Billy the Kid

| Billy the Kid | |

|---|---|

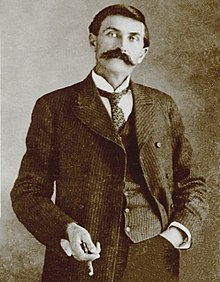

Billy the Kid c. 1880, enhanced version of the iconic photo of the outlaw

|

|

| Born | Henry McCarty September 17 or November 23, 1859 (disputed) Manhattan, New York City |

| Died | July 14, 1881 (aged 21) Fort Sumner, New Mexico |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Old Fort Sumner Cemetery 34°24′13″N 104°11′37″W / 34.40361°N 104.19361°W |

| Other names | William H. Bonney, Henry Antrim, Kid Antrim |

| Occupation |

|

| Height | 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) at age 17[1] |

| Weight | 135 lb (61 kg) at age 17[1] |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Joseph McCarty (brother) |

Billy the Kid (born Henry McCarty, and also known as William H. Bonney; 1859 – July 14, 1881) was an American Old West gunfighter who participated in the New Mexico Territory's Lincoln County War of 1878. He is known to have killed eight men.[2][3]

His first arrest was for stealing food in late 1875, and within five months he was arrested for stealing clothing and firearms. His escape from jail two days later and flight from New Mexico Territory into the neighboring Arizona Territory made him both an outlaw and a federal fugitive. After murdering a blacksmith during an altercation in August 1877, Bonney became a wanted man in Arizona Territory and returned to New Mexico, where he joined a group of cattle rustlers. He became a well-known figure in the region when he joined the Regulators and took part in the Lincoln County War. In April 1878, however, the Regulators killed three men, including Lincoln County Sheriff William J. Brady and one of his deputies. Bonney and two other Regulators were later charged with killing all three men.

Bonney's notoriety grew in December 1880 when the Las Vegas Gazette in Las Vegas, New Mexico, and the New York Sun carried stories about his crimes.[4] He was captured by Sheriff Pat Garrett later that same month, tried and convicted of the murder of Brady in April 1881, and sentenced to hang in May of that year. Bonney escaped from jail on April 28, 1881, killing two sheriff's deputies in the process, and evaded capture for more than two months. He ultimately was shot and killed by Garrett in Fort Sumner on July 14, 1881, aged 21. Over the next several decades, legends grew that Bonney had not died that night, and a number of men claimed they were him.[5]

Contents

Early life[edit]

Henry McCarty was born in Manhattan, New York City on September 17, 1859, to Catherine (née Devine) McCarty, and was baptized on September 28, 1859, in the Church of St. Peter.[a] There has been confusion among historians about McCarty's birthplace and birth date, and they remain unsettled.[7][8][9] His younger brother, Joseph McCarty was born in 1863.[10]

Following the death of her husband Patrick, Catherine McCarty and her sons moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, where she met William Henry Harrison Antrim. The McCarty family moved with Antrim to Wichita, Kansas in 1870.[11] After moving again a few years later, Catherine married Antrim on March 1, 1873, at the First Presbyterian Church in Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory; both McCarty and his brother Joseph were witnesses to the ceremony.[12][13] Shortly afterward, the family moved from Santa Fe to Silver City, New Mexico. Joseph McCarty took his stepfather's surname, and began using the name "Joseph Antrim."[10] Catherine McCarty died of tuberculosis on September 16, 1874.[14]

First crimes[edit]

McCarty was 14 years old when his mother died. Sarah Brown, the owner of a boardinghouse, gave him room and board in exchange for work. On September 16, 1875, McCarty was caught stealing food.[15][16] Ten days later, McCarty and George Schaefer robbed a Chinese laundry, stealing clothing and two pistols. McCarty was charged with theft, and was jailed. He escaped two days later, and became a fugitive,[15] as noted in the Silver City Herald the next day, the first story published about him. McCarty located his stepfather, and stayed with him for a while until Antrim threw him out, but not before McCarty stole clothing and guns from him. It was the last time the two saw each other.[17]

After leaving Antrim, McCarty traveled to southeastern Arizona Territory, where he worked as a ranch hand, gambling his wages in nearby gaming houses.[18] In 1876, he was hired as a ranch hand by well-known rancher Henry Hooker.[19][20] During this time, he became acquainted with John R. Mackie, a Scottish-born criminal and former U.S. Cavalry private who, following his discharge, remained in the vicinity of Camp Grant, a nearby United States Army post. The two men soon began stealing horses from local soldiers.[21][22] McCarty became known as "Kid Antrim" because of his youth, slight build, clean-shaven appearance, and his personality.[23][24]

On August 17, 1877, McCarty was at a saloon in the village of Bonita when he got into an argument with Francis "Windy" Cahill, a blacksmith. Cahill, who reportedly had bullied McCarty, and called him names on more than one occasion, called McCarty a pimp. McCarty in turn called Cahill a "son of a bitch," whereupon Cahill threw McCarty to the floor, and the two struggled for McCarty's revolver. McCarty shot and mortally wounded Cahill. A witness said, "[Billy] had no choice; he had to use his equalizer." Cahill died the following day.[25][26] McCarty fled but returned to town a few days later, and was apprehended by Miles Wood, the local Justice of the Peace. McCarty was detained and held in the Camp Grant guardhouse, but escaped before law enforcement could arrive.[27]

McCarty stole a horse, and fled Arizona Territory for New Mexico Territory,[28] but Apaches took the horse from him, leaving him to walk many miles to the nearest settlement. At Fort Stanton in the Pecos Valley,[29] starving and near death, he went to the home of friend and Seven Rivers Warriors gang member John Jones, whose mother Barbara nursed McCarty back to health.[30][31] After regaining his health, McCarty went to Apache Tejo, a former army post, where he joined a band of rustlers who raided herds owned by cattle magnate John Chisum in Lincoln County. After McCarty was spotted in Silver City by a resident, his involvement with the gang was mentioned in a local newspaper.[32]

At some point in 1877, McCarty began to refer to himself as "William H. Bonney".[31]

Lincoln County War[edit]

Prelude[edit]

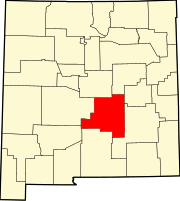

After returning to New Mexico, Bonney worked for English businessman and rancher John Henry Tunstall (1853-1878), as a cowboy in Lincoln County, near Rio Felix, a tributary of the Rio Grande. Tunstall, along with his business partner and lawyer Alexander McSween, was an opponent of an alliance formed by three Irish-American businessmen: Lawrence Murphy, James Dolan, and John Riley. The three men had wielded an economic and political hold over Lincoln County since the early 1870s, due in part to their ownership of a beef contract with nearby Fort Stanton and a well-patronized dry goods store in Lincoln.

In February 1878, McSween still had an outstanding debt of $8,000 owed to Dolan, who obtained a court order and asked Lincoln County Sheriff William J. Brady to attach nearly $40,000 worth of Tunstall's property and livestock. Tunstall put Bonney in charge of nine prime horses, and told him to relocate them to his ranch for safekeeping. Meanwhile, Sheriff Brady assembled a large posse to seize Tunstall's cattle.[33][34]

On February 18, 1878, Tunstall learned of the posse's presence on his land, and rode out to intervene. During the encounter, one member of the posse shot Tunstall in the chest, knocking him off his horse. Another posse member took Tunstall's gun, and killed him with a shot to the back of his head.[34][35] Tunstall's murder ignited the conflict between the two factions that became known as the Lincoln County War.[34][36]

Build-up[edit]

After Tunstall was killed, Bonney and Dick Brewer swore affidavits against Brady and those in his posse, and obtained murder warrants from Lincoln County justice of the peace John B. Wilson.[37] On February 20, 1878, while attempting to arrest Brady, the sheriff and his deputies happened on and arrested Bonney and two other men riding with him.[38] Deputy U.S. Marshal Rob Widenmann, a friend of Bonney, along with a detachment of soldiers, captured Sheriff Brady's jail guards, put them behind bars, and released Bonney and Brewer.[39]

Bonney then joined the Lincoln County Regulators, and on March 9 they captured Frank Baker and William Morton, both accused of killing Tunstall. The men were killed while allegedly trying to escape.[40] On April 1, the Regulators ambushed Sheriff Brady and his deputies, and during the battle Bonney was wounded in the thigh.[41]

Three days later, on the morning of April 4, 1878, during a shootout at Blazer's Mill between the Regulators and buffalo hunter Buckshot Roberts, Bonney's friend Dick Brewer was killed[42] along with Roberts, Sheriff Brady, and Deputy Sheriff George W. Hindman. Warrants were issued for several participants on both sides, and Bonney and two others were charged with killing the three men.[43]

Battle of Lincoln (1878)[edit]

On the night of Sunday, July 14, McSween and the Regulators, by now a group of fifty or sixty men, went to Lincoln and stationed themselves in the town among several buildings.[44] At the McSween residence were Bonney, Florencio Chavez, Jose Chavez y Chavez, Jim French, Harvey Morris, Tom O'Folliard, and Yginio Salazar, among others. Another group led by Marin Chavez and Doc Scurlock positioned themselves on the roof of a saloon. Henry Newton Brown, Dick Smith and George Coe defended a nearby adobe bunkhouse.[45][46]

On Tuesday, July 16, the newly appointed sheriff, George Peppin, sent sharpshooters to kill the McSween defenders at the saloon. Peppin's men retreated when one of the snipers, Charles Crawford, was killed by Fernando Herrera. Peppin then sent a request for assistance to Colonel Nathan Dudley, USA, commandant of nearby Fort Stanton. Dudley wrote a reply to Peppin turning him down, but then later arrived in Lincoln with troops, turning the tide of the battle in favor of the Murphy-Dolan faction.[47][48]

On Friday, July 19, a shooting war broke out. All of McSween's supporters gathered inside the McSween house. When Deputy Sheriff Jack Long and Buck Powell set fire to the building, the occupants began to shoot their weapons. After all but one room of the home had been engulfed by flames, Bonney and the others fled the building. During the confusion, Alexander McSween was shot and killed by Robert W. Beckwith, who was then shot and killed by Bonney.[49][50]

Outlaw[edit]

Bonney and three other survivors of the so-called Battle of Lincoln were near the Mescalero Indian Agency when the agency bookkeeper, Morris Bernstein, was murdered on August 5, 1878. All four were indicted for the murder, despite conflicting evidence that Bernstein had actually been killed by Constable Atanacio Martinez. All of these indictments were later quashed, except for Bonney's.[51][52]

On October 5, 1878, U.S. Marshal John Sherman informed newly appointed and inaugurated Territorial Governor and former Army general Lew Wallace that he held warrants for several men including "William H. Antrim, alias Kid, alias Bonny [sic]" but was unable to execute them "owing to the disturbed condition of affairs in that county, resulting from the acts of a desperate class of men."[53] Wallace issued an amnesty proclamation on November 13, 1878, which pardoned anyone involved in the Lincoln County War since the Tunstall murder of February 18, 1878. It specifically did not apply to any person who had been convicted of or was under indictment for a crime, and therefore excluded Bonney.[54][55]

On February 18, 1879, Bonney and friend Tom O'Folliard were in Lincoln when attorney Huston Chapman was shot and his corpse set on fire while Bonney and O'Folliard watched. According to eyewitnesses, the pair were innocent bystanders forced at gunpoint by Jesse Evans to witness the murder.[56][57]

Bonney later wrote to Governor Lew Wallace with an offer to provide information on the Chapman murder in exchange for amnesty. Bonney met with Wallace in Lincoln on March 15, 1879, discussing the case for over an hour. Wallace promised Bonney a complete pardon if he would offer his testimony to a grand jury regarding what he knew about the Chapman murder. On March 20, Wallace wrote to Bonney, "to remove all suspicion of understanding, I think it better to put the arresting party in charge of Sheriff Kimbrell [sic] who shall be instructed to see that no violence is used."[58] On March 21, Bonney let himself be "captured" by a posse led by Sheriff George Kimball of Lincoln County. As agreed, Bonney provided a statement about Chapman's murder. Still jailed, weeks passed and Bonney began to suspect he had been used by Wallace and would never be granted the promised amnesty. Bonney escaped the Lincoln County Jail on June 17, 1879.[59]

Bonney avoided further violence until January 10, 1880, when he shot and killed Joe Grant, a newcomer to the area, at Hargrove's Saloon in Fort Sumner, New Mexico.[60] The Santa Fe Weekly New Mexican reported, "Billy Bonney, more extensively known as 'the Kid,' shot and killed Joe Grant. The origin of the difficulty was not learned."[61] According to other contemporary sources, Bonney had been warned that Grant intended to kill him. He walked up to Grant, told him he admired his revolver, and asked to examine it. Grant handed it over. Before returning the pistol, which Bonney noticed contained only three cartridges, he positioned the cylinder so the next hammer fall would land on an empty chamber. Grant suddenly pointed his pistol at Bonney's face and pulled the trigger. When Grant's pistol failed to fire, Bonney drew his own weapon, and shot Grant in the head. A reporter for the Las Vegas Optic quoted Bonney as saying the encounter "was a game of two and I got there first."[62][63]

In 1880 Bonney formed a friendship in with a rancher named Jim Greathouse, who later introduced him to Dave Rudabaugh. On November 29, 1880, Bonney, Rudabaugh and Billy Wilson ran from a posse led by sheriff's deputy James Carlyle. Cornered at Greathouse's ranch, Bonney told the posse they were holding Greathouse as a hostage. Carlyle offered to exchange places with Greathouse, and Bonney accepted the offer. However, Carlyle later attempted to escape by jumping through a window, but he was shot three times and killed. The shoot out ended in a standoff, as the posse withdrew and Bonney, Rudabaugh, and Wilson rode away.[64][65]

A few weeks after the Greathouse incident, Bonney, Rudabaugh, Wilson, Charlie Bowdre, Tom Pickett, and O'Folliard rode into Fort Sumner. Unknown to Bonney and his companions, a posse led by Pat Garrett was waiting for them at the fort. The posse opened fire, killing O'Folliard. The rest of the outlaws escaped unharmed.[66][67]

Capture and escape[edit]

With a $500 bounty posted by Governor Wallace on December 13, 1880,[68] Garrett continued his search for Bonney. On December 23, following the siege in which Bowdre was killed, Garrett and his posse captured Bonney along with Pickett, Rudabaugh and Wilson at Stinking Springs. The group of shackled prisoners, including Bonney, was taken to Fort Sumner, from which they were transported to Las Vegas, New Mexico. When they arrived on December 26, they were met by crowds of curious onlookers. The following day, an armed mob gathered at the train depot before the prisoners, who were already on board the train with Pat Garrett, departed for Santa Fe.[69] Deputy Sheriff Romero, backed by the angry group of men, demanded custody of Dave Rudabaugh, who had killed a local jailer. Garrett refused to surrender the prisoner, and there was a tense confrontation until he agreed to let the sheriff and two other men accompany the party to Santa Fe, where they would petition the governor to release Rudabaugh to them.[70] In a later interview with a reporter, Bonney indicated he was unafraid during the incident by claiming, "if I only had my Winchester I'd lick the whole crowd."[71][72] The Las Vegas (New Mexico) Gazette ran a story from a jailhouse interview conducted by one of the newspaper's reporters following Bonney's capture. During the interview, when the reporter stated he thought the prisoner appeared relaxed, Bonney replied, "What's the use of looking on the gloomy side of everything? The laugh's on me this time."[73] During his short career as an outlaw, Bonney would be the subject of numerous newspaper articles in the United States, some as far away as New York.[74]

After arriving in Santa Fe, Bonney sent four separate letters over the next three months to Governor Wallace seeking clemency. After Wallace refused to intervene,[75] Bonney went to trial in April 1881 in Mesilla, New Mexico.[76] Following two days of testimony, Bonney was found guilty of Sheriff Brady's murder; it was the only conviction secured against any of the combatants in the Lincoln County War. On April 13, he was sentenced by Judge Warren Bristol to hang, with his execution scheduled for May 13, 1881.[76] Legend says that upon sentencing, the judge told Bonney he was going to hang until he was "dead, dead, dead," and that Bonney's response was, "you can go to hell, hell, hell."[77] The historical record, however, states he did not speak after the reading of his sentence.[78]

Following his sentencing, Bonney was moved to Lincoln, where he was held under guard on the top floor of the town courthouse. On the evening of April 28, 1881, while Garrett was in White Oaks collecting taxes, Deputy Bob Olinger took five other prisoners across the street for a meal. This left the other deputy, James Bell, alone at the jail with Bonney, who requested to be taken outside to use the outhouse behind the courthouse. On the way back to the jail, Bonney, who was walking ahead of Bell up the stairs to his cell, hid around a blind corner, slipped out of his handcuffs, and surprised Bell, beating him with the loose end of the cuffs. During the ensuing scuffle, Bonney was able to grab Bell's revolver, and fatally shot him in the back as the deputy made for the stairs to get away.[79]

While Bonney's legs were still shackled, he was able to get into Garrett's office, where he took a loaded shotgun left behind by Olinger. Waiting at the upstairs window for Olinger to respond to the gunshot that killed Bell, Bonney called out to the deputy, "Look up, old boy, and see what you get." When Olinger looked up, Bonney shot and killed him.[79][80] After about an hour, Bonney was able to free himself from the leg irons with an axe.[81] He obtained a horse and rode out of town. Some stories say that he was singing as he left Lincoln.[80]

Death[edit]

While Bonney was on the run, Governor Wallace placed a new $500 bounty on the fugitive's head.[82][83][84] Almost three months after his escape, Garrett acted in response to rumors that Bonney was in the vicinity of Fort Sumner. Garrett and two deputies left Lincoln on July 14, 1881, to question one of the town's residents, a friend of Bonney's named Pete Maxwell.[85] Maxwell, son of land baron Lucien Maxwell, spoke with Garrett the same day for several hours. Around midnight, the pair sat in Maxwell's darkened bedroom when Bonney unexpectedly entered the room.[86]

Accounts vary as to the course of events. The canonical version states that as Bonney entered the room, he failed to recognize Garrett due to the poor lighting. Drawing his revolver and backing away, Bonney asked "¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?", Spanish for "Who is it? Who is it?". Recognizing Bonney's voice, Garrett drew his revolver, firing twice. The first bullet struck Bonney in the chest just above his heart, killing him.[86]

A few hours after the shooting, a local justice of the peace assembled a coroner's jury of six people. Maxwell and Garrett were interviewed by the jury members and Bonney's body was examined along with the place of the shooting. After the jury certified the body as Bonney's, the jury foreman was put on record by a local newspaper as stating, "It was 'the Kid's' body that we examined."[87] Bonney was given a wake by candlelight. He was buried the next day and his grave was denoted with a wooden marker.[88][89]

Five days after Bonney’s killing, Garrett traveled to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to collect the $500 reward offered by Governor Lew Wallace for his capture, dead or alive. William G. Ritch, the acting New Mexico governor, refused to pay the reward.[90] Over the next several weeks, the citizens of Las Vegas, Mesilla, Santa Fe, White Oaks, and other New Mexico cities raised over $7,000 bounty reward money for Garrett. A year and four days after Bonney's death, the New Mexico territorial legislature passed a special act to grant Garrett the $500 bounty reward promised by Governor Wallace.[91]

Because people had begun to claim that Garrett unfairly ambushed Bonney, Garrett felt the need to tell his side of the story. In response, Garrett called upon his friend, journalist Marshall Upson, to ghostwrite a book for him.[92] The collaboration led to the book The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid,[b] which was first published in April 1882. Although only a few copies sold following its release, the book eventually became a reference for historians who later wrote about Bonney's life.[92]

Rumors of survival[edit]

Over time, legends formed and grew that claimed Bonney was not killed, and that Garrett staged the incident and death out of friendship so that the outlaw could evade the law.[94] During the next half century and more, a number of men would claim they were Billy the Kid. Most were easily proven not to be Bonney, but two have remained topics of discussion and debate.

In 1948, a Central Texas man known as Ollie P. Roberts, who went by the nickname "Brushy Bill", began claiming he was Billy the Kid and went before New Mexico Governor Thomas Mabry seeking a pardon. His claims were summarily dismissed by the governor, and Roberts died shortly afterwards.[95] Nevertheless, Hico, Texas, Roberts' town of residence, capitalized on his claim by opening a Billy the Kid museum.[96]

John Miller, an Arizona man, also claimed that he was Bonney. This was unsupported by his family until 1938, some time after his death. Miller's body was buried in the state-owned Arizona Pioneers' Home Cemetery in Prescott, Arizona, and in May 2005, his teeth and bones [97] were exhumed and examined,[98] without permission from the state.[99] DNA samples from the remains were sent to a laboratory in Dallas, Texas, and testing to compare Miller's DNA with blood samples obtained from floorboards in the old Lincoln County courthouse and a bench where Bonney's body allegedly was placed after he was shot.[100] According to a July 2015 article in the Washington Post, however, the lab results were "useless".[97]

In 2004, researchers sought to exhume the remains of Catherine Antrim, Bonney's mother, "so her DNA could be tested and compared with DNA to be taken from the body buried under the Kid's gravestone".[101] As of 2012, her body had not been exhumed.[100]

In 2007,[102] author and amateur historian Gale Cooper filed a lawsuit against the Lincoln County Sheriff's Office under the state Inspection of Public Records Act to produce records of the results of the 2006 DNA tests and other forensic evidence collected in the Billy the Kid investigations.[103] In April 2012, 133 pages of documents were provided, and "...although they offered no conclusive evidence to prove or disprove the generally accepted story of the Kid's death at Garrett's hand,"[102] they did "...reveal that the records sought not only exist[ed], but that they could have been easily produced long ago."[100] In 2014, Cooper was awarded $100,000 in punitive damages but the decision was later overturned by a three judge panel of the New Mexico Court of Appeals [104]. The lawsuit ultimately cost Lincoln County a combined amount of nearly $300,000 for the judgement and associated fees.[102]

In February 2015, historian Robert Stahl petitioned a district court in Fort Sumner, asking the state of New Mexico to issue a death certificate for Bonney.[87] Taking a step further in July 2015, Stahl filed suit in the New Mexico Supreme Court. The suit asked the court to order the state's Office of the Medical Investigator to officially certify Bonney's death under New Mexico state law.[105]

Legacy[edit]

Photographs[edit]

Dedrick ferrotype[edit]

One of the few remaining artifacts of Bonney's life is an iconic 2-by-3-inch (5.1 cm × 7.6 cm) ferrotype taken of Bonney by an unknown portrait photographer sometime in late 1879 or early 1880. The image shows Bonney wearing a vest over a sweater, a slouch cowboy hat on his head and a bandanna around his neck, while holding an 1873 Winchester rifle with the weapon's butt resting on the floor. For years, this photo of Bonney was the only one scholars and historians agreed was authentic.[83] The ferrotype survived due to a friend of Bonney, Dan Dedrick, keeping the image after the outlaw's death. Passed down through Dedrick's family, the image was copied several times and appeared in numerous publications during the 20th century. In June 2011, the original was bought at auction for $2.3 million by billionaire businessman William Koch,[106] making it the most expensive item ever sold through Brian Lebel's Annual Old West Show & Auction.[107]

The image, which had been copied and published in various ways over the years, showed Bonney with his holstered Colt revolver on his left side. This fueled the commonly-held belief that the gunman was left-handed. This belief, however, did not take into account that the method used to make the original ferrotype was to use metal plates that produced reverse images. As a result, the photo showed Bonney's pistol on his left side, leading historians to believe he shot with his left hand.[108] In 1954, western historians James D. Horan and Paul Sann wrote that Bonney was "right-handed and carried his pistol on his right hip".[109] The opinion was confirmed by Clyde Jeavons, a former curator of the National Film and Television Archive.[110] Several Billy the Kid historians have written that Bonney was ambidextrous.[111][112][113][114]

Playing croquet[edit]

A tintype purchased in 2010 for $2.00 by Randy Guijarro at a memorabilia shop in Fresno, California, appears to show Bonney and members of the Regulators playing croquet. The photo, known popularly as the "Croquet Tintype" was reviewed by Old West history and tin-type photo experts in order to authenticate or deny the image's authenticity.[115] Some, including collector Robert G. McCubbin and outlaw historian John Boessenecker, informed the owner as early as 2013 that it was not Bonney in the photo.[116] Whitny Braun, a professor and researcher was able to locate an advertisement for croquet sets sold at Chapman's General Store in Las Vegas, New Mexico dated to the month of June 1878. Kent Gibson, a forensic video and still image expert from Los Angeles, offered his services of facial recognition software, and stated that Bonney is one of the individuals in the image.[115]

In August 2015, Lincoln State Monument officials and the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs said that despite the new research done for the documentary, they were "unable to confirm authentication of the photograph in question as being a picture of Billy the Kid or other members of the Lincoln County War era", according to Monument manager Gary Cozzens. A photo curator at the Palace of the Governors photo archives, Daniel Kosharek, said that the photo was "problematic on a lot of fronts", including how small the figures are and the lack of resemblance in the background—in New Mexican eyes—to Lincoln County or the state in general.[115] This skepticism was echoed a few days prior to the October 18, 2015, premiere of Billy The Kid: New Evidence on the National Geographic Channel, when the editorial staff at True West Magazine published an article presenting opinions of the photo's authenticity held by various writers and researchers. These were summed up with the statement, "no one in our office thinks this photo is of the Kid [and the Regulators]".[116]

In early October 2015, Kagin's, Inc., a California-based numismatic authentication firm, determined that the image was authentic after a number of experts, including those associated with the National Geographic special, examined it for over a year.[117] Kagin's has insured the tintype for $5 million.[118]

Posthumous pardon request[edit]

In 2010, New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson turned down a request for posthumous pardon of Bonney for the murder of Sheriff William Brady. The pardon considered was to be a follow-through on a promise made by former Governor Lew Wallace in 1879. Richardson's decision, citing "historical ambiguity", was announced on December 31, 2010, his last day in office.[119][120]

Grave marker[edit]

In 1931, Charles W. Foor, at the time an unofficial tour guide at the Fort Sumner Cemetery, spearheaded a drive to raise funds for a permanent marker at the graves of Bonney, O'Folliard, and Bowdre. As a result of his efforts, a stone memorial marked with the names of the three men and their death dates beneath the word "Pals" was erected in the center of the burial area.[121]

In 1940, stone cutter James N. Warner of Salida, Colorado, created and donated a new marker to the cemetery specifically for Bonney's grave.[122] It was stolen on February 8, 1981, but recovered days later in Huntington Beach, California. New Mexico Governor Bruce King arranged for the county sheriff to fly to California to bring it back to Fort Sumner,[123] where it was re-installed in May 1981. Although both markers are behind iron fencing, a group of vandals entered the enclosure at night in June 2012 and tipped over the stone.[124]

Selected references in popular culture[edit]

Artwork[edit]

- Dick Brewer, Billy the Kid, and the Regulators; a painting by artist Andy Thomas[125]

Literature[edit]

- Billy The Kid (1958), a serial poem by Jack Spicer[126]

- Billy the Kid (1962), an episode title in the Lucky Luke comic book series by Goscinny and Morris[127]

- The Collected Works of Billy the Kid: Left-handed Poems, by Michael Ondaatje, 1970 biography in the form of experimental poetry[128]

- The Illegal Rebirth of Billy the Kid (1991) is a science fiction novel by Rebecca Ore[129]

- Anything for Billy (1988) is a fictionalized account of Billy's last year by Larry McMurtry[130]

- Lucky Billy: a novel about Billy the Kid (2008), is a novel by John Vernon, a professor at Binghamton University[131]

- The novels, Inferno and Escape from Hell, by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, feature interactions between the novels' contemporary main characters traversing Dante's Inferno and Billy the Kid[132]

- The Kid (2016), a novel of Billy the Kid's life by Ron Hansen[133]

Film[edit]

- Billy the Kid, a 1911 silent film directed by Laurence Trimble and starring Tefft Johnson[134]

- Billy the Kid, 1930 widescreen film directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown as Billy and Wallace Beery as Pat Garrett[135]

- Billy the Kid Returns, 1938: Roy Rogers plays a dual role, Billy the Kid and his dead-ringer lookalike who shows up after the Kid has been shot by Pat Garrett.[136]

- Billy the Kid, 1941 remake of the 1930 film, starring Robert Taylor and Brian Donlevy[137]

- Bob Steele and Buster Crabbe played Billy the Kid in a series of 42 western films from 1940 through 1946, released by Poverty Row studio Producers Distributing Corporation. Some of the titles include Blazing Frontier, The Renegade, Cattle Stampede, and Western Cyclone (1943).[138] In a 1952 film, Allan "Rocky" Lane goes after Billy the Kid's lost treasure.[139]

- The Outlaw, Howard Hughes' 1943 motion picture starring Jack Buetel as Billy and featuring Jane Russell in her breakthrough role as the Kid's fictional love interest[140][141]

- I Shot Billy the Kid, a 1950 film directed by William Berke and starring Don "Red" Barry as Billy[142]

- The Kid from Texas (1950) starring Audie Murphy as Billy the Kid[143]

- The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954, Columbia Pictures Corporation) starring Scott Brady as the Kid, James Griffith as Pat Garrett, Betta St. John as Nita Maxwell, and Alan Hale, Jr. as Bob Olinger[144][145]

- The Left Handed Gun, Arthur Penn's 1958 motion picture based on a Gore Vidal teleplay, starring Paul Newman as Billy and John Dehner as Garrett[146][147]

- The Boy from Oklahoma (1954), with Tyler MacDuff in the role of Billy the Kid[148]

- Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966), directed by William Beaudine, has Count Dracula, played by John Carradine, traveling to the Old West, where he takes a shine to Billy's fiancee and tries to turn her into a vampire. Chuck Courtney co-stars as Billy.[149][150]

- Chisum (1970), set during the Lincoln County War, was directed by Andrew V. McLaglen and stars Geoffrey Deuel as Billy and Glenn Corbett as Pat Garrett.[151]

- Dirty Little Billy (1972), set during Billy's early years as a criminal, starred Michael J. Pollard[152]

- Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Sam Peckinpah's 1973 motion picture with Kris Kristofferson as Billy, James Coburn as Pat Garrett, and with a soundtrack by Bob Dylan, who also appears in the movie[153]

- Young Guns, Christopher Cain's 1988 motion picture starring Emilio Estevez as Billy and Patrick Wayne as Pat Garrett[154]

- Gore Vidal's Billy the Kid, Gore Vidal's 1989 television film starring Val Kilmer as Billy and Duncan Regehr as Pat Garrett[155]

- Young Guns II, Geoff Murphy's 1990 motion picture starring Emilio Estevez as Billy and William Petersen as Pat Garrett[156]

- Purgatory, Uli Edel's 1999 made-for-TV movie starring Donnie Wahlberg as Deputy Glen/Billy The Kid[157]

- Requiem for Billy the Kid, Anne Feinsilber's 2006 motion picture starring Kris Kristofferson[158]

- Birth of a Legend, a 2011 film in two parts based on Frederick Nolan's book The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History directed by Andrew Wilkinson[159]

Music[edit]

- "Billy the Kid", a folksong in the public domain, was published in John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax's American Ballads and Folksongs album,[160] and also their Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads album.[161] Members of the Western Writers of America chose it as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time.[162]

- "Billy the Kid" folksong sung by Woody Guthrie, recorded by Alan Lomax in 1940 for the Library of Congress (#3412 B2), with a melody Guthrie later used for his song "So Long, it's Been Good to Know You". He also recorded it in 1944 for Moe Asch's Asch/Folkways label (MA67).[163]

- Bob Dylan's album Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, soundtrack of the 1973 film by Sam Peckinpah.[153]

- "The Ballad of Billy the Kid", song sung by Billy Joel on the 1973 Piano Man album.

- Charlie Daniels recorded the song "Billy the Kid" on his 1976 album High Lonesome.[164] Chris LeDoux also covered the song on his album Haywire.[165]

- Joe Ely recorded the song "Me and Billy the Kid" on his 1987 album Lord of the Highway.[166]

- Running Wild recorded the song "Billy the Kid" on their 1991 album Blazon Stone.[167]

- Tom Petty wrote the song "Billy the Kid", released on his 1999 album Echo.[168]

- Dia Frampton's "Billy the Kid," on the 2011 album Red.[169]

- Jon Bon Jovi's album, Blaze of Glory, was used as part of the soundtrack for Young Guns II.[170]

- Ry Cooder recorded the folk song "Billy the Kid", on the album Into The Purple Valley,[171] with his own melody and instrumental. It was also on Ry Cooder Classics Volume II.[172]

- Marty Robbins recorded the folk song "Billy the Kid" on his album Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs.[173]

Stage[edit]

- Billy the Kid, 1906 Broadway play co-written by Joseph Santley and Walwin (Walter) Woods.[174]

- Aaron Copland's Billy the Kid, music and ballet that premiered in 1938.[175]

- Michael McClure's 1965 play The Beard recounts a fictional meeting between Billy the Kid and Jean Harlow.[176]

- Michael Ondaatje's 1973 play, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid.[177]

Television and radio[edit]

- The first episode of the Gunsmoke radio series, broadcast on April 2, 1952 and titled "Billy the Kid", purports to tell of Billy's first murder as a runaway boy and credits Matt Dillon with giving him the "Billy the Kid" moniker.[178]

- The CBS radio series Crime Classics told the story of Billy the Kid in its October 21, 1953 episode (#17) titled "Billy Bonney – Bloodletter". The episode featured Sam Edwards as Billy the Kid and William Conrad as Pat Garrett.[179]

- Richard Jaeckel played The Kid in a 1954 episode of the syndicated television series Stories of the Century.[180]

- The NBC series The Tall Man ran from 1960 to 1962, starring Clu Gulager as Billy the Kid and Barry Sullivan as Pat Garrett.[181]

- Robert Vaughn starred as Billy the Kid in a 1957 episode ("Billy the Kid") of the series Tales of Wells Fargo.

- Robert Blake starred as Billy the Kid in the 1966 Death Valley Days episode "The Kid from Hell's Kitchen".[182]

- Robert Walker Jr. starred as Billy the Kid in a 1967 episode of the Irwin Allen science fiction series Time Tunnel.[183]

- American Experience, Billy the Kid, aired on PBS January 9, 2012.[184]

- Derek Chariton played Billy the Kid in four episodes of the 2016 miniseries The American West.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Letter from Rev. James B. Roberts, Church of St. Peter, New York City, to Jack DeMattos, March 24, 1979.[6]

- ^ The full title of the Garrett-Upson book was The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid, the Noted Desperado of the Southwest, Whose Deeds of Daring and Blood Made His Name a Terror in New Mexico, Arizona and Northern Mexico. By Pat. F. Garrett, Sheriff of Lincoln Co., N.M., By Whom He Was Finally Hunted Down and Captured by Killing Him.[93]

References[edit]

Citations

- ^ a b Utley 1989, p. 15.

- ^ Rasch 1995, pp. 23–35.

- ^ Wallis 2007, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 145–146.

- ^ "The Old Man Who Claimed to Be Billy the Kid". Atlas Obscura. 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ DeMattos 1980.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Rasch & Mullin 1953, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Rasch 1954, pp. 6–11.

- ^ a b Nolan 1998, pp. 15, 29.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Nolan 1998, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Nolan 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Nolan 2009, p. 8.

- ^ a b "Billy The Kid: Facts, information and articles about Billy The Kid, famous outlaw, and a prominent figure from the Wild West". HistoryNet.com. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ Grant County Herald (Silver City, New Mexico), September 26, 1875.

- ^ Wallis 2007, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. 103.

- ^ "Billy the Kid". State of New Mexico. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Wallis 2007, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 16.

- ^ Radbourne, Allan; Rasch, Philip J. (August 1985). "The Story of 'Windy' Cahill". Real West (204): 22–27.

- ^ "This Date in History – August 17, 1877 – Billy the Kid kills his first man". History Channel. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Wroth, William H. "Billy the Kid". New Mexico Office of the State Historian. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. 119.

- ^ Nolan 1998, p. 77.

- ^ Hays, Chad (March 19, 2013). "Ma'am Jones A stitch in time". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Wallis 2007, p. 144.

- ^ Wallis 2007, pp. 123–131.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 188–190.

- ^ a b c Boardman, Mark (September 25, 2010). "The Tunstalls Return – John Tunstall's kin traveled from England to fathom death in Lincoln.". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 46.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 23–55.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (April 1, 2004). "I Shot the Sheriff (and I Killed a Deputy, Too) – Billy Kid and the Regulators vs Sheriff Brady and His Deputies". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (September 11, 2015). "Tunstall Ambushed – Regulators vs Dolan's Henchmen". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 56–60.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 233–249, 549.

- ^ Rickards, Colin. The Gunfight at Blazer's Mill, 1974 – pp. 36–37.

- ^ Wroth, William H. Billy the Kid. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Jacobsen 1994, p. 173.

- ^ Nolan 1992, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Utley 1987, p. 87.

- ^ Nolan 1992, p. 513.

- ^ "New Mexico Office of the State Historian | people". newmexicohistory.org. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ Nolan 1992, pp. 322–331.

- ^ Utley 1987, pp. 96–111.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 104–105, 107, 110.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 339–340, 342, 445, 514.

- ^ Utley 1987, p. 120.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 315, 515.

- ^ Utley 1987, pp. 122–123, 126–128, 141, 150, 154, 156–158.

- ^ Utley 1987, pp. 132–136, 139, 141, 143–144.

- ^ Nolan 1992, pp. 375–376, 378, 516–517.

- ^ Governor Lew Wallace to W.H. Bonney, March 20, 1879.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 111–125.

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (May 2, 2007). "The Tale of the Empty Chamber Billy the Kid vs Joe Grant". True West Magazine. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ Santa Fe Weekly New Mexican, January 17, 1880.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 131–133, 145, 203, 249–250.

- ^ Nolan 2009, pp. 397, 518, 572.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 143–146, 179, 204.

- ^ Nolan 1992, pp. 398–401.

- ^ Metz 1974, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 155–157, 256–257.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 147.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. 240.

- ^ Rasch 2007, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Metz 1974, pp. 76–85.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 157–166.

- ^ Staff writers (November 29, 2012). "Book Review: Billy the Kid's Writings, Words & Wit, by Gale Cooper". HistoryNet. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Utley 1989, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Wallis 2007, pp. 240–241.

- ^ a b Wallis 2007, p. 242.

- ^ "1881 Billy the Kid is shot to death". History.com. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Nolan, Frederick (April 28, 2015). ""What if everything we know about Billy the Kid is wrong?" – Special Report". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Utley 1989, p. 181.

- ^ a b Wallis 2007, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Jacobsen 1994, pp. 232.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 188.

- ^ a b Boardman, Mark (May 24, 2011). "The Holy Grail for Sale – The Billy the Kid tintype is on the auction block, and it might just clear half a million". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Villagran, Lauren (December 1, 2013). "Is this Billy the Kid?". Albuquerque Journal – Las Cruces Bureau. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Wallis 2007, pp. 245–246.

- ^ a b Wallis 2007, p. 247.

- ^ a b Klein, Christopher (February 27, 2015). "Historian Seeks Death Certificate to End Billy the Kid Rumors". History.com. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Rose, Elizabeth R. (December 31, 2012), "Ft. Sumner New Mexico: Where Billy The Kid met his demise", Santa Fe Examiner

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze; Gardner, Mark Lee (August 12, 2014). "A Shot in the Dark: Billy the Kid vs Pat Garrett". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ "(no title)". Santa Fe Daily New Mexican. 21 July 1881. p. 4.

- ^ (New Mexico Territorial Legislature 18 July 1882).

- ^ a b Utley 1989, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Utley 1989, p. 199.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. xiv.

- ^ Field & Stream. July 1981. pp. 106–. ISSN 8755-8599.

- ^ Texas Department of Transportation, Texas State Travel Guide, 2008, pp. 200–201

- ^ a b Miller, Michael E. (July 21, 2015). "One man's quest to bury the Wild West mystery of Billy the Kid's death". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

A family Bible put his age in 1881 at just 2 years old: far too young for even a criminal nicknamed 'the Kid'.

- ^ Banks, Leo W. "A New Billy the Kid?". Tucson Weekly. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Associated Press (October 24, 2006) 2 won't face charges in Billy the Kid quest, Deseret News. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- ^ a b c Burns, James T. (April 28, 2012). "Billy the Kid and New Mexico Open Records Law". Albuquerque Business Law. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Miller, Patrick (March 18, 2004). "Shootout over Billy the Kid". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c Villagran, Lauren (May 20, 2014). "Award ends suit over Billy the Kid records". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Associated Press (August 28, 2008) Lawsuit seeks DNA evidence for 1881 death of Billy the Kid, Fox News Channel. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- ^ "Billy the Kid quest evolves into records fight". pressreader.com. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Constable, Anne (July 17, 2015). "Historian asks state's high court to help set record straight on Billy the Kid's death". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Tripp, Leslie (June 26, 2011). "Billy the Kid photograph fetches $2.3 million at auction". CNN. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ^ "Billy the Kid portrait fetches $2.3m at Denver auction". BBC News US & Canada. June 26, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Adetunji, Jo (June 26, 2011). "Billy the Kid photograph sold at auction in Colorado for $2.3m". The Guardian. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ^ Horan, James D. and Sann, Paul. Pictorial History of the Wild West, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1954 – p. 57.

- ^ Mayes, Ian (March 3, 2001). "I kid you not". The Guardian. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- ^ Gardner, Mark Lee: To Hell on a Fast Horse: The Untold Story of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett (2011), pp. 91, 277

- ^ Nolan 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Goode, Stephen (June 10, 2007). "The fact and fiction of America's outlaw". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

Billy loved to sing and had a good voice, those who knew him claimed ... He was ambidextrous and wrote well with both hands.

- ^ a b c Constable, Anne (August 24, 2015). "Billy the Kid: A fan of croquet?". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Billy the Kid Experts Weigh in on the Croquet Photo". True West Magazine. October 14, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Booker, Brakkton (October 15, 2015). "$2 Photo Found at Junk Store Has Billy The Kid in It, Could Be Worth $5M". NPR. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (October 19, 2015). "Man who discovered rare Billy the Kid photo: 'The hunt is a really grand thing'". The Guardian. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ "No pardon for Billy the Kid". CNN. December 31, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ "An Outlaw by Any Name: Billy the Kid". New York Times. July 14, 2016.

- ^ Simmons 2006, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Simmons 2006, pp. 164–165.

- ^ "Billy the Kid's Elusive Tombstone / Old Fort Sumner and Billy the Kid's Grave". Cemeteries-of-tx.com. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Lohr, David (June 30, 2012). "'Billy the Kid' tombstone in New Mexico vandalized". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ Thomas, Andy. "Dick Brewer, Billy the Kid, and the Regulators". Andy Thomas. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ "Billy the Kid Paperback – 1959 by Jack Spicer (Author)". Amazon.com. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Billy the Kid (Lucky Luke #20) by Morris, René Goscinny". GoodReads. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Van Wart, Alice. "The Evolution of Form in Machael Ondaatje's The Collected Works of Billy the Kid and Coming Through Slaughter". Western University. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "The Illegal Rebirth of Billy The Kid Mass Market Paperback – May 15, 1991 by Rebecca Ore (Author)". Amazon.com. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Anything for Billy by Larry McMurtry – Reviews, Discussions, Bookclubs, Lists". Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben. Book Review: Lucky Billy The New York Times. November 28, 2008. Web. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- ^ "Inferno Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle – A Review". SFSite. 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Hagy, Alyson (2016-11-18). "Billy the Kid: The Novel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- ^ "Billy the Kid". SilentEra.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Wallis 2007, p. xvi.

- ^ "Billy The Kid Returns". Amazon.com. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Billy the Kid (1941)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Rowan, Terry (2013). The American Western: A Complete Film Guide. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-300-41858-0.

- ^ Boggs, Johnny D. Billy the Kid on Film, 1911–2012. McFarland

- ^ "The Outlaw (1943) – Overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ "Howard Hughes: The Outlaw (1943)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "I Shot Billy the Kid (1950)". Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Kid from Texas – Movie No. 4". audiemurphy.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954) – Overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ "The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Left Handed Gun (1958) – Overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "The Left Handed Gun (1958)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Boy from Oklahoma (1954)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966) – Overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "Billy the Kid vs. Dracula". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Chisum (1970)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Dirty Little Billy – overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ a b "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Young Guns (1988) – overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Goodman, Walter (May 10, 1989). "Vidal Draws a Bead on Good-Bad Old Billy the Kid". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Young Guns II (1990) – overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Purgatory (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Requiem for Billy the Kid (2007) – overview". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Birth of a Legend: Billy the Kid & the Lincoln County War (2011)". Amazon.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ MacMillan, (1934), p. 137

- ^ MacMillan, (1938), pp. 140–141. From Jim Marby, recorded in 1911, Library of Congress E659098.

- ^ Western Writers of America (2010). "The Top 100 Western Songs". American Cowboy. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014.

- ^ "Liner notes: Woody Guthrie / Buffalo Skinners: The Asch Recordings Vol 4 / Number 3: Billy the Kid" (PDF). Smithsonian Folkways. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ "Billy The Kid (Album Version) The Charlie Daniels Band From the Album High Lonesome". Amazon.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Dillon, Charlotte. "Chris LeDoux – Haywire". AllMusic. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Joe Ely 'Me and Billy the Kid'". Amazon.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Little Big Horn – Running Wild; "Billy the Kid"". Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Billy The Kid". Metro Lyrics. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Billy The Kid Lyrics". Metro Lyrics. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Jon Bon Jovi – Blaze of Glory". AllMusic. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ 1972 Reprise K44142

- ^ Japan 1992 P-Vine PCD 2541

- ^ "Marty Robbins Billy the Kid (2:19)". Last FM. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Billy the Kid on stage". The Post-Standard (Syracuse, New York) April 12, 1907. April 12, 1907. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016.

- ^ Walter Terry, Ballet Guide, 1976, p. 57

- ^ "First NYC major revival of 'The Beard' by Michael McClure". New York Theatre Wise. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Weeks, Jerome (January 1998). "Outlaw By Ondaatje". American Theatre. 15 (1): 12.

- ^ Gunsmoke radio show "Billy the Kid", first broadcast May 26, 1952

- ^ "The Crime Classics Radio Program". The Digital Deli. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Hutton, Paul Andrew (April 1, 2007). "Dreamscape Desperado: Who remembers Billy the Kid? – "Cinematic Excess"". True West Magazine. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Tall Man – NBC (ended 1962)". TV.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Kid from Hell's Kitchen". TV.com. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Time Tunnel (TV show) – Season 1, Episode 22 Billy the Kid". TV Guide. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Video: Billy the Kid – Watch American Experience Online". PBS Video. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

Bibliography

- Adams, Ramon F. (1960). A Fitting Death for Billy the Kid. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 8937525.

- Burns, Walter (2014). The Saga of Billy the Kid: The Thrilling Life of America's Original Outlaw. Garden City, New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63220-112-6. OCLC 894170041. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Coe, George W. (1934). Frontier Fighter: The Autobiography of George W. Coe Who Fought and Rode with Billy the Kid, as Related to Nan Hillary Harrison. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 692143776.

- DeMattos, Jack (November 1978). "The Search for Billy the Kid's Roots". Real West. No. 160. Real West.

- DeMattos, Jack (January 1980). "The Search for Billy the Kid's Roots – Is Over!". Real West. No. 167. Real West.

- DeMattos, Jack (August 1983). "Gunfighters of the Real West: Henry McCarty, Alias 'Billy the Kid'". Real West. No. 192. Real West.

- Dworkin, Mark J. (2015). American Mythmaker: Walter Noble Burns and the Legends of Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp, and Joaquín Murrieta. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Dykes, Jefferson (1952). Billy the Kid: The Bibliography of a Legend. Alburquerque, New Mexico: The University of New Mexico Press.

- Earle, James H. (1988). The Capture of Billy the Kid. College Station, Texas: Creative Publishing Co. ISBN 0-932702-44-9. OCLC 18052460.

- Edwards, Harold L. (1995). Goodbye Billy the Kid. College Station, Texas: Creative Publishing Co. ISBN 1-57208-000-0. OCLC 33335740.

- Fable, Edmund, Jr. (1980) [1881]. The True Life of Billy the Kid, The Noted New Mexican Outlaw. College Station, Texas: Creative Publishing Co. ISBN 0-932702-11-2. OCLC 6487191.

- Fulton, Maurice Garland (1968). Robert N. Nullin, ed. History of the Lincoln County War. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. OCLC 437868.

- Gardner, Mark Lee (2010). To Hell on a Fast Horse: Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, and the Epic Chase to Justice in the Old West. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-136827-1. OCLC 419859633.

- Garrett, Pat F. (1882). The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid (1st ed.). Santa Fe, New Mexico: New Mexican Printing and Publishing Company. OCLC 748293298.

- Hough, Emerson (September 1901). "Billy the Kid: The True Story of a Western 'Bad Man'". Everybody's Magazine. New York: The Ridgeway Company. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- Hunt, Frazier (2009) [1956]. The Tragic Days of Billy the Kid. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-717-5. OCLC 316327276.

- Jacobsen, Joel (1994). Such Men as Billy the Kid: The Lincoln County War Reconsidered. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2576-3. OCLC 29429457.

- Keleher, William Aloysius (2007) [1957]. Violence in Lincoln County 1869–1881. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-622-2. OCLC 182573474.

- Klasner, Lily; Chisum, John Simpson; Ball, Eve (1972). My Girlhood Among Outlaws. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-0354-4. OCLC 166482848.

- Koop, Waldo E. (1964). "Billy the Kid: The Trail of a Kansas Legend". Kansas City Posse of Westerners. IX (3).

- Metz, Leon C. (1983) [1974]. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman (reprint, revised ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1838-3. OCLC 18722891.

- McCubbin, Robert G. (May 2007). "The Many Faces of Billy the Kid". True West. True West.

- Metz, Leon C. (August 1983). "My Search for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid". True West. True West.

- Nolan, Frederick W. (2009). The Life and Death of John Henry Tunstall. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-722-9. OCLC 440562959.

- Nolan, Frederick W. (2009) [1992]. The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History (revised ed.). Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-721-2. OCLC 319064671. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Nolan, Frederick W. (1992). The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Nolan, Frederick (June 2003). "The Hunting of Billy the Kid". Wild West. Wild West.

- Nolan, Frederick (1998). The West of Billy the Kid. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3082-2.

- Nolan, Frederick (July 2000). "The Private Life of Billy the Kid". True West. True West.

- Nolan, Frederick W. (2007). The Billy the Kid Reader. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8446-3.

- Otero, Miguel (2006) [1936]. The Real Billy the Kid, With New Light on the Lincoln County War. New York: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-1-61139-100-8.

- Poe, John William (2006) [1933]. The Death of Billy the Kid (reprint ed.). Santa Fe: Sunstone Press Company.

- Radbourne, Allan; Rasch, Phillip J. (August 1985). "The Story of 'Windy' Cahill". Real West. No. 204. Real West.

- Rasch, Philip J.; Mullin, Robert N. (1953). "New Light on the Legend of Billy the Kid". New Mexico Folklore Record 7.

- Rasch, Philip J. (1954). "Dim Trails: The Pursuit of the McCarty Family". New Mexico Folklore Record 8.

- Rasch, Philip J. (1955). "The Twenty-One Men He Put Bullets Through". New Mexico Folklore Record 9.

- Rasch, Philip J. (January 1969). "A Second Look at the Blazer's Mill Affair". Frontier Times.

- Rasch, Philip J. (November 1987). "The Trials of Billy the Kid". Real West. No. 216. Real West.

- Rasch, Philip J. (1995). Trailing Billy the Kid. Stillwater, Oklahoma: Western Publications. ISBN 978-0-935269-19-2.

- Rasch, Philip J. (1997). Gunsmoke in Lincoln County. Stillwater, Oklahoma: Western Publications. ISBN 978-0-935269-24-6.

- Rasch, Philip J. (1998). Warriors of Lincoln County. Stillwater, Oklahoma: Western Publications. ISBN 978-0-935269-26-0.

- Rickards, Colin W. (1974). "The Gunfight at Blazer's Mill". Southwestern Studies Monograph No. 40. El Paso, Texas: Western Press.

- Simmons, Mark (2006). Stalking Billy the Kid: Brief Sketches of a Short Life. Sunstone Press. ISBN 0-86534-525-2.

- Tuska, Jon (1983). Billy the Kid: A Handbook. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9406-9.

- Utley, Robert M. (1987). High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1201-3. OCLC 15629305. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Utley, Robert M. (1989). Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9558-2. OCLC 37868038. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Wallis, Michael (2007). Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-06068-3. OCLC 77270750.

External links[edit]

- Billy the Kid Territory – guide by New Mexico Tourism Department

- Turk, David S. "Billy the Kid and the U.S. Marshals Service." Wild West Magazine. February 2007 (issued December 2006)

- "William "Billy The Kid" Bonney". Find a Grave. January 1, 2001. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- About Billy the Kid – comprehensive website by amateur historian Marcelle Brothers

- Billy the Kid

- 19th-century American criminals

- 1859 births

- 1881 deaths

- Cowboys

- American escapees

- American folklore

- American outlaws

- American people convicted of murder

- American people convicted of murdering police officers

- American people of Irish descent

- Cowboy culture

- Criminals from New York City

- Deaths by firearm in New Mexico

- Gunslingers of the American Old West

- Lincoln County Wars

- Outlaws of the American Old West

- People from De Baca County, New Mexico

- People from Manhattan

- People of the American Old West

- People of the New Mexico Territory

- People shot dead by law enforcement officers in the United States