Area 51

| Homey Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A satellite image, taken in 2000, shows dry Groom Lake just north-northeast of the site.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Military Installation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | U.S. Federal Government | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | United States Air Force | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Lincoln County, Nevada, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 4,462 ft / 1,360 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°14′06″N 115°48′40″W / 37.23500°N 115.81111°WCoordinates: 37°14′06″N 115°48′40″W / 37.23500°N 115.81111°W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||||||||

| Location of Homey Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

The United States Air Force facility commonly known as Area 51 is a highly classified remote detachment of Edwards Air Force Base, within the Nevada Test and Training Range. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the correct names for the facility are Homey Airport (ICAO: KXTA) and Groom Lake,[2][3] though the name Area 51 was used in a CIA document from the Vietnam War.[4] The facility has also been referred to as Dreamland and Paradise Ranch,[5][6] among other nicknames. The special use airspace around the field is referred to as Restricted Area 4808 North (R-4808N).[7]

The base's current primary purpose is publicly unknown; however, based on historical evidence, it most likely supports the development and testing of experimental aircraft and weapons systems (black projects).[8] The intense secrecy surrounding the base has made it the frequent subject of conspiracy theories and a central component to unidentified flying object (UFO) folklore.[9][10] Although the base has never been declared a secret base, all research and occurrences in Area 51 are Top Secret/Sensitive Compartmented Information (TS/SCI).[9] On 25 June 2013, following a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed in 2005, the CIA publicly acknowledged the existence of the base for the first time, declassifying documents detailing the history and purpose of Area 51.[11]

Area 51 is located in the southern portion of Nevada in the western United States, 83 miles (134 km) north-northwest of Las Vegas. Situated at its center, on the southern shore of Groom Lake, is a large military airfield. The site was acquired by the United States Air Force in 1955, primarily for the flight testing of the Lockheed U-2 aircraft.[12] The area around Area 51, including the small town of Rachel on the "Extraterrestrial Highway", is a popular tourist destination.

Contents

Geography

Area 51

The original rectangular base of 6 by 10 miles (9.7 by 16.1 km) is now part of the so-called "Groom box", a rectangular area measuring 23 by 25 miles (37 by 40 km), of restricted airspace. The area is connected to the internal Nevada Test Site (NTS) road network, with paved roads leading south to Mercury and west to Yucca Flat. Leading northeast from the lake, the wide and well-maintained Groom Lake Road runs through a pass in the Jumbled Hills. The road formerly led to mines in the Groom basin, but has been improved since their closure. Its winding course runs past a security checkpoint, but the restricted area around the base extends further east. After leaving the restricted area, Groom Lake Road descends eastward to the floor of the Tikaboo Valley, passing the dirt-road entrances to several small ranches, before converging with State Route 375, the "Extraterrestrial Highway",[13] south of Rachel.

Area 51 shares a border with the Yucca Flat region of the Nevada Test Site, the location of 739 of the 928 nuclear tests conducted by the United States Department of Energy at NTS.[14][15][16] The Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository is 44 miles (71 km) southwest of Groom Lake.

Groom Lake

Groom Lake is a salt flat in Nevada used for runways of the Nellis Bombing Range Test Site airport (KXTA) on the north of the Area 51 USAF military installation. The lake at 4,409 ft (1,344 m)[17] elevation is approximately 3.7 miles (6.0 km) from north to south and 3 miles (4.8 km) from east to west at its widest point. Located within the namesake Groom Lake Valley portion of the Tonopah Basin, the lake is 25 mi (40 km) south of Rachel, Nevada.

History

The origin of the Area 51 name is unclear. The most accepted comes from a grid numbering system of the area by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC); while Area 51 is not part of this system, it is adjacent to Area 15. Another explanation is that 51 was used because it was unlikely that the AEC would use the number.[18]

Groom Lake

Lead and silver were discovered in the southern part of the Groom Range in 1864,[19] and the English Groome Lead Mines Limited company financed the Conception Mines in the 1870s, giving the district its name (nearby mines included Maria, Willow and White Lake).[20] The interests in Groom were acquired by J. B. Osborne and partners and patented in 1876, and his son acquired the interests in the 1890s.[20] Claims were incorporated as two 1916 companies with mining continuing until 1918 and resuming after World War II until the early 1950s.[20]

World War II

The airfield on the Groom Lake site began service in 1942 as Indian Springs Air Force Auxiliary Field,[21] and consisted of two unpaved 5000-foot runways aligned NE/SW, NW/SE 37°16′35″N 115°45′20″W / 37.27639°N 115.75556°W.[22]

U-2 program

The Groom Lake test facility was established in April 1955 by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for Project Aquatone, the development of the Lockheed U-2 strategic reconnaissance aircraft.

As part of the project, the director, Richard M. Bissell, Jr., understood that, given the extreme secrecy enveloping the project, the flight test and pilot training programs could not be conducted at Edwards Air Force Base or Lockheed's Palmdale facility. A search for a suitable testing site for the U-2 was conducted under the same extreme security as the rest of the project.[23]

He notified Lockheed, who sent an inspection team out to Groom Lake. According to Lockheed's U-2 designer Kelly Johnson:[23]

We flew over it and within thirty seconds, you knew that was the place ... it was right by a dry lake. Man alive, we looked at that lake, and we all looked at each other. It was another Edwards, so we wheeled around, landed on that lake, taxied up to one end of it. It was a perfect natural landing field ... as smooth as a billiard table without anything being done to it". Johnson used a compass to lay out the direction of the first runway. The place was called "Groom Lake".

The lakebed made an ideal strip from which they could test aircraft, and the Emigrant Valley's mountain ranges and the NTS perimeter, about 100 mi (160 km) north of Las Vegas, protected the test site from visitors.[24] The CIA asked the AEC to acquire the land, designated "Area 51" on the map, and add it to the Nevada Test Site.[11]:56–57

Johnson named the area "Paradise Ranch" to encourage workers to move to a place that the CIA's official history of the U-2 project would later describe as "the new facility in the middle of nowhere"; the name became shortened to "the Ranch".[11]:57[25] On 4 May 1955, a survey team arrived at Groom Lake and laid out a 5,000-foot (1,500 m), north-south runway on the southwest corner of the lakebed and designated a site for a base support facility. "The Ranch", also known as Site II, initially consisted of little more than a few shelters, workshops and trailer homes in which to house its small team.[24] In a little over three months, the base consisted of a single, paved runway, three hangars, a control tower, and rudimentary accommodations for test personnel. The base's few amenities included a movie theatre and volleyball court. Additionally, there was a mess hall, several water wells, and fuel storage tanks. By July 1955, CIA, Air Force, and Lockheed personnel began arriving. The Ranch received its first U-2 delivery on 24 July 1955 from Burbank on a C-124 Globemaster II cargo plane, accompanied by Lockheed technicians on a Douglas DC-3.[24] Regular Military Air Transport Service flights were set up between Area 51 and Lockheed's Burbank, California offices. To preserve secrecy, personnel flew to Nevada on Monday mornings and returned to California on Friday evenings.[11]:72

OXCART program

Project OXCART established in August 1959 for "antiradar studies, aerodynamic structural tests, and engineering designs [and] all later work on the" Lockheed A-12[27] included testing at Groom Lake, which before improvements for OXCART had inadequate facilities: buildings for only 150 people, a 5,000 ft (1,500 m) asphalt runway, and limited fuel, hangar, and shop space.[23] Selected for its seclusion and climate, Groom Lake had received a new official name "Area 51"[23][verification needed] when A-12 test facility construction began in September 1960, including a new 8,500 ft (2,600 m) runway to replace the existing runway (completed by 15 November 1960 with "expansion joints parallel to the direction of aircraft roll" to limit vibration.)[28]

Four years of "Project 51" construction began on 1 October 1960 by Reynolds Electrical and Engineering Company (REECo) with double-shift construction schedules. The contractor upgraded base facilities and built a new 10,000 ft (3,000 m) runway (14/32) diagonally across the southwest corner of the lakebed. An Archimedes curve approximately two miles across was marked on the dry lake so that an A-12 pilot approaching the end of the overrun could abort to the playa instead of plunging the aircraft into the sagebrush. Area 51 pilots called it "The Hook". For crosswind landings two unpaved airstrips (runways 9/27 and 03/21) were marked on the dry lakebed.[29]

By August 1961, construction of the essential facilities was completed (3 surplus Navy hangars were erected on the base's north side—hangars 4, 5, and 6.) A fourth, Hangar 7, was new construction. The original U-2 hangars were converted to maintenance and machine shops. Facilities in the main cantonment area included workshops and buildings for storage and administration, a commissary, control tower, fire station, and housing. The Navy also contributed more than 130 surplus Babbitt duplex housing units for long-term occupancy facilities. Older buildings were repaired, and additional facilities were constructed as necessary. A reservoir pond, surrounded by trees, served as a recreational area one mile north of the base. Other recreational facilities included a gymnasium, movie theatre, and a baseball diamond.[29] A permanent aircraft fuel tank farm was constructed by early 1962 for the special JP-7 fuel required by the A-12. Seven tanks were constructed, with a total capacity of 1,320,000 gallons.

For the arrival of OXCART; security was enhanced and the small civilian mine[specify] in the Groom basin was closed. In January 1962, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) expanded the restricted airspace in the vicinity of Groom Lake. The lakebed became the center of a 600-square-mile addition to restricted area R-4808N.[29]

The CIA facility received eight USAF F-101 Voodoos for training, two T-33 Shooting Star trainers for proficiency flying, a C-130 Hercules for cargo transport, a U-3A for administrative purposes, a helicopter for search and rescue, and a Cessna 180 for liaison use; and Lockheed provided an F-104 Starfighter for use as a chase plane.[29]

The first A-12 test aircraft was covertly trucked from Burbank on 26 February 1962, arrived at Groom Lake on 28 February,[26] was assembled, and made its first flight 26 April 1962 when the base had over 1,000 personnel. Initially, all not connected with a test were herded into the mess hall before each takeoff. This was soon dropped as it disrupted activities and was impractical with the large number of flights.[23] The closed airspace above Groom Lake was within the Nellis Air Force Range airspace, and pilots saw the A-12 20–30 times (at least one signed a secrecy agreement.).[23]

Groom was also the site of the first Lockheed D-21 drone test flight on 22 December 1964 (not launched until 5 March 1966).[26] By the end of 1963, nine A-12s were at Area 51, assigned to the CIA operated "1129th Special Activities Squadron".[30]

Although it was decided[by whom?] on 10 January 1967 to phase out the CIA A-12 program, A-12s at Groom Lake occasionally deployed to Kadena AB, Okinawa, for Project Black Shield in 1967[26] (the 9 A-12s were stored at Palmdale in June 1968 and the 1129th SAS was inactivated.)[30]

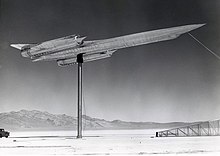

D-21 Tagboard

Following the loss of Gary Powers' U-2 over the Soviet Union, there were several discussions about using the A-12 OXCART as an unpiloted drone aircraft. Although Kelly Johnson had come to support the idea of drone reconnaissance, he opposed the development of an A-12 drone, contending that the aircraft was too large and complex for such a conversion. However, the Air Force agreed to fund the study of a high-speed, high-altitude drone aircraft in October 1962. The Air Force interest seems to have moved the CIA to take action, the project designated "Q-12". By October 1963, the drone's design had been finalized. At the same time, the Q-12 underwent a name change. To separate it from the other A-12-based projects, it was renamed the "D-21". (The "12" was reversed to "21"). "Tagboard" was the project's code name.[23]

The first D-21 was completed in the spring of 1964 by Lockheed. After four more months of checkouts and static tests, the aircraft was shipped to Groom Lake and reassembled. It was to be carried by a two-seat derivative of the A-12, designated the "M-21". When the D-21/M-21 reached the launch point, the first step would be to blow off the D-21's inlet and exhaust covers. With the D-21/M-21 at the correct speed and altitude, the LCO would start the ramjet and the other systems of the D-21. With the D-21's systems activated and running, and the launch aircraft at the correct point, the M-21 would begin a slight pushover, the LCO would push a final button, and the D-21 would come off the pylon".[23]

Difficulties were addressed throughout 1964 and 1965 at Groom Lake with various technical issues. Captive flights showed unforeseen aerodynamic difficulties. By late January 1966, more than a year after the first captive flight, everything seemed ready. The first D-21 launch was made on 5 March 1966 with a successful flight, with the D-21 flying 120 miles with limited fuel. A second D-12 flight was successful in April 1966 with the drone flying 1,200 miles, reaching Mach 3.3 and 90,000 feet. An accident on 30 July 1966 with a fully fueled D-21, on a planned checkout flight suffered from a non-start of the drone after its separation, causing it to collide with the M-21 launch aircraft. The two crewmen ejected and landed in the ocean 150 miles offshore. One crew member was picked up by a helicopter, but the other, having survived the aircraft breakup and ejection, drowned when sea water entered his pressure suit. Kelly Johnson personally cancelled the entire program, having had serious doubts from the start of the feasibility. A number of D-21s had already been produced, and rather than scrapping the whole effort, Johnson again proposed to the Air Force that they be launched from a B-52H bomber.[23]

By late summer of 1967, the modification work to both the D-21 (now designated D-21B) and the B-52Hs were complete. The test program could now resume. The test missions were flown out of Groom Lake, with the actual launches over the Pacific. The first D-21B to be flown was Article 501, the prototype. The first attempt was made on 28 September 1967, and ended in complete failure. As the B-52 was flying toward the launch point, the D-21B fell off the pylon. The B-52H gave a sharp lurch as the drone fell free. The booster fired and was "quite a sight from the ground". The failure was traced to a stripped nut on the forward right attachment point on the pylon. Several more tests were made, none of which met with success. However, the fact is that the resumptions of D-21 tests took place against a changing reconnaissance background. The A-12 had finally been allowed to deploy, and the SR-71 was soon to replace it. At the same time, new developments in reconnaissance satellite technology were nearing operation. Up to this point, the limited number of satellites available restricted coverage to the Soviet Union. A new generation of reconnaissance satellites could soon cover targets anywhere in the world. The satellites' resolution would be comparable to that of aircraft, but without the slightest political risk. Time was running out for the Tagboard.[23]

Several more test flights, including two over China, were made from Beale AFB, California, in 1969 and 1970, to varying degrees of success. On 15 July 1971, Kelly Johnson received a wire canceling the D-21B program. The remaining drones were transferred by a C-5A and placed in dead storage. The tooling used to build the D-21Bs was ordered destroyed. Like the A-12 Oxcart, the D-21B Tagboard drones remained a Black airplane, even in retirement. Their existence was not suspected until August 1976, when the first group was placed in storage at the Davis-Monthan AFB Military Storage and Disposition Center. A second group arrived in 1977. They were labeled "GTD-21Bs" (GT stood for ground training).[23]

Davis-Monthan is an open base, with public tours of the storage area at the time, so the odd-looking drones were soon spotted and photos began appearing in magazines. Speculation about the D-21Bs circulated within aviation circles for years, and it was not until 1982 that details of the Tagboard program were released. However, it was not until 1993 that the B-52/D-21B program was made public. That same year, the surviving D-21Bs were released to museums.[23]

Foreign technology evaluation

During the Cold War, one of the missions carried out by the United States was the test and evaluation of captured Soviet fighter aircraft. Beginning in the late 1960s, and for several decades, Area 51 played host to an assortment of Soviet-built aircraft. Under the HAVE DOUGHNUT, HAVE DRILL and HAVE FERRY programs, the first MiGs flown in the United States were used to evaluate the aircraft in performance, technical, and operational capabilities, pitting the types against U.S. fighters.[31]

This was not a new mission, as testing of foreign technology by the USAF began during World War II. After the war, testing of acquired foreign technology was performed by the Air Technical Intelligence Center (ATIC, which became very influential during the Korean War), under the direct command of the Air Materiel Control Department. In 1961 ATIC became the Foreign Technology Division (FTD), and was reassigned to Air Force Systems Command. ATIC personnel were sent anywhere where foreign aircraft could be found.

The focus of Air Force Systems Command limited the use of the fighter as a tool with which to train the front line tactical fighter pilots.[31] Air Force Systems Command recruited its pilots from the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California, who were usually graduates from various test pilot schools. Tactical Air Command selected its pilots primarily from the ranks of the Weapons School graduates.[31]

In August 1966, Iraqi Air Force fighter pilot Captain Munir Redfa defected, flying his MiG-21 to Israel after being ordered to attack Iraqi Kurd villages with napalm. His aircraft was transferred to Groom Lake within a month to study. In 1968 the US Air Force and Navy jointly formed a project known as Have Doughnut in which Air Force Systems Command, Tactical Air Command, and the U.S. Navy's Air Test and Evaluation Squadron Four (VX-4) flew this acquired Soviet made aircraft in simulated air combat training.[31] Because U.S. possession of the Soviet MiG-21 was, itself, secret, it was tested at Groom Lake. A joint Air Force-Navy team was assembled for a series of dogfight tests.[23]

Comparisons between the F-4 and the MiG-21 indicated that, on the surface, they were evenly matched. But air combat was not just about technology. In the final analysis, it was the skill of the man in the cockpit. The Have Doughnut tests showed this most strongly. When the Navy or Air Force pilots flew the MiG-21, the results were a draw; the F-4 would win some fights, the MiG-21 would win others. There were no clear advantages. The problem was not with the planes, but with the pilots flying them. The pilots would not fly either plane to its limits. One of the Navy pilots was Marland W. "Doc" Townsend, then commander of VF-121, the F-4 training squadron at NAS Miramar. He was an engineer and a Korean War veteran and had flown almost every navy aircraft. When he flew against the MiG-21, he would outmaneuver it every time. The Air Force pilots would not go vertical in the MiG-21. The Have Doughnut project officer was Tom Cassidy, a pilot with VX-4, the Navy's Air Development Squadron at Point Mugu. He had been watching as Townsend "waxed" the air force MiG-21 pilots. Cassidy climbed into the MiG-21 and went up against Townsend's F-4. This time the result was far different. Cassidy was willing to fight in the vertical, flying the plane to the point where it was buffeting, just above the stall. Cassidy was able to get on the F-4's tail. After the flight, they realized the MiG-21 turned better than the F-4 at lower speeds. The key was for the F-4 to keep its speed up. What had happened in the sky above Groom Lake was remarkable. An F-4 had defeated the MiG-21; the weakness of the Soviet plane had been found. Further test flights confirmed what was learned. It was also clear that the MiG-21 was a formidable enemy. United States pilots would have to fly much better than they had been to beat it. This would require a special school to teach advanced air combat techniques.[23]

On 12 August 1968, two Syrian air force lieutenants, Walid Adham and Radfan Rifai, took off in a pair of MiG-17Fs on a training mission. They lost their way and, believing they were over Lebanon, landed at the Beset Landing Field in northern Israel. (One version has it that they were led astray by an Arabic-speaking Israeli).[23] Prior to the end of 1968 these MiG-17s were transferred from Israeli stocks and added to the Area 51 test fleet. The aircraft were given USAF designations and fake serial numbers so that they could be identified in DOD standard flight logs. As in the earlier program, a small group of Air Force and Navy pilots conducted mock dogfights with the MiG-17s. Selected instructors from the Navy's Top Gun school at NAS Miramar, California, were chosen to fly against the MiGs for familiarization purposes. Very soon, the MiG-17's shortcomings became clear. It had an extremely simple, even crude, control system which lacked the power-boosted controls of American aircraft. The F-4's twin engines were so powerful it could accelerate out of range of the MiG-17's guns in thirty seconds. It was important for the F-4 to keep its distance from the MiG-17. As long as the F-4 was one and a half miles from the MiG-17, it was outside the reach of the Soviet fighter's guns, but the MiG was within reach of the F-4's missiles.[23]

The data from the Have Doughnut and Have Drill tests were provided to the newly formed Top Gun school at NAS Miramar. By 1970, the Have Drill program was expanded; a few selected fleet F-4 crews were given the chance to fight the MiGs. The most important result of Project Have Drill is that no Navy pilot who flew in the project defeated the MiG-17 Fresco in the first engagement. The Have Drill dogfights were by invitation only. The other pilots based at Nellis Air Force Base were not to know about the U.S.-operated MiGs. To prevent any sightings, the airspace above the Groom Lake range was closed. On aeronautical maps, the exercise area was marked in red ink. The forbidden zone became known as "Red Square".[23]

During the remainder of the Vietnam War, the Navy kill ratio climbed to 8.33 to 1. In contrast, the Air Force rate improved only slightly to 2.83 to 1. The reason for this difference was Top Gun. The Navy had revitalized its air combat training, while the Air Force had stayed stagnant. Most of the Navy MiG kills were by Top Gun graduates.[citation needed]

In May 1973, Project Have Idea was formed which took over from the older Have Doughnut, Have Ferry and Have Drill projects and the project was transferred to the Tonopah Test Range Airport. At Tonopah testing of foreign technology aircraft continued and expanded throughout the 1970s and 1980s.[31]

Area 51 also hosted another foreign materiel evaluation program called HAVE GLIB. This involved testing Soviet tracking and missile control radar systems. A complex of actual and replica Soviet-type threat systems began to grow around "Slater Lake", a mile northwest of the main base, along with an acquired Soviet "Barlock" search radar placed at Tonopah Air Force Station. They were arranged to simulate a Soviet-style air defense complex.

The Air Force began funding improvements to Area 51 in 1977 under project SCORE EVENT. In 1979, the CIA transferred jurisdiction of the Area 51 site to the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards AFB, California. Mr. Sam Mitchell, the last CIA commander of Area 51, relinquished command to USAF Lt. Col. Larry D. McClain.

Have Blue/F-117 program

The Lockheed Have Blue prototype stealth fighter (a smaller proof-of-concept model of the F-117 Nighthawk) first flew at Groom in December 1977.[32]

In 1978, the Air Force awarded a full-scale development contract for the F-117 to Lockheed Corporation's Advanced Development Projects. On 17 January 1981 the Lockheed test team at Area 51 accepted delivery of the first full Scale Development (FSD) prototype 79–780, designated YF-117A. At 6:05 am on 18 June 1981 Lockheed Skunk Works test pilot Hal Farley lifted the nose of YF-117A 79–780' off the runway of Area 51.[33]

Meanwhile, Tactical Air Command (TAC) decided to set up a group-level organization to guide the F-117A to an initial operating capability. That organization became the 4450th Tactical Group (Initially designated "A Unit"), which officially activated on 15 October 1979 at Nellis AFB, Nevada, although the group was physically located at Area 51. The 4450th TG also operated the A-7D Corsair II as a surrogate trainer for the F-117A, and these operations continued until 15 October 1982 under the guise of an avionics test mission.[33]

Flying squadrons of the 4450th TG were the 4450th Tactical Squadron (Initially designated "I Unit") activated on 11 June 1981, and 4451st Tactical Squadron (Initially designated "P Unit") on 15 January 1983. The 4450th TS, stationed at Area 51, was the first F-117A squadron, while the 4451st TS was stationed at Nellis AFB and was equipped with A-7D Corsair IIs painted in a dark motif, tail coded "LV". Lockheed test pilots put the YF-117 through its early paces. A-7Ds was used for pilot training before any F-117A's had been delivered by Lockheed to Area 51, later the A-7D's were used for F-117A chase testing and other weapon tests at the Nellis Range.

15 October 1982 is important to the program because on that date Major Alton C. Whitley, Jr. became the first USAF 4450th TG pilot to fly the F-117A.[33]

Although ideal for testing, Area 51 was not a suitable location for an operational group, so a new covert base had to be established for F-117 operations.[34] Tonopah Test Range Airport was selected for operations of the first USAF F-117 unit, the 4450th Tactical Group (TG).[35] From October 1979, the Tonopah Airport base was reconstructed and expanded. The 6,000 ft runway was lengthened to 10,000 ft. Taxiways, a concrete apron, a large maintenance hangar, and a propane storage tank were added.[36]

By early 1982, four more YF-117A airplanes were operating out of the southern end of the base, known as the "Southend" or "Baja Groom Lake". After finding a large scorpion in their offices, the testing team (Designated "R Unit") adopted it as their mascot and dubbed themselves the "Baja Scorpions". Testing of a series of ultra-secret prototypes continued at Area 51 until mid-1981, when testing transitioned to the initial production of F-117 stealth fighters. The F-117s were moved to and from Area 51 by C-5 under the cloak of darkness, in order to maintain program security. This meant that the aircraft had to be defueled, disassembled, cradled, and then loaded aboard the C-5 at night, flown to Lockheed, and unloaded at night before the real work could begin. Of course, this meant that the reverse actions had to occur at the end of the depot work before the aircraft could be reassembled, flight-tested, and redelivered, again under the cover of darkness. In addition to flight-testing, Groom performed radar profiling, F-117 weapons testing, and was the location for training of the first group of frontline USAF F-117 pilots.

While the "Baja Scorpions" were working on the F-117, there was also another group at work in secrecy, known as "the Whalers" working on Tacit Blue. A fly-by-wire technology demonstration aircraft with curved surfaces and composite material, to evade radar, it was a prototype, and never went into production. Nevertheless, this strange-looking aircraft was responsible for many of the stealth technology advances that were used on several other aircraft designs, and had a direct influence on the B-2; with first flight of Tacit Blue being performed on February 5, 1982, by Northrop Grumman test pilot, Richard G. Thomas.

Production FSD airframes from Lockheed were shipped to Area 51 for acceptance testing. As the Baja Scorpions tested the aircraft with functional check flights and L.O. verification, the operational airplanes were then transferred to the 4450th TG.[37]

On 17 May 1982, the move of the 4450th TG from Groom Lake to Tonopah was initiated, with the final components of the move completed in early 1983. Production FSD airframes from Lockheed were shipped to Area 51 for acceptance testing. As the Baja Scorpions tested the aircraft with functional check flights and L.O. verification, the operational airplanes were then transferred to the 4450th TG at Tonopah. [37]

The R-Unit was inactivated on 30 May 1989. Upon inactivation, the unit was reformed as Detachment 1, 57th Fighter Weapons Wing (FWW). In 1990 the last F-117A (843) was delivered from Lockheed. After completion of acceptance flights at Area 51 of this last new F-117A aircraft, the flight test squadron continued flight test duties of refurbished aircraft after modifications by Lockheed. In February/March 1992 the test unit moved from Area 51 to the USAF Palmdale Plant 42 and was integrated with the Air Force Systems Command 6510th Test Squadron. Some testing, especially RCS verification and other classified activity was still conducted at Area 51 throughout the operational lifetime of the F-117. The recently inactivated (2008) 410th Flight Test Squadron traces its roots, if not its formal lineage to the 4450th TG R-unit. [37]

Later operations

Since the F-117 became operational in 1983, operations at Groom Lake have continued. The base and its associated runway system were expanded, including expansion of housing and support facilities.[3][38] In 1995, the federal government expanded the exclusionary area around the base to include nearby mountains that had hitherto afforded the only decent overlook of the base, prohibiting access to 3,972 acres (16.07 km2) of land formerly administered by the Bureau of Land Management.[3] On October 22, 2015 a federal judge signed an order giving land that belonged to a Nevada family since the 1870s to the United States Air Force for expanding Area 51. According to the judge, the land that overlooked the base was taken to address security and safety concerns connected with their training and testing.[39]

Legal status

U.S. government's positions on Area 51

The amount of information the United States government has been willing to provide regarding Area 51 has generally been minimal. The area surrounding the lake is permanently off-limits to both civilian and normal military air traffic. Security clearances are checked regularly; cameras and weaponry are not allowed.[10] Even military pilots training in the NAFR risk disciplinary action if they stray into the exclusionary "box" surrounding Groom's airspace.[5] Surveillance is supplemented using buried motion sensors.[40] Area 51 is a common destination for Janet, the de facto name of a small fleet of passenger aircraft operated on behalf of the United States Air Force to transport military personnel, primarily from McCarran International Airport.

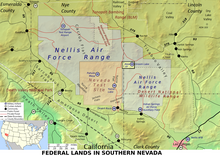

The USGS topographic map for the area only shows the long-disused Groom Mine.[41] A civil aviation chart published by the Nevada Department of Transportation shows a large restricted area, defined as part of the Nellis restricted airspace.[42] The National Atlas page showing federal lands in Nevada shows the area as lying within the Nellis Air Force Base.[43] Higher resolution (and more recent) images from other satellite imagery providers (including Russian providers and the IKONOS) are commercially available.[3] These show the runway markings, base facilities, aircraft, and vehicles.

When documents that mention the Nevada Test Site (NTS) and operations at Groom are declassified, mentions of Area 51 and Groom Lake are routinely redacted.[citation needed] One exception is a 1967 memo from CIA director Richard Helms regarding the deployment of three OXCART aircraft from Groom to Kadena Air Base to perform reconnaissance over North Vietnam. Although most mentions of OXCART's home base are redacted in this document, as is a map showing the aircraft's route from there to Okinawa, the redactor appears to have missed one mention: page 15 (page 17 in the PDF), section No. 2 ends "Three OXCART aircraft and the necessary task force personnel will be deployed from Area 51 to Kadena."[4]

On 25 June 2013, CIA released an official history of the U-2 and OXCART projects that officially acknowledged the existence of Area 51. The release was in response to a Freedom of Information Act request submitted in 2005 by Jeffrey T. Richelson of George Washington University's National Security Archives, and contain numerous references to Area 51 and Groom Lake, along with a map of the area.[11][44][45][46]

Environmental lawsuit

In 1994, five unnamed civilian contractors and the widows of contractors Walter Kasza and Robert Frost sued the USAF and the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Their suit, in which they were represented by George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley, alleged they had been present when large quantities of unknown chemicals had been burned in open pits and trenches at Groom. Biopsies taken from the complainants were analyzed by Rutgers University biochemists, who found high levels of dioxin, dibenzofuran, and trichloroethylene in their body fat. The complainants alleged they had sustained skin, liver, and respiratory injuries due to their work at Groom, and that this had contributed to the deaths of Frost and Kasza. The suit sought compensation for the injuries they had sustained, claiming the USAF had illegally handled toxic materials, and that the EPA had failed in its duty to enforce the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (which governs handling of dangerous materials). They also sought detailed information about the chemicals to which they were allegedly exposed, hoping this would facilitate the medical treatment of survivors. Congressman Lee H. Hamilton, former chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, told 60 Minutes reporter Lesley Stahl, "The Air Force is classifying all information about Area 51 in order to protect themselves from a lawsuit."

Citing the State Secrets Privilege, the government petitioned trial judge U.S. District Judge Philip Pro (of the United States District Court for the District of Nevada in Las Vegas) to disallow disclosure of classified documents or examination of secret witnesses, alleging this would expose classified information and threaten national security.[47] When Judge Pro rejected the government's argument, President Bill Clinton issued a Presidential Determination, exempting what it called, "The Air Force's Operating Location Near Groom Lake, Nevada" from environmental disclosure laws. Consequently, Pro dismissed the suit due to lack of evidence. Turley appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, on the grounds that the government was abusing its power to classify material. Secretary of the Air Force Sheila E. Widnall filed a brief that stated that disclosures of the materials present in the air and water near Groom "can reveal military operational capabilities or the nature and scope of classified operations." The Ninth Circuit rejected Turley's appeal,[48] and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear it, putting an end to the complainants' case.

The President continues to annually issue a determination continuing the Groom exception.[49][50][51] This, and similarly tacit wording used in other government communications, is the only formal recognition the U.S. Government has ever given that Groom Lake is more than simply another part of the Nellis complex.

An unclassified memo on the safe handling of F-117 Nighthawk material was posted on an Air Force web site in 2005. This discussed the same materials for which the complainants had requested information (information the government had claimed was classified). The memo was removed shortly after journalists became aware of it.[52]

Civil aviation identification

In December 2007, airline pilots noticed that the base had appeared in their aircraft navigation systems' latest Jeppesen database revision with the ICAO airport identifier code of KXTA and listed as "Homey Airport".[53] The probably inadvertent release of the airport data led to advice by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) that student pilots should be explicitly warned about KXTA, not to consider it as a waypoint or destination for any flight even though it now appears in public navigation databases.[53]

Security

Signage around the base perimeter advises that deadly force is authorized against trespassers.[54]

1974 Skylab photography

In January 2006, space historian Dwayne A. Day published an article in online aerospace magazine The Space Review titled "Astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident". The article was based on a memo written in 1974 to CIA director William Colby by an unknown CIA official. The memo reported that astronauts on board Skylab 4 had, as part of a larger program, inadvertently photographed a location of which the memo said:

There were specific instructions not to do this. <redacted> was the only location which had such an instruction.

Although the name of the location was obscured, the context led Day to believe that the subject was Groom Lake. As Day noted:

[I]n other words, the CIA considered no other spot on Earth to be as sensitive as Groom Lake.[55][56]

The memo details debate between federal agencies regarding whether the images should be classified, with Department of Defense agencies arguing that it should, and NASA and the State Department arguing against classification. The memo itself questions the legality of unclassified images to be retroactively classified.

Remarks on the memo,[57] handwritten apparently by DCI (Director of Central Intelligence) Colby himself, read:

[Secretary of State Rusk] did raise it—said State Dept. people felt strongly. But he inclined leave decision to me (DCI)—I confessed some question over need to protect since:

- USSR has it from own sats

- What really does it reveal?

- If exposed, don't we just say classified USAF work is done there?

The declassified documents do not disclose the outcome of discussions regarding the Skylab imagery. The behind-the-scenes debate proved moot as the photograph appeared in the Federal Government's Archive of Satellite Imagery along with the remaining Skylab 4 photographs, with no record of anyone noticing until Day identified it in 2007.[58]

Other satellite imagery

Other satellite imagery is also available, including images that show what appears to be F-16 Fighting Falcon aircraft stationed on the base.[59]

UFO and other conspiracy theories

Its secretive nature and undoubted connection to classified aircraft research, together with reports of unusual phenomena, have led Area 51 to become a focus of modern UFO and other conspiracy theories. Some of the activities mentioned in such theories at Area 51 include:[citation needed]

- The storage, examination, and reverse engineering of crashed alien spacecraft (including material supposedly recovered at Roswell), the study of their occupants (living and dead; see grey alien), and the manufacture of aircraft based on alien technology.

- Meetings or joint undertakings with extraterrestrials.

- The development of exotic energy weapons for the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) or other weapons programs.

- The development of means of weather control.

- The development of time travel and teleportation technology.

- The development of unusual and exotic propulsion systems related to the Aurora Program.

- Activities related to a supposed shadowy one world government or the Majestic 12 organization.

Many of the hypotheses concern underground facilities at Groom or at Papoose Lake (also known as "S-4 location"), 8.5 miles (13.7 km) south, and include claims of a transcontinental underground railroad system, a disappearing airstrip (nicknamed the "Cheshire Airstrip", after Lewis Carroll's Cheshire cat) which briefly appears when water is sprayed onto its camouflaged asphalt,[60] and engineering based on alien technology. Publicly available satellite imagery, however, reveals clearly visible landing strips at Groom Dry Lake, but not at Papoose Lake.

In the mid-1950s, civilian aircraft flew under 20,000 feet while military aircraft flew under 40,000 feet. Once the U-2 began flying at above 60,000 feet, an unexpected side effect was an increasing number of UFO sighting reports. Sightings occurred most often during early evenings hours, when airline pilots flying west saw the U-2's silver wings reflect the setting sun, giving the aircraft a "fiery" appearance. Many sighting reports came to the Air Force's Project Blue Book, which investigated UFO sightings, through air-traffic controllers and letters to the government. The project checked U-2 and later OXCART flight records to eliminate the majority of UFO reports it received during the late 1950s and 1960s, although it could not reveal to the letter writers the truth behind what they saw.[11]:72–73 Similarly, veterans of experimental projects such as OXCART and NERVA at Area 51 agree that their work (including 2,850 OXCART test flights alone) inadvertently prompted many of the UFO sightings and other rumors:[9]

The shape of OXCART was unprecedented, with its wide, disk-like fuselage designed to carry vast quantities of fuel. Commercial pilots cruising over Nevada at dusk would look up and see the bottom of OXCART whiz by at 2,000-plus mph. The aircraft's titanium body, moving as fast as a bullet, would reflect the sun's rays in a way that could make anyone think, UFO.[61]

They believe that the rumors helped maintain secrecy over Area 51's actual operations.[10] While the veterans deny the existence of a vast underground railroad system, many of Area 51's operations did (and presumably still do) occur underground.[9]

Several people have claimed knowledge of events supporting Area 51 conspiracy theories. These have included Bob Lazar, who claimed in 1989 that he had worked at Area 51's "Sector Four (S-4)", said to be located underground inside the Papoose Range near Papoose Lake. Lazar has stated he was contracted to work with alien spacecraft that the U.S. government had in its possession.[62]

Similarly, the 1996 documentary Dreamland directed by Bruce Burgess included an interview with a 71-year-old mechanical engineer who claimed to be a former employee at Area 51 during the 1950s. His claims included that he had worked on a "flying disc simulator" which had been based on a disc originating from a crashed extraterrestrial craft and was used to train US Pilots. He also claimed to have worked with an extraterrestrial being named "J-Rod" and described as a "telepathic translator".[63]

In 2004, Dan Burisch (pseudonym of Dan Crain) claimed to have worked on cloning alien viruses at Area 51, also alongside the alien named "J-Rod". Burisch's scholarly credentials are the subject of much debate, as he was apparently working as a Las Vegas parole officer in 1989 while also earning a PhD at State University of New York (SUNY).[64]

In popular culture

Novels, films, television programs, and other fictional portrayals of Area 51 describe it—or a fictional counterpart—as a haven for extraterrestrials, time travel, and sinister conspiracies, often linking it with the Roswell UFO incident.

- In the 1996 action film Independence Day, the United States military uses alien technology captured at Roswell to attack the invading alien fleet from Area 51. The president of the United States dismissed the site's existence as a myth until his secretary revealed it to him, at which he questioned where the off-the-book-funding comes from. In the 2016 sequel, Independence Day: Resurgence, that 20 years after the events of the first film, Area 51 has become the Space Defense Headquarters for Earth Space Defense (ESD).

- The 2015 film Area 51 (film) is a mockumentary which depicts four individuals attempting to sneak into Area 51.

- The "Hangar 51"[65] government warehouse of the Indiana Jones films stores, among other exotic items, the Ark of the Covenant and an alien corpse from Roswell.

- In the television series Stargate SG-1, Area 51 serves as a storage and testing facility for advanced weapon systems and aircraft/spacecraft designed using alien technology discovered after the Stargate was activated. The series states that prior to the Stargate's activation, rumors of alien technology or individuals existing at Area 51 were unfounded.

- The television series Seven Days takes place inside Area 51, with the base containing a covert NSA time travel operation using alien technology recovered from Roswell.

- The 2005 video game Area 51 is set in the base, and mentions the Roswell and moon landing hoax conspiracy theories.

- Bob Mayer's Area 51 novel series (originally written under his pen name, Robert Doherty) is set on the base, and Operation Highjump is said to have been a cover for an expedition to excavate flying saucers buried under Antarctica's ice shelf by long-ago extraterrestrial visitors.[66]

- The 2000 video games Deus Ex and Perfect Dark feature Area 51, and the 1995 arcade game Area 51 puts the player in control of a soldier attempting to stop the takeover of the base by aliens.

- Episode 7 of season 6 of the TV series Archer, titled "Nellis", is set in Area 51, where Pam and Krieger encounter extraterrestrials. However, Area 51 is fictionalized as part of nearby Nellis Air Force Base, rather than being part of Edwards Air Force Base.

- At least two Warhammer 40K stories involve unrelated places named Regio Quinquaginta-Unus. In The Greater good (a Ciaphas Cain novel by Sandy Mitchell) it's a secret Adeptus Mechanicus site holding alien artifacts, and, it turns out, live Genestealer specimens as well.

See also

- Black project

- Black site

- Dugway Proving Ground, a restricted facility in the Utah desert.

- Groom Range, a mountain range north of the lakebed.

- Kapustin Yar, a Russian rocket launch and development site.

- Special Access Program

- Title 51 of the United States Code, National and Commercial Space Programs

- Tonopah Test Range Airport, a large airfield also within the Nellis Range.

- Tonopah Test Range, also known as Area 52

- Woomera Test Range, a defense and aerospace testing area in Australia.

References

Specific

- ^ "Don't ask, don't tell: Area 51 gets airport identifier". www.aopa.org. 1 October 2008.

- ^ "Intelligence Officers Bookshelf — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Overhead: Groom Lake — Area 51". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b Richard Helms (15 May 1967). ""OXCART reconnaissance of North Vietnam", Memo to the Deputy Secretary of Defense from the office of CIA Director Richard Helms, 15 May 1967". CIA. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. (the full declassified document is mirrored at Wikimedia Commons)

- ^ a b Hall, George; Skinner, Michael (1993). Red Flag. Motorbooks International. ISBN 978-0-87938-759-4.

- ^ Rich, Ben R; Janos, Leo (1994). Skunk Works: A personal memoir of my years at Lockheed. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-316-74300-6.

Kelly [Johnson, the U2's designer] had jokingly nicknamed this godforsaken place Paradise Ranch, hoping to lure young and innocent flight crews.

- ^ "Flight Planning / Aeronautical Charts". SkyVector. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ Rich, Ben R; Janos, Leo (1994). Skunk Works: A personal memoir of my years at Lockheed. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-316-74300-6.

... a sprawling facility, bigger than some municipal airports, a test range for sensitive aviation projects.

- ^ a b c d Jacobsen, Annie (2012). Area 51: An Uncensored History of America's Top Secret Military Base. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0-316-20230-4.

- ^ a b c Lacitis, Erik (27 March 2010). "Area 51 vets break silence: Sorry, but no space aliens or UFOs". Seattle Times Newspaper. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Pedlow, Gregory W.; Welzenbach, Donald E. (1992). The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and OXCART Programs, 1954–1974. Washington DC: History Staff, Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Area 51 'declassified' in U-2 spy plane history". BBC News. BBC. 16 August 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Regenold, Stephen (13 April 2007). "Lonesome Highway to Another World?". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ "US Department of Energy. Nevada Operations Office. United States Nuclear Tests: July 1945 through September 1992 (December 2000)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ http://ndep.nv.gov/boff/nts-use.jpg

- ^ https://fas.org/nuke/guide/usa/facility/nts_fig1.gif

- ^ "Query Form For The United States And Its Territories". U.S. Board on Geographic Names. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- "Groom Lake (GNIS code 840824)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Strickland, Jonathan. "How Area 51 Works". How Stuff Work.

- ^ [1] Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c "Groom Mining District Collection 99-19". Knowledgecenter.unr.edu. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Mueller, Robert. Active Air Force Bases Within the United States of America on 17 September 1982 (PDF). Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Center for Air Force History, USAF. ISBN 0-912799-53-6.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Peebles, Curtis (1999). Dark Eagles, Revised Edition. Novato, CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-696-X.

- ^ a b c Peebles, Curtis (2000). Shadow Flights: America's Secret Air War Against the Soviet Union. Novato, CA: Presidio Press. pp. 141–144. ISBN 978-0-89141-700-2.

I gave it a ten plus [score] ... a dry lake bed around three and a half miles around", and describes Tony LeVier showing the lake to Johnson and Bissell, and Johnson deciding to locate the runway "at south end of lake

- ^ Powers, Francis (1960). Operation Overflight: A Memoir of the U-2 Incident. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 15,19–20,22–23. ISBN 9781574884227.

- ^ a b c d A-12, YF-12A, & SR-71 Timeline of Events (Report).

30 Oct 1967 Dennis Sullivan flying an A-12 mission over North Vietnam had 6 missiles launched against him, 3 detonated, on post flight inspection, they found a small piece of metal from missile imbeded in lower wing fillet area (LSW)

- ^ The U-2's Intended Successor: Project Oxcart, 1956–1968 (Report). October 1994.

The new 8,500-foot runway was completed by 15 November 1960.

- ^ "OSA History, chap. 20, pp. 39–40, 43, 51 ... "OXCART Story" pp. 7–9 (S) (cited by The U-2's Intended Successor")

- ^ a b c d "The Oxcart Story". Cia.gov. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b "U-2 and SR-71 Units, Bases and Detachments". Ais.org. 1995. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Steve Davies: "Red Eagles. America's Secret MiGs", Osprey Publishing, 2008

- ^ Rich, pp. 56–60

- ^ a b c http://www.usafpatches.com/pubs/stealth.pdf

- ^ "Area 51 Test Site". F-117A. 14 July 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "4450th TG". F-117A. 1 April 2002. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Tonopah Test Range (TTR)". F-117A. 14 July 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "JTF "Baja Scorpions" of Groom Lake". F-117A. 14 July 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Mary Motta (22 April 2000). "Images of Top-Secret U.S. Air Base Show Growth". space.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2001.

- ^ Stephen Gutowski (October 22, 2015). "Feds Expand Area 51 by Taking Family’s Property". freebeacon.com. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- ^ Kevin Poulsen (25 May 2004). "Area 51 hackers dig up trouble". Securityfocus.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Groom Mine, NV — N37.34583° W115.76583°". Topoquest.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ http://www.nevadadot.com/uploadedFiles/NDOT/Traveler_Info/Maps/Nevada%20Aviaton%202013-2014%20Front.pdf

- ^ nationalatlas.gov. "Map of Federal lands in Nevada" (PDF). US Department of the Interior. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "CIA acknowledges its mysterious Area 51 test site for first time". Reuters Archive. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Area 51 officially acknowledged, mapped in newly released documents". CNN. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Leiby, Richard (17 August 2013). "Government officially acknowledges existence of Area 51, but not the UFOs". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Rogers, Keith (June 4, 2002). "Federal judges to hear case involving Area 51". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ^ http://archive.ca9.uscourts.gov/coa/newopinions.nsf/77F9FB6C3552927E88256D05007AE266/%24file/0016378.pdf?openelement

- ^ "2000 Presidential Determination". Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ "2002 Presidential Determination". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. 18 September 2002. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ "2003 Presidential Determination". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. 16 September 2003. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ "Warnings for emergency responders kept from Area 51 workers". Las Vegas Review-Journal. 21 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b Marsh, Alton K. (10 January 2008). "Don't ask, don't tell: Area 51 gets airport identifier — Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association". Aopa.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Hearst Magazines (April 2000). Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. pp. 142–.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. (9 January 2006). "Astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident". The Space Review (online). Archived from the original on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ "Presidential Determination No. 2003–39". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. 16 September 2003. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ "CIA memo to DCI Colby" (PDF). Hosted by The Space Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. (26 November 2007). "Secret Apollo". The Space Review (online). Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ "Wikimapia — Let's describe the whole world!". wikimapia.org. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ Mahood, Tom (October 1996). "The Cheshire Airstrip". Archived from the original on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ Jacobsen, Annie (5 April 2009). "The Road to Area 51". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "S4 Sport Model – Cetin BAL – GSM:+90 05366063183 – Turkey / Denizli". Zamandayolculuk.com. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ Dreamland, Transmedia and Dandelion Production for Sky Television (1996).

- ^ Sheaffer, Robert (November–December 2004). "Tunguska 1, Roswell 0". Skeptical Inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. 28 (6). Archived from the original on 13 March 2009.

- ^ Rinzler, J.W.; Bouzereau, Laurent (2008). The Complete Making of Indiana Jones. London: Ebury. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-09-192661-8.

- ^ Doherty, Robert (10 February 1997). Area 51 (Area 51 #1). Mass Market Paperback. ISBN 9780440220732.

General

- Rich, Ben R.; Janos, Leo (1994). Skunk Works: A personal memoir of my years at Lockheed. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-74300-6

- Darlington, David (1998). Area 51: The Dreamland Chronicles. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6040-9

- Patton, Phil (1998). Dreamland: Travels Inside the Secret World of Roswell and Area 51. New York: Villard / Random House ISBN 978-0-375-75385-5

- Area 51 resources at the Federation of American Scientists.

- Lesley Stahl "Area 51 / Catch 22" 60 Minutes CBS Television 17 March 1996, a US TV news magazine's segment about the environmental lawsuit.

- Inside Area 51, an index of articles from the Las Vegas Review-Journal. Inside Area 51 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2010-02-18).

- Jacobsen, Annie (2011). "Area 51". New York, Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-13294-7 (hc)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Area 51. |

General

- Dreamland Resort – Detailed history of Area 51

- Roadrunners Internationale – Covering the history of the U2 and A-12 Blackbird spy plane projects

- "How Area 51 Works", on HowStuffWorks

Maps and photographs

- The site Wikimapia

- Dreamland Resort's map of Area 51 buildings

- Dreamland Resort Maps – Maps of Area 51 and Google Earth plug-ins

- Topographic Map of the Emigrant Valley / Groom area

- Photographs of McCarran EG&G terminal and JANET aircraft

- Official FAA aeronautical chart of Groom Lake

- Historical pictures of Groom Lake, Groom Lake Mining District, Department of Special Collections, Digital Image Collections, University of Nevada, Reno, accessed 30 January 2009

- Conspiracy theories in the United States

- Research installations of the United States Air Force

- Buildings and structures in Lincoln County, Nevada

- Military facilities in Nevada

- American secret military programs

- Secret places in the United States

- Installations of the Central Intelligence Agency

- 1942 establishments in Nevada

- UFO culture in the United States