcement Memorial, and a monument dedicated to the Mormon Battalion. The renovations added a new plaza, a reflecting pool, and two office buildings, as well as underground parking.[22] The grounds feature plants, shrubs, and trees native to Utah, as well as good views of Salt Lake City, the Salt Lake Valley and the Wasatch Front.

Other buildings[edit]

State Office Building[edit]

By the 1950s the capitol was reaching capacity, and there was little room to expand offices in the building without making drastic changes to the historical layout. As a result, the state legislature appropriated $3 million (equivalent to $87 million in 2016[5]) to construct a new office building, located about 350 feet (110 m) directly north of the capitol. A new master plan was also created during the design process which specified creating a new plaza which would connect the two buildings and cover a new underground parking facility. The other parking lots in the complex were expanded and a maintenance shop was constructed for state vehicles. The new plan also set aside space for the construction of two more office buildings on the east and west sides of the plaza. The new building was designed by Scott & Beecher Architecture, and was smaller than the capitol building but contained much more usable working space. The finished plans were completed and presented to the state during November 1958.[3]

Construction of the new building started with a groundbreaking ceremony held March 8, 1959. Because the new plan required a large amount of excavation work, the removed dirt was used to build up the ground for Interstate 15, also under construction during that period. After the building was completed, it was dedicated on June 9, 1961.[3]

In popular culture[edit]

In Legally Blonde 2: Red, White and Blonde (2003) the Utah State Capitol was used for exterior and interior pictures of the U.S. Capitol. In Drive Me Crazy (1999), the Centennial prom scene was filmed in the Capitol Rotunda.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c National Park Service (April 15, 2008). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ^ Lyman, Edward Leo (1994). "Statehood for Utah". In Powell, Allan Kent. Utah History Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874804256. OCLC 30473917.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cooper/Rogers Architects (September 13, 2000). "Chapter II". Building & Grounds Restoration Master Plan and Historic Structures Report (PDF). Capitol Preservation Board. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Ison, Yvette D. (July 1995). "Utah's First Territorial Capitol, Fillmore, Was Too Remote for Legislators". History Blazer. Utah History To Go. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k United States nominal Gross Domestic Product per capita figures follow the Measuring Worth series supplied in Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2017). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved July 28, 2017. These are the figures as of 2016.

- ^ a b Cooley, Everett L. (July 1959). "Utah's Capitols" (PDF). Utah Historical Quarterly. Utah Historical Society. 27 (3): 263. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Utah Capitol Resembling Parthenon, Will Be Built by Utah Architect". The Salt Lake Evening Telegram. March 14, 1912. Retrieved September 12, 2013 – via Utah Digital Newspapers.

- ^ "Capitol Cornerstone Will Be Laid Today". The Salt Lake Evening Telegram. April 4, 1914. Retrieved September 12, 2013 – via Utah Digital Newspapers.

- ^ Warburton, Nicole (January 3, 2008). "Capitol Redux: Historic Building's Renovation Complete". Deseret News. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Erickson, Tiffany (August 10, 2004). "Thousands Bid Capitol Farewell Before 4-Year Renovation Starts". Deseret News. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Nielson-Stowell, Amelia (August 1, 2004). "Designs More Inviting to Public". Deseret News. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Genessy, Jody (August 10, 2004). "'Chain Gang' Working at the Capitol". Deseret News. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Utah Division of State History. "The Utah State Capitol: Then and Now". Utah Division of State History. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Jerod G. (2005). "Modern Solutions to Historic Problems: The Utah State Capitol Building Seismic Retrofit Project" (PDF). Utah Preservation. Utah State Historical Society. 9: 52–56. ISSN 1525-0849.

- ^ "Utah State Capitol Seismic Retrofit and Restoration" (PDF). Parsons Corporation. December 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Architect of the Capitol. "The United States Capitol Dome". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ Gehrke, Robert (January 25, 2010). "Lobbyists Set Up in New Capitol Quarters". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Cooper/Rogers Architects (September 13, 2000). "III". Building & Grounds Restoration Master Plan and Historic Structures Report (PDF). Capitol Preservation Board. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h State of Utah (2008). "Virtual Tour". Utah State Capitol. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ^ "J. R. Clancy and Oasis Stage Werks Provide Rigging Solution for Utah State Capitol Chandelier". Light and Sound America. July 9, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Utah House of Representatives. "About". Utah House of Representatives. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Whitney, Susan (August 1, 2004). "Fixer-Upper: State Capitol Building Is Closing for 4-Year, $200 Million Renovation". Deseret News. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Utah State Capitol. |

- Utah State Capitol (official website)

| Preceded by Walker Center |

Tallest Building in Salt Lake City 1916–1973 85 m |

Succeeded by LDS Church Office Building |

- Buildings and structures in Salt Lake City

- Government buildings completed in 1912

- Government buildings in Utah

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Utah

- Government of Utah

- State capitols in the United States

- Domes

- Tourist attractions in Salt Lake City

- 1912 establishments in Utah

- National Register of Historic Places in Salt Lake City