NATO

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| North Atlantic Treaty Organization Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique Nord |

|

| Formation | 4 April 1949 |

|---|---|

| Type | Military alliance |

| Headquarters | Brussels, Belgium |

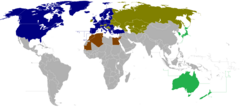

| Membership | 26 member states |

| Official languages | English, French[1] |

| Secretary General | Jaap de Hoop Scheffer |

| Website | |

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); French: Organisation du Traité de l'Atlantique Nord (OTAN); (also called the North Atlantic Alliance, the Atlantic Alliance, or the Western Alliance) is a military alliance, established by the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949. With headquarters in Brussels, Belgium,[2] the organization established a system of collective defence whereby its member states agree to mutual defence in response to an attack by any external party.

[edit] Beginnings

The Treaty of Brussels, signed on 17 March 1948 by Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and the United Kingdom, is considered the precursor to the NATO agreement. This treaty established a military alliance, later to become the Western European Union. However, American participation was thought necessary in order to counter the military power of the Soviet Union, and therefore talks for a new military alliance began almost immediately.

These talks resulted in the North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed in Washington, D.C. on 4 April 1949. It included the five Treaty of Brussels states, as well as the United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Iceland. Three years later, on 18 February 1952, Greece and Turkey also joined.

| “ | The Parties of NATO agreed that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all. Consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence will assist the Party or Parties being attacked, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. | ” |

"Such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force" does not necessarily mean that other member states will respond with military action against the aggressor(s). Rather they are obliged to respond, but maintain the freedom to choose how they will respond. This differs from Article IV of the Treaty of Brussels (which founded the Western European Union) which clearly states that the response must include military action. It is however often assumed that NATO members will aid the attacked member militarily. Further, the article limits the organisation's scope to Europe and North America, which explains why the invasion of the British Falkland Islands did not result in NATO involvement.

In 1954, the Soviet Union suggested that it should join NATO to preserve peace in Europe[3]. The NATO countries ultimately rejected this proposal.

The incorporation of West Germany into the organisation on 9 May 1955 was described as "a decisive turning point in the history of our continent" by Halvard Lange, Foreign Minister of Norway at the time.[4] Indeed, one of its immediate results was the creation of the Warsaw Pact, signed on 14 May 1955 by the Soviet Union and its satellite states, as a formal response to this event, thereby delineating the two opposing sides of the Cold War.

[edit] Early Cold War

- Further information: Cold War

The unity of NATO was breached early on in its history, with a crisis occurring during Charles de Gaulle's presidency of France from 1958 onward. De Gaulle protested the United States' hegemonic role in the organisation and what he perceived as a special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom. In a memorandum sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan on 17 September 1958, he argued for the creation of a tripartite directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the United States and the United Kingdom, and also for the expansion of NATO's coverage to include geographical areas of interest to France, most notably Algeria, where France was waging a counter-insurgency and sought NATO assistance.

Considering the response given to be unsatisfactory, de Gaulle began to build an independent defence for his country. On 11 March 1959, France withdrew its Mediterranean fleet from NATO command; three months later, in June 1959, de Gaulle banned the stationing of foreign nuclear weapons on French soil. This caused the United States to transfer two hundred military aircraft out of France and return control of the ten major air force bases it had operated in France since 1950 to the French by 1967. The last of these was the Toul-Rosières Air Base, home of the 26th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, which was relocated to Ramstein Air Base in West Germany.

In the meantime, France had initiated an independent nuclear deterrence programme, spearheaded by the "Force de frappe" ("Striking force"). France tested its first nuclear weapon, Gerboise Bleue, on 13 February 1960.

Though France showed solidarity with the rest of NATO during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, de Gaulle continued his pursuit of an independent defence by removing France's Atlantic and Channel fleets from NATO command. In 1966, all French armed forces were removed from NATO's integrated military command, and all non-French NATO troops were asked to leave France. This withdrawal precipitated the relocation of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) from Paris to Casteau, north of Mons, Belgium, by 16 October 1967. France remained a member of the alliance throughout this period and subsequently rejoined NATO's Military Committee in 1995, and intensified working relations with the military structure. However, France has not yet rejoined the integrated military command and no non-French NATO troops are allowed to be based on its land.

The creation of NATO necessitated the standardisation of military technology and unified strategy, through Command, Control and Communications centres (aka C4ISTAR). The STANAG (Standardisation Agreement) insured such coherence. Hence, the 7.62×51 NATO rifle cartridge was introduced in the 1950s as a standard firearm cartridge among many NATO countries. Fabrique Nationale's FAL became the most popular 7.62 NATO rifle in Europe and served into the early 1990s. Also, aircraft marshalling signals were standardised, so that any NATO aircraft could land at any NATO base.

[edit] Détente

During most of the duration of the Cold War, NATO maintained a holding pattern with no actual military engagement as an organisation. On 1 July 1968, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty opened for signature: NATO argued that its nuclear weapons sharing arrangements did not breach the treaty as U.S. forces controlled the weapons until a decision was made to go to war, at which point the treaty would no longer be controlling. Few states knew of the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements at that time, and they were not challenged.

On 30 May 1978, NATO countries officially defined two complementary aims of the Alliance, to maintain security and pursue détente. This was supposed to mean matching defences at the level rendered necessary by the Warsaw Pact's offensive capabilities without spurring a further arms race.

However, on 12 December 1979, in light of a build-up of Warsaw Pact nuclear capabilities in Europe, ministers approved the deployment of U.S. Cruise and Pershing II theatre nuclear weapons in Europe. The new warheads were also meant to strengthen the western negotiating position in regard to nuclear disarmament. This policy was called the Dual Track policy. Similarly, in 1983–84, responding to the stationing of Warsaw Pact SS-20 medium-range missiles in Europe, NATO deployed modern Pershing II missiles able to reach Moscow within minutes. This action led to peace movement protests throughout Western Europe.

The membership of the organisation in this time period likewise remained largely static. In 1974, as a consequence of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, Greece withdrew its forces from NATO's military command structure, but, with Turkish cooperation, were readmitted in 1980. On 30 May 1982, NATO gained a new member when, following a referendum, the newly democratic Spain joined the alliance.

In November 1983, NATO manoeuvres simulating a nuclear launch caused panic in the Kremlin. The Soviet leadership, led by ailing General Secretary Yuri Andropov, became concerned that the manoeuvres, codenamed Able Archer 83, were the beginnings of a genuine first strike. In response, Soviet nuclear forces were readied and air units in Eastern Germany and Poland were placed on alert. Though at the time written off by U.S. intelligence as a propaganda effort, many historians now believe that the Soviet fear of a NATO first strike was genuine.

[edit] Cold War stay-behind armies

NATO was founded early in the Cold War with the express aim of defending western Europe against a military invasion by the Soviet Union. On 24 October 1990, Italian Prime minister Giulio Andreotti, a member of the Italian Christian Democracy party, publicly revealed the existence of Gladio, known as "stay-behind armies", clandestine paramilitary militia whose role would be to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines in the case of a successful Warsaw Pact invasion. Andreotti told the Italian Parliament that NATO had long held a covert policy of training partisans in the event of a Soviet invasion of Western Europe.[5][6][7]

Spurred by the difficulties in setting up partisan organisation in occupied Europe during the Second World War, the CIA, British MI6 and NATO trained and armed partisan groups in NATO states to fight a guerrilla war if they were conquered in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion. Operating in all of NATO and even in neutral countries (Austria, Finland - see also Operation Stella Polaris -, Sweden[8] or Switzerland, one of the three states who had a parliamentary inquiry in the matter) or in Spain before its 1982 adhesion to NATO, Gladio was first coordinated by the Clandestine Committee of the Western Union (CCWU), founded in 1948.[9] After the 1949 creation of NATO, the CCWU was integrated into the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC), founded in 1951 and overseen by the SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe), transferred to Belgium after France’s official retreat from NATO in 1966 — which was not followed by the dissolution of the French stay-behind paramilitary movements. According to historian Daniele Ganser, one of the major researcher on the field, "Next to the CPC, a second secret army command centre, labeled Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC), was set up in 1957 on the orders of NATO's Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR). This military structure provided for significant U.S. leverage over the secret stay-behind networks in Western Europe as the SACEUR, throughout NATO's history, has traditionally been a U.S. General who reports to the Pentagon in Washington and is based in NATO's Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Mons, Belgium. The ACC's duties included elaborating on the directives of the network, developing its clandestine capability, and organising bases in Britain and the United States. In wartime, it was to plan stay-behind operations in conjunction with SHAPE. According to former CIA director William Colby, it was 'a major programme'."[9]

The existence of Gladio, one of the best kept secrets of the Cold War, is now widely recognised. Belgium, Italy and Switzerland have held parliamentary inquiries in the matter. What remains controversial is the ties between Gladio members, of whom many belonged to neo-fascist movements, and false flag terrorist attacks. A NATO spokesman denied on 5 November 1990 any knowledge or involvement with Gladio[10] and has since refused to comment.[9] The U.S. State Department has itself admitted the existence of Gladio, but denied it has been involved in terrorism, in particular in Italy and in Greece.[11]

In Italy in particular, Gladio paramilitary groups have been accused by the justice of having carried out dozens of terrorist bombings, which were officially blamed on leftist groups such as the Red Brigades. It has been alleged that these groups and the individuals in them were responsible for the strategy of tension in Italy which aimed at impeding the "historic compromise" between the Christian Democracy and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) (including the 1969 Piazza Fontana bombing and the Bologna massacre (1980))[12][13][9] political assassinations in Belgium,[14] military coups in Greece (1967) and Turkey (1980)[15] and an attempted coup in France (1961).[16] The supposed aim of this group was to prevent Communist movements in Western Europe from gaining power. Some researchers have said that the true aim was to increase the power and control of the United States over Europe.[9][17][18][9]

In 2000, a report from the Italian Left Democrat party, "Gruppo Democratici di Sinistra l'Ulivo", concluded that the strategy of tension had been supported by the United States to "stop the PCI (Communist Party), and to a certain degree also the PSI (Socialist Party), from reaching executive power in the country". A report, stated that "Those massacres, those bombs, those military actions had been organised or promoted or supported by men inside Italian state institutions and, as has been discovered more recently, by men linked to the structures of United States intelligence."[19][20]

[edit] Post-Cold War

The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991 removed the de facto main adversary of NATO. This caused a strategic re-evaluation of NATO's purpose, nature and tasks. In practice this ended up entailing a gradual (and still ongoing) expansion of NATO to Eastern Europe, as well as the extension of its activities to areas that had not formerly been NATO concerns. The first post-Cold War expansion of NATO came with the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, when the former East Germany became part of the Federal Republic of Germany and the alliance. This had been agreed in the Two Plus Four Treaty earlier in the year. To secure Soviet approval of a united Germany remaining in NATO, it was agreed that foreign troops and nuclear weapons would not be stationed in the east, and also that NATO would never expand further east.[21]

On 28 February 1994, NATO also took its first military action, shooting down four Bosnian Serb aircraft violating a U.N.-mandated no-fly zone over central Bosnia and Herzegovina. Operation Deny Flight, the no-fly-zone enforcement mission, had began a year before, on 12 April 1993, and was to continue until 20 December 1995. NATO air strikes that year helped bring the war in Bosnia to an end, resulting in the Dayton Agreement.

Between 1994 and 1997, wider forums for regional cooperation between NATO and its neighbours were set up, like the Partnership for Peace, the Mediterranean Dialogue initiative and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council. On 8 July 1997, three former communist countries, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, were invited to join NATO, which finally happened in 1999.

On 24 March 1999, NATO saw its first broad-scale military engagement in the Kosovo War, where it waged an 11-week bombing campaign against what was then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. A formal declaration of war never took place. Yugoslavia referred to the Kosovo War as military aggression, as being undeclared and contravening the UN Charter.[22] The conflict ended on 11 June 1999, when Yugoslavian leader Slobodan Milošević agreed to NATO’s demands by accepting UN resolution 1244. NATO then helped establish the KFOR, a NATO-led force under a United Nations mandate that operated the military mission in Kosovo.

Debate concerning NATO's role and the concerns of the wider international community continued throughout its expanded military activities: The United States opposed efforts to require the U.N. Security Council to approve NATO military strikes, such as the ongoing action against Yugoslavia, while France and other NATO countries claimed the alliance needed U.N. approval. American officials said that this would undermine the authority of the alliance, and they noted that Russia and China would have exercised their Security Council vetoes to block the strike on Yugoslavia. In April 1999, at the Washington summit, a German proposal that NATO adopt a no-first-use nuclear strategy was rejected.

[edit] After the September 11 attacks

The expansion of the activities and geographical reach of NATO grew even further as an outcome of the September 11 attacks. These caused as a response the provisional invocation (on September 12) of the collective security of NATO's charter—Article 5 which states that any attack on a member state will be considered an attack against the entire group of members. The invocation was confirmed on 4 October 2001 when NATO determined that the attacks were indeed eligible under the terms of the North Atlantic Treaty.[23] The eight official actions taken by NATO in response to the attacks included the first two examples of military action taken in response to an invocation of Article 5: Operation Eagle Assist and Operation Active Endeavour.

Despite this early show of solidarity, NATO faced a crisis little more than a year later, when on 10 February 2003, France and Belgium vetoed the procedure of silent approval concerning the timing of protective measures for Turkey in case of a possible war with Iraq. Germany did not use its right to break the procedure but said it supported the veto.

On the issue of Afghanistan on the other hand, the alliance showed greater unity: On 16 April 2003 NATO agreed to take command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. The decision came at the request of Germany and the Netherlands, the two nations leading ISAF at the time of the agreement, and all 19 NATO ambassadors approved it unanimously. The handover of control to NATO took place on 11 August, and marked the first time in NATO’s history that it took charge of a mission outside the north Atlantic area. Canada had originally been slated to take over ISAF by itself on that date.

In January 2004, NATO appointed Minister Hikmet Çetin, of Turkey, as the Senior Civilian Representative (SCR) in Afghanistan. Minister Cetin is primarily responsible for advancing the political-military aspects of the Alliance in Afghanistan.

On 31 July 2006, a NATO-led force, made up mostly of troops from Canada, Great Britain, Turkey and the Netherlands, took over military operations in the south of Afghanistan from a U.S.-led anti-terrorism coalition.

[edit] Expansion and restructuring

New NATO structures were also formed while old ones were abolished: The NATO Response Force (NRF) was launched at the 2002 Prague Summit on 21 November. On 19 June 2003, a major restructuring of the NATO military commands began as the Headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Atlantic were abolished and a new command, Allied Command Transformation (ACT), was established in Norfolk, Virginia, USA, and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) became the Headquarters of Allied Command Operations (ACO). ACT is responsible for driving transformation (future capabilities) in NATO, whilst ACO is responsible for current operations.

Membership went on expanding with the accession of seven more Northern European and Eastern European countries to NATO: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (see Baltic Air Policing) and also Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania. They were first invited to start talks of membership during the 2002 Prague Summit, and joined NATO on 29 March 2004, shortly before the 2004 Istanbul Summit.

A number of other countries have also expressed a wish to join the alliance, including Albania, Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Georgia, Montenegro and Ukraine.

From the Russian point of view, NATO's eastward expansion since the end of the Cold War has been in clear breach of an agreement between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President George H. W. Bush which allowed for a peaceful unification of Germany. NATO's expansion policy is seen as a continuation of a Cold War attempt to surround and isolate Russia.[24][25][26][27]

The 2006 NATO summit was held in Riga, Latvia, which had joined the Atlantic Alliance two years earlier. It is the first NATO summit to be held in a country that was part of the Soviet Union, and the second one in a former COMECON country (after the 2002 Prague Summit). Energy Security was one of the main themes of the Riga Summit. [28]

[edit] ISAF

In August 2003, NATO commenced its first mission ever outside Europe when it assumed control over International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. However, some critics feel that national caveats or other restrictions undermine the efficiency of ISAF. For instance, political scientist Joseph Nye stated in a 2006 article that "many NATO countries with troops in Afghanistan have "national caveats" that restrict how their troops may be used. While the Riga summit relaxed some of these caveats to allow assistance to allies in dire circumstances, Britain, Canada, the Netherlands, and the U.S. are doing most of the fighting in southern Afghanistan, while French, German, and Italian troops are deployed in the quieter north. At the hands of the escalation of the fighting, France has recently accepted to redeploy its bombers in the south to help the other countries[29]. It is difficult to see how NATO can succeed in stabilising Afghanistan unless it is willing to commit more troops and give commanders more flexibility."[30] If these caveats were to be eliminated, it is argued that this could help NATO to succeed.

[edit] NATO missile defence talks controversy

For some years, the United States negotiated with Poland and the Czech Republic for the deployment of interceptor missiles and a radar tracking system in the two countries. Both countries' governments indicated that they would allow the deployment. The proposed American missile defence site in Central Europe is believed to be fully operational in 2015 and would be capable of covering most of Europe except part of Romania plus Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey.[31]

In April 2007, NATO's European allies called for a NATO missile defence system which would complement the American National Missile Defense system to protect Europe from missile attacks and NATO's decision-making North Atlantic Council held consultations on missile defence in the first meeting on the topic at such a senior level.[31]

In response, Russian president Vladimir Putin claimed that such a deployment could lead to a new arms race and could enhance the likelihood of mutual destruction. He also suggested that his country should freeze its compliance with the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) - which limits military deployments across the continent - until all NATO countries had ratified the adapted CFE treaty.[32]

Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer said the system would not affect strategic balance or threaten Russia, as the plan is to base only 10 interceptor missiles in Poland with an associated radar in the Czech Republic.[33]

On July 14, Russia notified its intention to suspend the CFE treaty, effective 150 days later.

[edit] Membership

There are currently 26 members within NATO.

| Date | Country | Expansion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 4, 1949 | Founders | ||

| France withdrew from the integrated military command in 1966. From then until 1993 it had remained solely a member of NATO's political structure. | |||

| Iceland, the sole member that does not have its own standing army, joined on the condition that they would not be expected to establish one. However, it has a Coast Guard and has recently provided troops trained in Norway for NATO peacekeeping. | |||

| 18 February 1952 | First | Greece withdrew its forces from NATO’s military command structure from 1974 to 1980 as a result of Greco-Turkish tensions following the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus. | |

| 9 May 1955 | Second | (as West Germany; Saarland reunited with it in 1957 and the territory of the former German Democratic Republic reunited with it on 3 October 1990) | |

| 30 May 1982 | Third | ||

| 12 March 1999 | Fourth | ||

| 29 March 2004 | Fifth | ||

[edit] Future membership

Article X of the North Atlantic Treaty makes it possible that non-member states join NATO:[34]

| “ | The Parties may, by unanimous agreement, invite any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area to accede to this Treaty. Any State so invited may become a Party to the Treaty by depositing its instrument of accession with the Government of the United States of America. The Government of the United States of America will inform each of the Parties of the deposit of each such instrument of accession. | ” |

Note that this article poses two general limits to non-member states: (1) only European states are eligible for membership and (2) these states need the approval of all the existing member states. The second criterion means that every member state can put some criteria forward that have to be attained. In practice, NATO formulates in most cases a common set of criteria, but for instance in the case of Cyprus, Turkey blocks Cyprus' wish to be able to apply for membership as long as the Cyprus dispute is not resolved.

[edit] Membership Action Plan

As a procedure for nations wishing to join NATO, a mechanism called Membership Action Plan (MAP) was approved in the Washington Summit of 1999. A country's participation in MAP entails the annual presentation of reports concerning its progress on five different measures:

- Willingness to settle international, ethnic or external territorial disputes by peaceful means, commitment to the rule of law and human rights, and democratic control of armed forces

- Ability to contribute to the organisation's defence and missions

- Devotion of sufficient resources to armed forces to be able to meet the commitments of membership

- Security of sensitive information, and safeguards ensuring it

- Compatibility of domestic legislation with NATO cooperation

NATO provides feedback as well as technical advice to each country and evaluates its progress on an individual basis.[35]

NATO is also unlikely to invite countries such as the Republic of Ireland, Sweden, Finland, Austria and Switzerland, where popular opinions do not support NATO membership. NATO officially recognises the policy of neutrality practised in these countries, and does not consider the failure to set a goal for NATO membership as a sign of distrust.

| Country | Partnership for Peace | Individual Partnership Action Plan | NATO membership declared as goal | Intensified Dialogue | Membership Action Plan | NATO membership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 1994 | - | - | April 1999 | Expected April 2008[36] | ||

| May 2000 | - | - | May 2002 | Expected April 2008[citation needed] | ||

| November 1995 | - | - | April 1999 | Expected April 2008[citation needed] | ||

| March 1994 | October 2004 | September 2006[37] | Expected April 2008 | Expected 2010 | ||

| December 2006 | - | - | Expected April 2010 | Expected 2012 [citation needed] |

||

| December 2006 | - | - | Expected April 2010 | Expected 2012 | ||

| December 2006 | (exp.2008)[38] | - | - | - | ||

| February 1994 | - | April 2005 | - | - | ||

| May 1994 | May 2005 | -[39] | - | - | - | |

| October 1994 | December 2005 | - | - | - | ||

| May 1994 | January 2006 | - | - | - | ||

| March 1994 | May 2006 | - | - | - | - | |

| May 1994 | - | - | - | - | ||

| May 1994 | - | - | - | - | ||

| May 1994 | - | - | - | - | ||

| June 1994 | - | - | - | - | ||

| June 1994 | - | - | - | - | ||

| July 1994 | - | - | - | - | ||

| January 1995 | - | - | - | - | ||

| February 1995 | - | - | - | - | ||

| December 1996 | - | - | - | - | ||

| December 1999 | - | - | - | - | ||

| February 2002 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Pending resolution of the Cyprus dispute | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Former signatory, 1995–1996 | - | - | - | - |

[edit] Debate about membership

[edit] Croatia

The Croatian government considers NATO membership a top priority,[41] and a 2003 opinion poll showed that about 60% of the Croatian citizens were in favor of NATO membership.[42] Support for membership declined after 2003, was only 29% in 2006, but resurged during 2007.[43][41] It is not yet known how Croatia will make the final decision about membership: through an act of parliament or via a binding referendum, but on 23 March 2007, Croatian president Stjepan Mesić, prime minister Ivo Sanader and president of parliament Vladimir Šeks declared that there is no need for a referendum, because they are convinced that the Croatian population supports entry to NATO.[44] Earlier, in 2006, the Croatian government was planning a public campaign to promote the benefits of membership. A May 2007 poll conducted by the government shows growing support for NATO membership as 52% of the population (up 9% from March) supports membership and only 25% are against.[45]

Recently, it was made public that a Slovenian military air base in Cerklje ob Krki, near the Croatian border would be transformed in a NATO base. In 2010 the base would become operational and it is expected that the military planes of this base will have to use Croatian air space [46]. Local inhabitants and environmentalists from both sides of the border are expressing their concerns about this base.

[edit] Finland

Finland is participating in nearly all sub-areas of the Partnership for Peace programme, and has provided peacekeeping forces to the Afghanistan and Kosovo missions. Polls in Finland indicate that the public is strongly against NATO membership[47] and the possibility of Finland's membership in NATO was one of the most major issues debated in relation to the Finnish presidential election of 2006.

The main contester of the presidency, Sauli Niinistö of the National Coalition Party, supported Finland joining a "more European" NATO. Fellow right-winger Henrik Lax of the Swedish People's Party likewise supported the concept. On the other side, president Tarja Halonen of the Social Democratic Party opposed changing the status quo, as did most other candidates in the election. Her victory and re-election to the post of president has currently put the issue of a NATO membership for Finland on hold for at least the duration of her term. Finland could however change its official position on NATO membership after the new E.U. treaty clarifies if there will be any new E.U.–level defence deal, but in the meantime Helsinki's defence ministry is pushing to join NATO and its army is making technical preparations for membership[48], stating that it would increase Finland's security.[49]

Other political figures of Finland who have weighed in with opinions include former President of Finland Martti Ahtisaari who has argued that Finland should join all the organisations supported by other Western democracies in order "to shrug off once and for all the burden of Finlandisation".[50] An ex-president, Mauno Koivisto, opposes the idea, arguing that NATO membership would ruin Finland's relations with Russia.[51]

[edit] Serbia

During the 2006 Riga Summit Serbia joined the PFP programme. While this programme is often the first step towards full NATO membership, it is uncertain whether Serbia perceives it an intent to join the alliance[52] (NATO fought Bosnian-Serbian forces during the Bosnia war and Serbia during the 1999 Kosovo conflict). An overwhelming Serbian majority opposes NATO membership.[52] Recently the DS party of Serbia which is seen as overwhelmingly pro-EU has given hints that it is also wished to integrate the country into NATO. Although they remain silent on the issue most of the time (so as not to lose popularity) it is facing a problem from its coalition partners DSS and NS which are diametrically opposed to NATO membership. Recently these parties have begun verbal attacks on NATO for its presence in the Serbian province of Kosovo accusing them of establishing a NATO state, governed from Camp Bondsteel[53]. As of now Serbia does not intend to join NATO and the idea has been shelved as a low priority in the Serbian governments plans.[citation needed]

Unofficially a poll has not been taken to see just how many people in Serbia are in support for NATO, some believe this to be deliberate, choosing to "not know" how many people would voice their "support".[citation needed] The DS party is taking an incredible risk to its popularity in the case of supporting NATO membership. Its confrontation with DSS will directly affect the two party's popularity.[citation needed] The Serbian Ministry of Defense and the Serbian President are both from the DS party while the Prime Minister is of the DSS.

[edit] Sweden

In 1949 Sweden elected[citation needed] not to join NATO and declared a security policy aiming for: non-alignment in peace, neutrality in war. A modified version now states: non-alignment in peace for possible neutrality in war. This position was maintained without much discussion during the Cold War. Since the 1990s however there has been an active debate in Sweden on the question of NATO membership in the post-Cold War world.[citation needed] While the governing parties in Sweden have opposed membership, they have participated in NATO-led missions in Bosnia (IFOR and SFOR), Kosovo (KFOR) and Afghanistan (ISAF).

The Swedish Centre Party and Social Democratic party have remained in favour of non-alignment. This view is shared by Green and Left parties in Sweden. The Moderate Party and the Liberal party lean toward NATO membership.[citation needed]

These ideological cleavages were visible again in November 2006 when Sweden could either buy two new transport planes or join NATO's plane pool,[54] and in December 2006, when Sweden was invited to join the NATO Response Force.[55]

A 2005 poll indicated that more Swedes were opposed to NATO membership than there were supporters (46% against, 22% for).[56]

[edit] Ukraine

Ukraine Defence Minister Anatoliy Hrytsenko declared that Ukraine would have an Action Plan on NATO membership by the end of March 2006, to begin implementation by September 2006. A final decision concerning Ukraine's membership in NATO is expected to be made in 2008, with full membership possible by 2010.[57]

The idea of Ukrainian membership in NATO has gained support from a number of NATO leaders, including President Traian Băsescu of Romania[58] and president Ivan Gašparovič of Slovakia.[59] The Deputy Foreign Minister of Russia, Alexander Grushko, announced however that NATO membership for Ukraine was not in Russia's best interests and wouldn't help the relations of the two countries.[60]

Currently a majority of Ukrainian citizens oppose NATO membership, independently of their respective political views and beliefs[citation needed]. Protests have taken place by opposition blocs against the idea, and petitions signed urging the end of relations with NATO. Former Prime Minister Yuriy Yekhanurov has indicated Ukraine will not enter NATO as long as the public continues opposing the move.[61] Plans for membership were shelved on 14 September 2006 due to the overwhelming disapproval of NATO membership.[62] Currently the Ukrainian Government started an information campaign, aimed at informing the Ukrainian people about the consequences of membership. The likelihood of a referendum regarding membership is growing.[citation needed]

[edit] Cooperation with non-member states

[edit] Euro-Atlantic Partnership

A double framework has been established to help further co-operation between the 26 NATO members and 23 "partner countries".

- The Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme was established in 1994 and is based on individual bilateral relations between each partner country and NATO: each country may choose the extent of its participation. The PfP programme is considered the operational wing of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership.[63]

- The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) on the other hand was first established on 29 May 1997, and is a forum for regular coordination, consultation and dialogue between all 49 participants.[64]

The 23 partner countries are the following:

|

Malta joined PfP in 1994, but its new government withdrew in 1996. Because of this Malta is not participating in E.S.D.P. activities that use NATO assets and information.

Malta joined PfP in 1994, but its new government withdrew in 1996. Because of this Malta is not participating in E.S.D.P. activities that use NATO assets and information. Cyprus's admission to PfP is resisted by Turkey, because of the Northern Cyprus issue. Because of this Cyprus is not participating in ESDP activities that use NATO assets and information.

Cyprus's admission to PfP is resisted by Turkey, because of the Northern Cyprus issue. Because of this Cyprus is not participating in ESDP activities that use NATO assets and information.

[edit] Individual Partnership Action Plans

Launched at the November 2002 Prague Summit, Individual Partnership Action Plans (IPAPs) are open to countries that have the political will and ability to deepen their relationship with NATO.[65]

Currently IPAPs are in implementation with the following countries:

Georgia (29 October 2004)

Georgia (29 October 2004) Azerbaijan (27 May 2005)

Azerbaijan (27 May 2005) Armenia (16 December 2005)

Armenia (16 December 2005) Kazakhstan (31 January 2006)

Kazakhstan (31 January 2006) Moldova (19 May 2006)

Moldova (19 May 2006)

[edit] Intensified Dialogue

Intensified Dialogue with NATO is viewed as a stage before being invited to enter the alliance Membership Action Plan (MAP), while the latter should eventually lead to NATO membership.

Countries currently engaged in an Intensified Dialogue with NATO:

[edit] Mediterranean Dialogue

The Mediterranean Dialogue, first launched in 1994 is a forum of cooperation between NATO and seven countries of the Mediterranean:[66]

On 16 October 2006, NATO and Israel finalised the first ever Individual Cooperation Programme (ICP) under the enhanced Mediterranean Dialogue, where Israel will be contributing to the NATO maritime Operation Active Endeavour.[67] The ICP covers many areas of common interest, such as the fight against terrorism and joint military exercises in the Mediterranean Sea.

[edit] NATO-Russian Federation Council

NATO and the Russian Federation made a reciprocal commitment in 1997 "to work together to build a stable, secure and undivided continent on the basis of partnership and common interest."

In May 2002, this commitment was strengthened with the establishment of the NATO-Russia Council, which brings together the NATO members and the Russian Federation. The purpose of this council is to identify and pursue opportunities for joint action with the 27 participants as equal partners.

[edit] Other partners

The Philippines has been a longstanding ally and friend of the U.S. The Philippines was designated a Major Non-NATO Ally on October 6, 2003 to allow the U.S. and the Philippines to work together on military research and development. In April 2005, Australia, which had been appointed a U.S. Major non-NATO ally (MNA) in 1989, signed a security agreement with NATO on enhancing intelligence co-operation in the fight against terrorism. Australia also posted a defence attache to NATO's headquarters.[68] Cooperation with Japan (MNA, 1989), El Salvador, South Korea (MNA, 1989) and New Zealand (MNA, 1996) was also announced as priority.[69] Israel (MNA, 1989) is currently a Mediterranean Dialogue country and has been recently seeking to expand its relationship with NATO. The first visit by a head of NATO to Israel occurred on 23 February - 24 February 2005[70] and the first joint Israel-NATO naval exercise occurred on 27 March 2005.[71] In May of the same year Israel was admitted to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. Israeli troops also took part in NATO exercises in June 2005.

There have been advocates for the NATO membership of Israel, amongst them the former Prime Minister of Spain José María Aznar and Italian Defence Minister Antonio Martino. However Secretary-General of the organisation Jaap de Hoop Scheffer has dismissed such calls, saying that membership for Israel is not on the table. Martino himself said that a membership process could only come after an Israeli request; such a request has not taken place.[72]

Israeli Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom stated in February 2005 that his country was looking to upgrade its relationship with NATO from a dialogue to a partnership, but that it was not seeking membership, saying that "NATO members are committed to mutual defence and we don't think we are in a position where we can intervene in other struggles in the world", and also that "We don't see that NATO should get engaged in our conflict here in the Middle East."[73]

The issue of Israel's potential membership again came to the forefront in early 2006 after heightened tensions between Israel and Iran. Former Prime Minister of Spain José María Aznar argued that Israel should become a member of the organisation alongside Japan and Australia, saying that "So far, expansion of NATO was an attempt at the growth and consolidation of democratic change in the former communist countries. Now it is time to do the opposite, to expand toward those democratic nations that are committed to the struggle against our common enemy and ready to contribute to the common effort to free ourselves from it."[74][75]

Aznar also proposed a strategic co-operation with India and Colombia.

[edit] Structures

[edit] Political structure

Like any alliance, NATO is ultimately governed by its 26 member states. However, the North Atlantic Treaty, and other agreements, outline how decisions are to be made within NATO. Each of the 26 members sends a delegation or mission to NATO’s headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.[76] The senior permanent member of each delegation is known as the Permanent Representative and is generally a senior civil servant or an experienced ambassador (and holding that diplomatic rank).

Together the Permanent Members form the North Atlantic Council (NAC), a body which meets together at least once a week and has effective political authority and powers of decision in NATO. From time to time the Council also meets at higher levels involving Foreign Ministers, Defence Ministers or Heads of State or Government (HOSG) and it is at these meetings that major decisions regarding NATO’s policies are generally taken. However, it is worth noting that the Council has the same authority and powers of decision-making, and its decisions have the same status and validity, at whatever level it meets.

The meetings of the North Atlantic Council are chaired by the Secretary General of NATO and, when decisions have to be made, action is agreed upon on the basis of unanimity and common accord. There is no voting or decision by majority. Each nation represented at the Council table or on any of its subordinate committees retains complete sovereignty and responsibility for its own decisions.

The second pivotal member of each country's delegation is the Military Representative, a senior officer from each country's armed forces. Together the Military Representatives form the Military Committee (MC), a body responsible for recommending to NATO’s political authorities those measures considered necessary for the common defence of the NATO area. Its principal role is to provide direction and advice on military policy and strategy. It provides guidance on military matters to the NATO Strategic Commanders, whose representatives attend its meetings, and is responsible for the overall conduct of the military affairs of the Alliance under the authority of the Council. Like the council, from time to time the Military Committee also meets at a higher level, namely at the level of Chiefs of defence, the most senior military officer in each nation's armed forces. The Defence Planning Committee excludes France, due to that country's 1966 decision to remove itself from NATO's integrated military structure.[77] On a practical level, this means that issues that are acceptable to most NATO members but unacceptable to France may be directed to the Defence Planning Committee for more expedient resolution. Such was the case in the lead up to Operation Iraqi Freedom.[78] []

The current Chairman of the NATO Military Committee is Ray Henault of Canada (since 2005).

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly, presided by José Lello, is made up of legislators from the member countries of the North Atlantic Alliance as well as 13 associate members.[79] It is however officially a different structure from NATO, and has as aim to join together deputies of NATO countries in order to discuss security policies.

[edit] List of officials

| 1 | General Lord Ismay | 4 April 1952 – 16 May 1957 | |

| 2 | Paul-Henri Spaak | 16 May 1957 – 21 April 1961 | |

| 3 | Dirk Stikker | 21 April 1961 – 1 August 1964 | |

| 4 | Manlio Brosio | 1 August 1964 – 1 October 1971 | |

| 5 | Joseph Luns | 1 October 1971 – 25 June 1984 | |

| 6 | Lord Carrington | 25 June 1984 – 1 July 1988 | |

| 7 | Manfred Wörner | 1 July 1988 – 13 August 1994 | |

| 8 | Sergio Balanzino | 13 August 1994 – 17 October 1994 | |

| 9 | Willy Claes | 17 October 1994 – 20 October 1995 | |

| 10 | Sergio Balanzino | 20 October 1995 – 5 December 1995 | |

| 11 | Javier Solana | 5 December 1995 – 6 October 1999 | |

| 12 | Lord Robertson of Port Ellen | 14 October 1999 – 1 January 2004 | |

| 13 | Jaap de Hoop Scheffer | 1 January 2004 – present |

| # | Name | Country | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sergio Balanzino | 1994 – 2001 | |

| 2 | Alessandro Minuto Rizzo | 2001 – present |

[edit] Military structure

NATO’s military operations are directed by two Strategic Commanders, both senior U.S. officers assisted by a staff drawn from across NATO. The Strategic Commanders are responsible to the Military Committee for the overall direction and conduct of all Alliance military matters within their areas of command.

Before 2003 the Strategic Commanders were the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) but the current arrangement is to separate command responsibility between Allied Command Transformation (ACT), responsible for transformation and training of NATO forces, and Allied Command Operations, responsible for NATO operations world wide.

The commander of Allied Command Operations retained the title "Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR)", and is based in the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) located at Casteau, north of the Belgian city of Mons. This is about 80 km (50 miles) south of NATO’s political headquarters in Brussels. Allied Command Transformation (ACT) is based in the former Allied Command Atlantic headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia, USA.

[edit] NATO bases worldwide

Further information: Category:Military facilities of NATO

The NATO structure is divided into two commands, one for operations and one for transformation. Allied Command Operations (ACO), on one hand, is based at SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe), located at Casteau, north of Mons in Belgium. The ACO is headed by SACEUR, a U.S. four star general with the dual-hatted role of heading U.S. European Command, which is headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany. SHAPE was in Paris until 1966, when French president Charles de Gaulle withdrew French forces from the Atlantic Alliance. NATO's headquarters were then forced to move to Belgium, while many military units had to move. During a large-scale relocation plan, Operation Freloc, USAFE presence in the U.K. greatly increased.

On the other hand, Allied Command Transformation (ACT) is located in Norfolk, Virginia, at the former headquarters of SACLANT (Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic, decommissioned in 2003) and headed by the Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (SACT), a U.S. four-star general or admiral with the dual-hatted role as commander U.S. Joint Forces Command (COMUSJFCOM). It the ACT is co-located in the United States Joint Forces Command in Norfolk, Virginia, there is also an ACT command element located at SHAPE in Mons, Belgium. Additional command elements include the Joint Warfare Centre (JWC) located in Stavanger, Norway (in the same site as the Norwegian NJHQ); the Joint Force Training Centre (JFTC) in Bydgoszcz, Poland; the Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre (JALLC) in Monsanto, Portugal; and the NATO Undersea Research Centre (NURC), La Spezia, Italy. These additional elements assist in ACT's transformation efforts. Under a customer-funded arrangement, ACT invests about 30 million Euros into research with the NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A) each year to support scientific and experimental programmes.

The existence and ownership, or simple use via leasing, of military bases is subject to domestic and international changes in political context. Some bases used by allied countries members of NATO are not NATO bases, but may be national or joint bases. The US have bases scattered all over the world, which may sometimes be used by allies (e.g. Spanish Morón Air Base was used by NATO during the 1999 Kosovo War). Since the end of the Cold War, the US have closed many bases, implementing Base Realignment and Closure plans, the latest being the 2005 plan. However, others bases are opened, and readjustments always occurring (i.e. transfer of planes from the Spanish Torrejon Air Base to the Italian Aviano Air Base, etc.).

Beginning in 1953 USAFE (US Air Forces in Europe) NATO Dispersed Operating Bases were constructed in France and were completed in about two years. Each was built to a standard NATO design of a 7,900 foot (2,408 m) runway. Four DOBs were built for USAFE use. They were designed to have the capability to base about 30 aircraft, along with a few permanent buildings serviced with utilities and space for a tent city to house personnel. Between 1950 and 1967, when all NATO forces had to withdraw from France, the USAFE operated ten major air bases in France.

[edit] Bases in Germany

- Further information: List of United States Army installations in Germany

The USAFE (United States Air Forces in Europe)'s headquarters are located in Ramstein Air Base (West Germany), after having been relocated from Wiesbaden Army Airfield in 1973. Sembach Air Base, used by NATO during the Cold War, was returned to German control and became an annexe of Ramstein Air Base in 1995. USAFE also maintains another base in Germany called Spangdahlem Air Base, The 52nd Fighter Wing the base's host wing maintains, deploys and employs F-16CJ and A/OA-10 aircraft and TPS-75 radar systems in support of NATO and the national defence directives. The wing supports the Supreme Allied Commander Europe with mission-ready personnel and systems providing expeditionary air power for suppression of enemy air defences, close air support, air interdiction, counterair, air strike control, strategic attack, combat search and rescue, and theater airspace control. The wing also supports contingencies and operations other than war as required. Germany also hosts the Campbell Barracks in Heidelberg, Germany, which is the location of the Headquarters of the US Army in Europe and Seventh Army (HQ USAREUR, /7A, as well as V Corps and the headquarters of NATO’s Allied Land Component Command, Heidelberg, (CC-Land Heidelberg). The Kaiserslautern Military Community is the largest U.S. military community outside of the U.S., while the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center is the largest U.S. military hospital overseas, treating wounded soldiers from Iraq or Afghanistan. Furthermore, Patch Barracks is home to the U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and is the headquarters for U.S. armed forces in Europe. It is also the centre for the Special Operations Command, Europe (SOCEUR), which commands all US special forces units in Europe. NATO also operates a fleet of E-3A Sentry AWACS airborne radar aircraft based at Geilenkirchen Air Base in Germany, and is establishing the NATO Strategic Airlift Capability through the planned purchase of a number of C-17s.

[edit] Bases in Italy

- Further information: List of United States military bases in Italy

NATO's Naval Forces' headquarters will be relocated from London to Napoli (Italy), where NATO's Joint Force Command (headed by a U.S. admiral) is also based. The Naval Air Station Sigonella, in Sicily, is one of the most frequently used stops for U.S. airlifters bound from the continental United States to Southwest Asia and the Indian Ocean. In the nort-east of Italy, Aviano Air Base (used for the Imam Rapito extraordinary rendition case) is the HQ of the 31st Fighter Wing which conducts and supports air operations in Europe's southern region and to maintain munitions for the NATO and national authorities. Aviano Air Base was brought into NATO after a 1954 US-Italian agreement, and received F-16 planes from Torrejon Air Base after its closure in the 1990s. San Vito dei Normanni Air Station, also used as a U.S. naval base, hosted a FLR-9 receiving system for COMINT intelligence purposes from 1964 to 1994. It hosts now the 691th Electronic Security Group and other assigned U.S. and NATO units. NATO also inaugurated a new base in 2004 in Chiapparo nel Mar Grande (Taranto)[81] The enlargement of the Caserma Ederle in Vicenza, planned for 2007 and accepted by Silvio Berlusconi's government, caused some opposition from Romano Prodi's government, although it finally accepted the relocation.[82] Between 40,000 to 100,000 Italians marched against this extension project on 17 February, 2007[83]

[edit] Bases in Spain

- Further information: US-Spanish joint military bases

Torrejon Air Base, near Madrid in Spain, was the headquarters of the United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) Sixteenth Air Force as well as the 401st Tactical Fighter Wing. However, under popular discontent in particular from the PSOE and the PCE, an agreement was reached in 1988 to reduce U.S. military presence in Spain. Henceforth, aircraft (mostly F-16) based at Torrejon were rotated to other USAFE airbases at Aviano Air Base, Italy, and at Incirlik AB, Turkey. Torrejon was, in addition, a staging, reinforcement, and logistical airlift base. The USAFE completely withdrew its forces on 21 May, 1992.

Morón Air Base, near Seville, became in 1992 the home of the US 92d Air Refueling Wing, which was tasked with providing fuel to NATO forces during the 1999 bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Morón Air Base was the largest tanker base during the Kosovo War

As of 2007, Zaragossa is expected to host the new Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) system of NATO, produced by the Transatlantic Industrial Proposed Solution (TIPS) consortium with the goal of having an initial operational capability in 2010.[84] As in Italy, this has been met with some opposition from various anti-militarist sectors of Spanish society.[85]

[edit] Others

The SHAPE Technical Centre (STC) in The Hague (Netherlands) merged in 1996 with the NATO Communications and Information Systems Agency (NACISA) based in Brussels (Belgium), forming the NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A). The agency comprises around 650 staff, of which around 400 are located in The Hague and 250 in Brussels. It reports to the NATO Consultation, Command and Control Board (NC3B).

NATO's Joint Force Command Brunssum (Netherlands) houses members of the central European NATO countries, but includes the US armed forces, Canadian forces, British, German, Belgian and Dutch personnel.

In the Portuguese territory of the Azores, the Lajes Field provides support to 3,000 aircraft including fighters from the U.S. and 20 other allied nations each year. The geographic position has made this airbase strategically important to both American and NATO's warfighting capability. Beginning in 1997, large fighter aircraft movements called Air Expeditionary Forces filled the Lajes flightline. Lajes also has hosted B-52 and B-1 bomber aircraft on global air missions. Lajes also supports many routine NATO exercises, such as the biennial Northern Viking exercise.

In Netherlands the Soesterberg Air Base, used by the USAFE, was closed after the Cold War, and the 298 and 300 300 Squadron are to be moved to Gilze-Rijen Air Base. The Leeuwarden Air Base is the home of the annual NATO exercise "Frisian Flag".

U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has signed the Defense Cooperation Agreement with Sofia (Bulgaria), a new NATO member, in 2006. The treaty allows the US (not NATO) to develop as joint U.S.-Bulgarian facilities the Bulgarian air bases at Bezmer (near Yambol) and Graf Ignatievo (near Plovdiv), the Novo Selo training range (near Sliven), and a logistics centre in Aytos, as well as to use the commercial port of Burgas. At least 2,500 U.S. personnel will be located there. The treaty also allows the U.S. to use the bases "for missions in tiers country without a specific authorisation from Bulgarian authorities," and grants U.S. militaries immunity from prosecution in this country.[86] Another agreement with Romania permits the U.S. to use the Mihail Kogălniceanu base and another one nearby.[86]

Various military bases are used in Turkey, including the Incirlik Air Base, near Adana, and İzmir Air Base. The U.S. 39th Air Base Wing, located at Incirlik since 1966, recently took part in Operation Northern Watch, a U.S. European Command Combined Task Force (CTF) charged with enforcing its own no-fly zone above the 36th parallel in Iraq, which started in January 1997. It also took part in the 2001 invasion of Aghanistan and in the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In Serbia province Kosovo, Camp Bondsteel serves as the NATO headquarters for KFOR's Multinational Task Force East (MNTF-E). Camp Monteith has also been used by the KFOR.

Camp Arifjan, a US Army base in Kuwait, has hosted various soldiers from allied countries. Manas Air Base in Kyrgyzstan, owned by the US Air Force, has also been used by the French Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force during (non-NATO) Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. Although NATO was not initially engaged in Afghanistan, it has since deployed the ISAF force, which took control of the country in October 2006.

Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who succeeded to Askar Akayev after the 2005 Tulip Revolution, threatened in April 2006 to expel U.S. troops from the base if the United States didn't agree by June 1 to pay more for stationing forces in the Central Asian nation. However, he finally withdrew this threat, but the U.S. and Kyrgyzstan have yet to agree to new terms for the military base. Beside the U.S. and NATO, others global powers such as Russia and China are trying to acquire bases in Central Asia, in a struggle dubbed the "New Great Game." Thus, President of Uzbekistan Islom Karimov ordered the US to leave the Karshi-Khanabad which was vacated in January 2006.

In Djibouti, NATO owns no bases, but both France and the U.S. (since 2002) are present, with the 13th Foreign Legion Demi-Brigade sharing Camp Lemonier with the Combined Joint Task Force Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) of the United States Central Command. It is from Djibouti that Abu Ali al-Harithi, suspected mastermind of the 2000 USS Cole bombing, and U.S. citizen Ahmed Hijazi, along with four others persons, were assassinated in 2002 while riding a car in Yemen, by a Hellfire missile sent by a RQ-1 Predator drone actionned from CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.[87] It is also from there that the U.S. Army launched attacks in 2007 against Islamic forces in Somalia.

As NATO does not share a common intelligence interception system, each country develops its installations on its own. However, English-speaking countries members of the UKUSA Community have joined in the ECHELON programme, which has bases scattered around the world. France allegedly has developed its own interception system, nicknamed "Frenchelon," as did Switzerland with the Onyx interception system (which recently gave the proof of the existence of CIA-operated black sites in Europe).

[edit] Equipment

Most of NATO's military hardware belongs to member nations and bears the names of the respective members. Ground forces have repainted some of their vehicles to bear the NATO and OTAN markings.

- 3 Boeing 707-320C Cargo Aircraft

- 17 Boeing E-3A AWACS

The aircraft operates from bases in:

- Vincenzo Florio Airport, Trapani, Italy (1986)

- Aviano Air Base

- San Vito dei Normanni Air Station

- Caserma Ederle

- Ørland, Norway (1983)

- Geilenkirchen, Germany (1982) (home base)

- Ramstein Air Base

- Laupheim Air Base

[edit] Research and Technology (R&T) at NATO

NATO currently possesses three Research and Technology (R&T) organisations:

- NATO Undersea Research Centre (NURC),[88] reporting directly to the Supreme Allied Command Transformation;

- Research and Technology Agency (RTA),[89] reporting to the NATO Research and Technology Organisation (RTO);

- NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A),[90] reporting to the NATO Consultation, Command and Control Organisation (NC3O).

- NATO ACCS Management Agency (NACMA), based in Brussels, manages around a hundred persons in charge of the Air Control and Command System (ACCS) due for 2009.

[edit] List of NATO operations

During the Cold War:

In Yugoslav Wars (1991–2001):

- Operation Sharp Guard (June 1993 – October 1996)

- Operation Deliberate Force (August - September 1995)

- Operation Joint Endeavour (December 1995 - 1996)

- Operation Allied Force (March - June 1999)

- Operation Essential Harvest (August - September 2001)

Other:

- International Security Assistance Force (since August 2003); ISAF was put under NATO command in August 2003, due to the fact that the majority of the contributed troops were from NATO member states.

- Baltic Air Policing (since March 2004); Operation Peaceful Summit temporarily enhanced this patrolling during the 2006 Riga Summit.[91]

- NATO-Sponsored Training of the Iraqi Police Force (part of the Multinational Force in Iraq since 2005)

[edit] Further reading

- Asmus, Ronald D. Opening NATO's Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era Columbia U. Press, 2002. 372 pp.

- Bacevich, Andrew J. and Cohen, Eliot A. War over Kosovo: Politics and Strategy in a Global Age. Columbia U. Press, 2002. 223 pp.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower. Vols. 12 and 13: NATO and the Campaign of 1952 : Louis Galambos et al., ed. Johns Hopkins U. Press, 1989. 1707 pp. in 2 vol.

- Daclon, Corrado Maria Security through Science: Interview with Jean Fournet, Assistant Secretary General of NATO, Analisi Difesa, 2004. no. 42

- Ganser, Daniele Natos Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe, ISBN 0-7146-5607-0

- Gearson, John and Schake, Kori, ed. The Berlin Wall Crisis: Perspectives on Cold War Alliances Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. 209 pp.

- Gheciu, Alexandra. NATO in the 'New Europe' Stanford University Press, 2005. 345 pp.

- Hendrickson, Ryan C. Diplomacy and War at NATO: The Secretary General and Military Action After the Cold War Univ. of Missouri Press, 2006. 175 pp.

- Hunter, Robert. "The European Security and Defense Policy: NATO's Companion - Or Competitor?" RAND National Security Research Division, 2002. 206 pp.

- Jordan, Robert S. Norstad: Cold War NATO Supreme Commander - Airman, Strategist, Diplomat St. Martin's Press, 2000. 350 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. The Long Entanglement: NATO's First Fifty Years. Praeger, 1999. 262 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. NATO Divided, NATO United: The Evolution of an Alliance. Praeger, 2004. 165 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S., ed. American Historians and the Atlantic Alliance. Kent State U. Press, 1991. 192 pp.

- Lambeth, Benjamin S. NATO's Air War in Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, 2001. 250 pp.

- Létourneau, Paul. Le Canada et l'OTAN après 40 ans, 1949–1989 Quebec: Cen. Québécois de Relations Int., 1992. 217 pp.

- Maloney, Sean M. Securing Command of the Sea: NATO Naval Planning, 1948–1954. Naval Institute Press, 1995. 276 pp.

- John C. Milloy. North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, 1948–1957: Community or Alliance? (2006), focus on non-military issues

- Powaski, Ronald E. The Entangling Alliance: The United States and European Security, 1950–1993. Greenwood, 1994. 261 pp.

- Ruane, Kevin. The Rise and Fall of the European Defense Community: Anglo-American Relations and the Crisis of European Defense, 1950–55 Palgrave, 2000. 252 pp.

- Sandler, Todd and Hartley, Keith. The Political Economy of NATO: Past, Present, and into the 21st Century. Cambridge U. Press, 1999. 292 pp.

- Smith, Jean Edward, and Canby, Steven L.The Evolution of NATO with Four Plausible Threat Scenarios. Canada Department of Defense: Ottawa, 1987. 117 pp.

- Smith, Joseph, ed. The Origins of NATO Exeter, UK U. of Exeter Press, 1990. 173 pp.

- Telo, António José. Portugal e a NATO: O Reencontro da Tradiçoa Atlântica Lisbon: Cosmos, 1996. 374 pp.

- Zorgbibe, Charles. Histoire de l'OTAN Brussels: Complexe, 2002. 283 pp.

[edit] References

- ^ "English and French shall be the official languages for the entire North Atlantic Treaty Organisation.", Final Communiqué following the meeting of the North Atlantic Council on September 17, 1949. "(..)the English and French texts [of the Treaty] are equally authentic(...)"The North Atlantic Treaty, Article 14

- ^ Boulevard Leopold III-laan, B-1110 BRUSSELS, which is in Haren, part of the City of Brussels. NATO homepage. Retrieved on 2006-03-07.

- ^ Fast facts. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ BBC On This Day "West Germany accepted into Nato" bbc.co.uk

- ^ Vulliamy, Ed (5 December 1990). "Secret agents, freemasons, fascists... and a top-level campaign of political 'destabilisation'". The Guardian: 12.

- ^ Würsten, Felix (October 2 2005). "Conference "Nato Secret Armies and P26": The dark side of the West". ETH Life Magazine.

- ^ Richards, Charles (1 December 1990). "Gladio is still opening wounds". The Independent: 12.

- ^ Concerning Finland, Sweden, and NATO members Norway and Denmark, see William Colby (CIA director from 1973 to 1976) and Peter Forbath, Honourable Men: My Life in the CIA, London: Hutchinson & Co., 1978 extract concerning Gladio stay-behind operations in Scandinavia available herePDF[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f NATO's Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe, by Daniele Ganser, Franck Cass, London, 2005 ISBN 0-7146-5607-0. See also NATO’s secret armies linked to terrorism?, by Daniele Ganser, December 17, 2004 — URL accessed on January 18, 2007

- ^ The European, Nov 9th 1990, quoted by Ganser, p25

- ^ Misinformation about "Gladio/Stay Behind" Networks Resurfaces. United States Department of State.

- ^ Translated from Bologna massacre Association of Victims Italian website. Google.com. Retrieved on 2006-07-30.(Italian)

- ^ Floyd, Chris (February 18 2005). "Global Eye - Sword Play". The Moscow Times.

- ^ Hans Depraetere and Jenny Dierickx, "La Guerre froide en Belgique" ("Cold War in Belgium") (EPO-Dossier, Anvers, 1986) (French)

- ^ Selahattin Celik, Türkische Konterguerilla. Die Todesmaschinerie (Köln: Mesopotamien Verlag, 1999; see also Olüm Makinasi Türk Kontrgerillasi, 1995), quoting Cuneyit Arcayurek, Coups and the Secret Services, p.190

- ^ Pierre Abramovici and Gabriel Périès, La Grande Manipulation, éd. Hachette, 2006

- ^ Howells, Tim (2005 November 28). "How our governments use terrorism to control us". The On-Line Journal Special Reports.

- ^ Rowse, Arthur E. (2004 January 31). "Gladio: The Secret U.S. War to Subvert Italian Democracy". Independent Media Center.

- ^ (June 24 2000) "US 'supported anti-left terror in Italy'". The Guardian.

- ^ Willan, Philip (June 21 2001). "Obituary: Paolo Emilio Taviani". The Guardian.

- ^ Gorbachev's Lost Legacy by Stephen F. Cohen (link) The Nation, February 24, 2005

- ^ In regards to the definition of aggression reached by consensus and approved by the United Nations General Assembly on 14 December 1974 as Resolution 3314 (XXIX): "Aggression is the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Charter of the UN."

- ^ http://www.nato.int/docu/update/2001/1001/e1002a.htm

- ^ NATO Seeking to Weaken CIS by Expansion — Russian General (link) MosNews 01.12.2005

- ^ Ukraine moves closer to NATO membership By Taras Kuzio (Link) Jamestown Foundation

- ^ Global Realignment [1]

- ^ Condoleezza Rice wants Russia to acknowledge USA's interests on post-Soviet space (Link) Pravda 04.05.2006

- ^ Nazemroaya, Mahdi Darius (May 17, 2007). "The Globalization of Military Power: NATO Expansion". Centre for Research on Globalization.

- ^ http://www.lemonde.fr0,1-0@2-3232,36-949296@51-947771,0.html

- ^ J. NYE, "NATO after Riga", 14 December 2006, http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/nye40

- ^ a b http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2007-04/19/content_6001014.htm

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6594379.stm

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6570533.stm

- ^ North Atlantic Treaty, Washington D.C. - 4 April 1949, [2], retrieved on February 22 2007.

- ^ http://www.nato.int/issues/map/index.html

- ^ http://www.mod.gov.al/botime/html/revista/2007/4/faqe13.htm

- ^ http://civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=13613

- ^ http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2007/04/13/feature-02

- ^ RADIO FREE EUROPE, Azerbaijan: Baku Seems Ambivalent About NATO Membership, March 22, 2007, [3]

- ^ ARMENIAN NEWS, Armenia-NATO Partnership Plan corresponds to interests of both parties, March 15, 2007, [4]

- ^ a b L. VESELICA, U.S. Backs Albania, Croatia, Macedonia NATO Bid, June 5, 2006

- ^ "Poll: Croatians against NATO membership" in The Malaysian Sun, May 4, 2006

- ^ N. RADIC, "Croatia mulls new strategy for NATO" in The Southeast European Times, 4 December 2006, [5]

- ^ http://www.seeurope.net/?q=node/6610

- ^ ?.

- ^ The Government is keeping the arrival of a NATO base to the border a secret. limun.hr (2007-05-17). Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- ^ "Clear majority of Finns still opposed to NATO membership", Helsingin Sanomat.

- ^ http://euobserver.com/9/23948

- ^ "Häkämies: Nato-jäsenyys Suomen etu", MTV3 Internet. Retrieved on 4-26-2007.

- ^ "Former President Ahtisaari: NATO membership would put an end to Finlandisation murmurs", Helsingin Sanomat.

- ^ "Finland, NATO, and Russia", Helsingin Sanomat.

- ^ a b Dragan Jočić, Minister of interior affairs of Serbia: Military independence is not isolation (in Serbian)

- ^ http://www.b92.net/eng/news/in_focus.php?id=96&start=0&nav_id=43417

- ^ "Sweden 'should join Nato plane pool'" in The Local, November 11, 2006, [6]

- ^ "Sweden could join new Nato force" in The Local, December 2, 2006, [7]

- ^ AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE, "Swedes Still Opposed to NATO Membership: Poll" in DefenseNews, May 15, 2006, [8]

- ^ http://en.for-ua.com/news/2006/03/20/114232.html

- ^ "Bulgaria’s capital to host NATO talks"

- ^ http://www.slovakspectator.sk/clanok.asp?cl=22855

- ^ http://www.interfax.kiev.ua/eng/go.cgi?31,20060424001

- ^ http://www.itar-tass.com/eng/level2.html?NewsID=4735634&PageNum=0

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/europe/09/14/ukraine.nato.reut/index.html?section=cnn_world

- ^ http://www.nato.int/issues/pfp/index.html http://www.nato.int/pfp/sig-date.html

- ^ http://www.nato.int/issues/eapc/index.html

- ^ http://www.nato.int/issues/ipap/index.html

- ^ http://www.nato.int/med-dial/home.htm

- ^ http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2006/p06-123e.htm

- ^ http://english.people.com.cn/200504/02/eng20050402_179138.html

- ^ http://www.nato.int/docu/speech/2006/s060427d.htm

- ^ "Israel, NATO to seek closer ties during Scheffer visit"

- ^ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Society_&_Culture/nato032705.html

- ^ Israel NATO Membership ‘Not on the Table’: Scheffer, REUTERS cable, September 2, 2006, mirrored on Defense News

- ^ Israel, NATO to seek closer ties during Scheffer visit, AFP cable, February 25, 2005, mirrored by The Daily Star

- ^ Aznar proposes NATO reform to Hoover Institute. The Spain Herald. Retrieved on 2006-03-22.

- ^ Aznar criticised the Iranian regime, called for a firm response from Europe. The Spain Herald. Retrieved on 2006-03-22.

- ^ National delegations to NATO What is their role?. NATO (2007-06-18). Retrieved on 2007-07-15.

- ^ Espen Barth, Eide; Frédéric Bozo (Spring 2005). Should NATO play a more political role?. Nato Review. NATO. Retrieved on 2007-07-15.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (2003-02-18). Reaching accord, EU warns Saddam of his 'last chance'. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved on 2007-07-15.

- ^ http://www.nato-pa.int/Default.asp?SHORTCUT=1

- ^ a b http://www.nato.int/cv/secgen.htm

- ^ Il nuovo fronte è a sud-est, Manlio Dinucci, Il Manifesto, June 26, 2004 (Italian)

- ^ Perché è un problema politico l'ampliamento della base Usa, Manlio Dinucci, Il Manifesto, January 18, 2007 (Italian)

- ^ Italians march in US base protest, BBC, 17 February 2007 (English)

- ^ Alliance Ground Surveillance, NATO (last updated on October 27, 2006 — URL accessed on January 18, 2007

- ^ El gobierno español pretende que la OTAN instale en Zaragoza el centro de mando del sistema de vigilancia y espionaje global de los Estados Unidos, June 28, 2006 on www.antimilitaristas.org, (Spanish)

- ^ a b OTAN - Le grand jeu des bases militaires en terre européenne, Manlio Dilucci, French translation published on May 9, 2006 in Le Grand Soir newspaper of an article originally published in Il Manifesto on April 30, 2006

- ^ Djibouti: a new army behind the wire, Le Monde diplomatique, February 2003 (English) (+ (French)/(Portuguese))

- ^ http://www.nurc.nato.int

- ^ http://www.rta.nato.int

- ^ http://www.nc3a.nato.int

- ^ L. NEIDINGER "NATO team ensures safe sky during Riga Summit" in Air Force Link, December 8, 2006, [9]

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

- NATO

- NATO Code of Best Practice for C2 AssessmentPDF (1.68 MiB)

- History of NATO – the Atlantic Alliance - UK Government site

- Basic NATO Documents

- The Globalization of Military Power: NATO Expansion (CRG)

- 'NATO force 'feeds Kosovo sex trade' (The Guardian)

- NATO Maintenance and Supply Agency (NAMSA) Official Website

- NATO Consultation, Command and Control Agency (NC3A) Official Website

- Joint Warfare Centre

- NATO Response Force Article

- NATO searches for defining role

- Official Article on NATO Response Force

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding NATO

- Balkan Anti NATO Center, Greece

- NATO Defense College

- Atlantic Council of the United States

- CBC Digital Archives - One for all: The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

- NATO at Fifty: New Challenges, Future Uncertainties U.S. Institute of Peace Report, March 1999

- NATO at 50

- Ukraine shelves bid to join NATO

- Operation Deny Flight fact sheet

- National Model NATO

- The Impact of NATO forces in Afghanistan An analysis of the effects of the U.S. led occupation on the political and social climate of Afghanistan.

- ESDI evolution in NATO: The presentation of the Eurocorps-Foreign Legion concept and its Single European Regiment at the European Parliament in June 2003

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Members | Belgium · Bulgaria · Canada · Czech Republic · Denmark · Estonia · France · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Italy · Latvia · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Netherlands · Norway · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Slovakia · Slovenia · Spain · Turkey · United Kingdom · United States |  |

| Candidates | Albania · Croatia · Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) · * | |

Categories: All articles with dead external links | Articles with dead external links since April 2007 | All articles with unsourced statements | Articles with unsourced statements since May 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since March 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since September 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since October 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since February 2007 | Acronyms | Anti-communism | Cold War treaties | International military organizations | Multiregional international organizations | Military acronyms | Military alliances | NATO | Foreign relations of the Soviet Union | 1949 establishments | Organisations based in Belgium | Supraorganizations | American influence in post-WWII Europe