Skagway, Alaska

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Municipality of Skagway | ||

|---|---|---|

| Borough | ||

Aerial view of Skagway, Alaska.

|

||

|

||

| Nickname(s): "Gateway to the Klondike" | ||

Map of Alaska highlighting Skagway |

||

| Coordinates: 59°27′30″N 135°18′50″W / 59.45833°N 135.31389°WCoordinates: 59°27′30″N 135°18′50″W / 59.45833°N 135.31389°W | ||

| Country | ||

| State | Alaska | |

| Founded | 1897 | |

| Incorporated (city) | June 28, 1900 | |

| Incorporated (borough) | June 5, 2007 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Mark Schaefer[1] | |

| • State senator | Dennis Egan (D) | |

| • State rep. | Sam Kito III (D) | |

| Area | ||

| • Borough | 464 sq mi (1,200 km2) | |

| • Land | 452 sq mi (1,170 km2) | |

| • Water | 12 sq mi (30 km2) | |

| Elevation | 33 ft (10 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Borough | 920 | |

| • Estimate (2016)[2] | 1,088 | |

| • Density | 2.0/sq mi (0.77/km2) | |

| Time zone | AKST (UTC−9) | |

| • Summer (DST) | AKDT (UTC−8) | |

| Zip code | 99840 | |

| Area code(s) | 907 | |

| FIPS code | 02-70760 | |

| GNIS feature ID | U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Skagway U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Skagway Municipality |

|

| Website | www.skagway.org | |

The Municipality and Borough of Skagway (/ˈskeɪɡweɪ/) is a first-class borough in Alaska on the Alaska Panhandle. As of the 2010 census, the population was 920.[3] Estimates put the 2015 population at 1,057 people. The population doubles in the summer tourist season in order to deal with more than 900,000 visitors.[4] Incorporated as a Borough on June 25, 2007, it was previously a city (urban Skagway located at 59°27′30″N 135°18′50″W / 59.45833°N 135.31389°W) in the Skagway-Yakutat-Angoon Census Area (now the Hoonah–Angoon Census Area).[4]

The port of Skagway is a popular stop for cruise ships, and the tourist trade is a big part of the business of Skagway. The White Pass and Yukon Route narrow gauge railroad, part of the area's mining past, is now in operation purely for the tourist trade and runs throughout the summer months. Skagway is also part of the setting for Jack London's book The Call of the Wild, Will Hobbs's book Jason's Gold, and for Joe Haldeman's novel Guardian, moreover, John Wayne's film "North to Alaska" was filmed nearby.

Skagway is derived from shԍagéi, a Tlingit idiom which figuratively refers to rough seas in the Taiya Inlet, that are caused by strong north winds.[5] (See, “Etymology and the Mythical Stone Woman,” below.)

Contents

History[edit]

Etymology and the Mythical Stone Woman[edit]

Skagway was derived from shԍagéi, a Tlingit idiom which figuratively refers to rough seas in the Taiya Inlet, that are caused by strong north winds.[5] Literally, shԍagéi means beautiful woman.[6] The word is also a gerund (verbal noun), derived from the Tlingit verb theme -sha-ka-l-ԍéi, which means, in the case of a woman, to be beautiful.[7]

The reason for its figurative meaning is that Shԍagéi or Skagway is the nickname of Kanagoo, the mythical woman who transformed herself into stone at Skagway bay and who (according to legend) causes the strong, channeled winds which blow toward Haines, Alaska.[8] The rough seas caused by these winds are therefore referred to by the use of Kanagoo’s nickname, which is Shԍagéi or Skagway.[9]

Except for the fact that “Kanagoo … lives in [Skagway] bay,”[8] the identity of the Kanagoo stone formation is not recorded. However, it is likely to be Face Mountain, which is seen from Skagway bay. The Tlingit name for Face Mountain translates to Kanagoo’s Image.[10]

Prehistory to the 21st century[edit]

The area around present-day Skagway was inhabited by Tlingit people from prehistoric times. They fished and hunted in the waters and forests of the area and had become prosperous by trading with other groups of people on the coast and in the interior.[citation needed]

One prominent resident of early Skagway was William "Billy" Moore, a former steamboat captain. As a member of an 1887 boundary survey expedition, he had made the first recorded investigation of the pass over the Coast Mountains, which later became known as White Pass. He believed that gold lay in the Klondike because it had been found in similar mountain ranges in South America, Mexico, California, and British Columbia. In 1887, he and his son, J. Bernard "Ben" Moore, claimed a 160-acre (650,000 m2) homestead at the mouth of the Skagway River in Alaska. Moore settled in this area because he believed it provided the most direct route to the potential goldfields. They built a log cabin, a sawmill, and a wharf in anticipation of future gold prospectors passing through.[citation needed]

The boundary between Canada and the United States along the Alaska Panhandle was only vaguely defined then (see Alaska boundary dispute). There were overlapping land claims from the United States' purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 and British claims along the coast. Canada requested a survey after British Columbia united with it in 1871, but the idea was rejected by the United States as being too costly, given the area's remoteness, sparse settlement, and limited economic or strategic interest.[citation needed]

The Klondike gold rush changed everything. In 1896, gold was found in the Klondike region of Canada's Yukon Territory. On July 29, 1897, the steamer Queen docked at Moore's wharf with the first boat load of prospectors. More ships brought thousands of hopeful miners into the new town and prepared for the 500-mile journey to the gold fields in Canada. Moore was overrun by lot jumping prospectors and had his land stolen from him and sold to others.[11]

The population of the general area increased enormously and reached 30,000, composed largely of American prospectors.[citation needed] Some realized how difficult the trek ahead would be en route to the gold fields, and chose to stay behind to supply goods and services to miners. Within weeks, stores, saloons, and offices lined the muddy streets of Skagway. The population was estimated at 8,000 residents during the spring of 1898 with approximately 1,000 prospective miners passing through town each week. By June 1898, with a population between 8,000 and 10,000, Skagway was the largest city in Alaska.[12]

Due to the sudden influx of visitors to Skagway, some town residents began offering miners transportation services to aid them in their journeys to the Yukon, often at highly inflated rates. A group of miners upset with the treatment organized a town council to help protect their interests. But as the members of the council moved north to try their own hands at mining, control of the town reverted to the more unscrupulous, most notably Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith.[citation needed]

Between 1897 and 1898, Skagway was a lawless town, described by one member of the North-West Mounted Police as "little better than a hell on earth." Fights, prostitutes and liquor were ever-present on Skagway's streets, and con man "Soapy" Smith, who had risen to considerable power, did little to stop it. Smith was a sophisticated swindler who liked to think of himself as a kind and generous benefactor to the needy. He was gracious to some, giving money to widows and halting lynchings, while simultaneously operating a ring of thieves who swindled prospectors with cards, dice, and the shell game. His telegraph office charged five dollars to send a message anywhere in the world. Consequently, unknowing prospectors sent news to their families back home without realizing there was no telegraph service to or from Skagway until 1901.[13] Smith also controlled a comprehensive spy network, a private militia called the Skaguay Military Company, the town newspaper, the Deputy U.S. Marshal's office and an array of thieves and con-men who roamed about the town. Smith was shot and killed by Frank Reid and Jesse Murphy on July 8, 1898, in the famed Shootout on Juneau Wharf. Smith managed to return fire — some accounts claim the two men fired their weapons simultaneously — and Frank Reid died from his wounds twelve days later. Jesse Murphy is accredited as the man responsible for killing Smith.[14] Smith and Reid are now interred at the Klondike Gold Rush Cemetery, also known as "Skagway's Boot Hill."[15]

The prospectors' journey began for many when they climbed the mountains over the White Pass above Skagway and onward across the Canada–US border to Bennett Lake, or one of its neighboring lakes, where they built barges and floated down the Yukon River to the gold fields around Dawson City. Others disembarked at nearby Dyea, northwest of Skagway, and crossed northward on the Chilkoot Pass, an existing Tlingit trade route to reach the lakes. The Dyea route fell out of favor when larger ships began to arrive, as its harbor was too shallow for them except at high tide.[citation needed]

Officials in Canada began requiring that each prospector entering Canada on the north side of the White Pass bring with him one ton (909 kg) of supplies, to ensure that he did not starve during the winter. This placed a large burden on the prospectors and the pack animals climbing the steep pass.[citation needed]

In 1898, a 14-mile, steam-operated aerial tramway was constructed up the Skagway side of the White Pass, easing the burden of those prospectors who could afford the fee to use it. The Chilkoot Trail tramways also began to operate in the Chilkoot Pass above Dyea. In 1896, before the Klondike gold rush had begun, a group of investors saw an opportunity for a railroad over that route. It was not until May 1898 that the White Pass and Yukon Route began laying narrow gauge railroad tracks in Skagway. The railroad depot was constructed between September and December 1898. This destroyed the viability of Dyea, as Skagway had both the deep-water port and the railroad.[citation needed]

Construction of McCabe College, the first school in Alaska to offer a college preparatory high school curriculum, began in 1899. The school was completed in 1900.[citation needed]

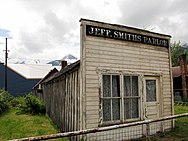

By 1899, the stream of gold-seekers had diminished and Skagway's economy began to collapse. By 1900, when the railroad was completed, the gold rush was nearly over. In 1900, Skagway was incorporated as the first city in the Alaska Territory. Much of the history of Skagway was saved by early residents, such as Martin Itjen, who ran a tour bus around the historical town. He was responsible for saving and maintaining the gold rush cemetery from complete loss. He purchased Soapy Smith's saloon (Jeff Smith's Parlor), from going the way of the wrecking ball, and placed many early artifacts of the city's early history inside and opened Skagway's first museum.[16]

In July 1923, President Warren G. Harding visited Skagway while on his historic tour through Alaska. Harding was the first President of the United States to travel and tour Alaska while in office.[17][18]

Skagway was one of the few towns in Alaska (along with Petersburg and Seward) to endorse the 1939 Slattery Report on Alaskan development through immigration, especially of Jews from Germany and Austria.[citation needed]

Geography[edit]

Skagway is located at 59°28′7″N 135°18′21″W / 59.46861°N 135.30583°W (59.468519, −135.305962).[19]

Skagway is located in a narrow glaciated valley at the head of the Taiya Inlet, the north end of the Lynn Canal, which is the most northern fjord on the Inside Passage on the south coast of Alaska. It is in the Alaska panhandle 90 miles northwest of Juneau, Alaska's capital city.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the borough has a total area of 464 square miles (1,200 km2), of which 452 square miles (1,170 km2) is land and 12 square miles (31 km2) (2.5%) is water.[19] It is currently the smallest borough in Alaska, having taken the title away from Bristol Bay Borough at its creation.

Adjacent boroughs[edit]

- Haines Borough, Alaska — south, west

- Stikine Region, British Columbia — north, east

National protected areas[edit]

- Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (part, also in Seattle, Washington)

- Tongass National Forest (part)

Climate[edit]

Skagway has a humid continental cool-summer climate (Köppen Dsb). It is in the rain shadow of the coastal mountains, though not as pronounced as the rain shadow in Southcentral Alaska, in the valley of the Susitna River, this still allows it to receive only half as much precipitation as Juneau and only a sixth as much as Yakutat. Although winters are too cold for the classification, precipitation patterns resemble a mediterranean climate due to the dry summers. The highest temperature recorded in Skagway is 92 °F or 33.3 °C in three separate years, most recently in 1975, and the lowest temperature recorded is −24 °F or −31.1 °C on February 2, 1947.

| Climate data for Skagway, Alaska | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 52 (11) |

60 (16) |

59 (15) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

77 (25) |

68 (20) |

59 (15) |

52 (11) |

92 (33) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 26.9 (−2.8) |

33.2 (0.7) |

39.4 (4.1) |

50.1 (10.1) |

58.7 (14.8) |

65.1 (18.4) |

66.9 (19.4) |

64.9 (18.3) |

57.4 (14.1) |

48.0 (8.9) |

36.3 (2.4) |

32.0 (0) |

48.2 (9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.0 (−5.6) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

33.2 (0.7) |

41.5 (5.3) |

49.4 (9.7) |

56.1 (13.4) |

58.7 (14.8) |

56.9 (13.8) |

50.9 (10.5) |

42.6 (5.9) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

41.5 (5.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17.3 (−8.2) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

32.8 (0.4) |

40.1 (4.5) |

47.1 (8.4) |

50.4 (10.2) |

48.9 (9.4) |

44.2 (6.8) |

37.2 (2.9) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

34.7 (1.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

−5 (−21) |

14 (−10) |

14 (−10) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

19 (−7) |

8 (−13) |

−6 (−21) |

−14 (−26) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.17 (55.1) |

1.84 (46.7) |

1.55 (39.4) |

1.20 (30.5) |

1.30 (33) |

1.11 (28.2) |

1.19 (30.2) |

2.19 (55.6) |

4.04 (102.6) |

4.24 (107.7) |

2.89 (73.4) |

2.43 (61.7) |

26.15 (664.1) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.2 (36.1) |

9.7 (24.6) |

3.3 (8.4) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.2 (3) |

8.6 (21.8) |

11.1 (28.2) |

49.2 (124.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 9 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 18 | 13 | 12 | 133 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Centre[20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 1,800 | — | |

| 1910 | 872 | −51.6% | |

| 1920 | 494 | −43.3% | |

| 1930 | 492 | −0.4% | |

| 1940 | 634 | 28.9% | |

| 1950 | 758 | 19.6% | |

| 1960 | 659 | −13.1% | |

| 1970 | 675 | 2.4% | |

| 1980 | 768 | 13.8% | |

| 1990 | 692 | −9.9% | |

| 2000 | 862 | 24.6% | |

| 2010 | 920 | 6.7% | |

| Est. 2016 | 1,088 | [2] | 18.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] 1790-1960[22] 1900-1990[23] 1990-2000[24] 2010-2016[3] |

|||

As of the census[25] of 2000, there were 862 people, 401 households, and 214 families residing in the city. The population density was 1.9 people per square mile (0.7/km2). There were 502 housing units at an average density of 1.1 per square mile (0.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.34% White, 3.02% Native American, 0.58% Asian, 0.23% Pacific Islander, 0.81% from other races, and 3.02% from two or more races. 2.09% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 401 households out of which 23.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.9% were married couples living together, 4.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.4% were non-families. 36.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.15 and the average family size was 2.81.

In the city the population was distributed with 20.5% under the age of 18, 5.2% from 18 to 24, 34.6% from 25 to 44, 31.2% from 45 to 64, and 8.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years old. For every 100 females there were 109.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 112.7 males.

Economy[edit]

Personal income[edit]

The median income for a household in the city was $49,375, and the median income for a family was $62,188. Males had a median income of $44,583 versus $30,956 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,700. About 1.0% of families and 3.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including none of those under age 18 and 4.5% of those age 65 or over.

Tourism[edit]

There are visitors to the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park and White Pass and Chilkoot Trails. Skagway has a historical district of about 100 buildings from the gold rush era. It receives about a million tourists annually,[citation needed] most of whom (about three quarters) come on cruise ships. The White Pass and Yukon Route operates its narrow-gauge train around Skagway during the summer months, primarily for tourists. The WPYR also ships copper ore from the interior.

Transportation[edit]

Skagway is one of three Southeast Alaskan communities that is connected to the road system; Skagway's connection is via the Klondike Highway, completed in 1978. This allows access to the lower 48, Whitehorse, the Yukon, northern British Columbia, and the Alaska Highway. This also makes Skagway an important port-of-call for the Alaska Marine Highway — Alaska's ferry system — and serves as the northern terminus of the important and heavily used Lynn Canal corridor. (The other Southeast Alaskan communities with road access are Haines and Hyder.)

The White Pass and Yukon Route is a railway that formerly linked Whitehorse, Yukon in Canada to Skagway, the railway's southernmost terminus. Today, trains travel several times a week from May through September from Skagway to the small community of Carcross, approximately 45 miles south/southwest of Whitehorse. There, passengers (mostly tourists) can make connections via bus to Whitehorse.

The Skagway Airport receives service from two bush carriers: Wings of Alaska, and Air Excursions.

Media[edit]

Local radio and newspapers[edit]

Skagway is served by its local semimonthly newspaper, The Skagway News, as well as regional public radio station KHNS, which has its principal studios in nearby Haines but also has studios and programs based in Skagway. Juneau radio station KINY operates a translator in Skagway which serves the entire town.

Skagway also receives copies of the free regional newspaper Capital City Weekly.

Featured in media[edit]

In the Three Stooges short In the Sweet Pie and Pie, Skagway receives a humorous mention: "Edam Neckties, with three convenient locations: Skagway, Alaska; Little America; and Pago Pago."

Skagway is featured in the 1955 Western The Far Country, directed by Anthony Mann.

Skagway is a town featured in the computer game The Yukon Trail.

In an episode of Homeland Security USA, the border crossing in Skagway was featured as being the least-used crossing in the United States.

Chief Inspector Fenwick often dryly referred to nearby "big city" "Skagway" when sending his mounty, Dudley Do-Right, to capture the show's evil nemesis, Snidely Whiplash.

Health care[edit]

Skagway is served by Dahl Memorial Clinic, the only primary health clinic in the area. The facility is usually staffed by 3 Advanced Nurse Practitioners and 3 Medical Assistants and is open Monday through Friday year-round with limited Saturday hours during summer. The clinic also operates after hours in emergency situations. The borough is also served 24/7 by local EMS. Individuals in need of dire medical attention are transported by air via helicopter or air ambulance to Bartlett Regional Hospital in Juneau (an approximately 45 minute flight). Whitehorse General Hospital in Whitehorse, Yukon is the nearest hospital to Skagway that is accessible by road (an approximately 3 hour drive).

References[edit]

- ^ "Mayor and Assembly". Municipality of Skagway. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ a b June 5, 2008, election, Skaguay News, summer edition, 2008. Page 17.

- ^ a b Thornton, Thomas F. (2004). Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park Ethnographic Overview and Assessment. U.S. Dept. of Interior., at page 53 (“Most [1995-2002 Tlingit-speaking informants] agreed that the name [Shԍagéi] refers to the effect of the strong north wind on the waters of Lynn Canal, which generates rugged seas and ‘wrinkled up’ waves.”).

- ^ Emmons, George T. (unpublished, 1916). History of Tlingit Tribes and Clans. B.C. Archives, reproduced in, Thornton (2004). Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park Ethnographic Overview and Assessment., at page 19 (“[S]he was simply called Skagway [‘the beautiful one’].”).

- ^ See, Edwards, Keri (2010). Dictionary of Tlingit. Sealaska Heritage Institute. ISBN 978-0-9825786-6-7., at page 107 (This verb is used to describe a beautiful woman). A gerund was created by omitting the verb classifier “-l-,” thus rendering a noun. See, Id., at pp. 29-30 (Every Tlingit verb must have a classifier).

- ^ a b Krause, Aurel, and Arthur Krause (1993). To the Chukchi Peninsula and to the Tlingit Indians 1881/1882. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 978-0-912006-66-6. , at pp. 195 (“two bays on our right” [1st = Skagway]), 197-98 (“Kanagu, the stone woman who lives in the first of the above-mentioned bays … is sending one snowstorm after another.”), 230 (“22. [Kanagu is a] mythical woman who is supposed to have turned to stone and unleashes winds when angry; the rock is in the Taiya Valley [sic, ‘Valley’ should be ‘Inlet’].”), 158 (“The god or goddess [Kanagu, note 22], the personified river that empties into the Dejah Valley [sic, ‘Valley’ should be ‘Inlet’]”), 120 and 202 (river name = “Schkaguḗ”); Emmons (1916). History of Tlingit Tribes and Clans, reproduced in, Thornton (2004). Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park Ethnographic Overview and Assessment., at page 19 (Skagway is reportedly derived from the following legend: “[T]he rock wall opened and [Skagway] disappeared forever. But when the North wind blows down from the White Pass, … it was believed to be the breath of her spirit”).

- ^ “Ben” Moore stated that Skagway “is, of course, an Indian name the meaning of which would take too long to explain in detail.” Moore, J. Bernard (1997). Skagway in Days Primeval: The Writings of J. Bernard Moore, 1886-1904. Lynn Canal Publishing. ISBN 0-945284-06-3., between pp. 96-97 (Aug. 2, 1904 Skagway Speech). Ben and his father founded Skagway, Ben’s wife was a Tlingit Indian, and he conducted trade with the Tlingits. The Tlingits apparently explained to him the “long … detail[ed]” meaning of Skagway.

- ^ Thornton, Thomas F. (ed.) (2012). Haa Léelk'w Hás Aaní Saax'ú: Our Grandparents’ Names on the Land. Sealaska Heritage Institute. ISBN 978-0-295-98858-0. , at pp. 52-53 (Face Mountain = Kanagoo’s Image).

- ^ Skaguay News, summer edition, 2008. Page 16.

- ^ "Skagway Alaska". Alaska Trekker.

- ^ Collier's Weekly, 11/09/1901

- ^ Smith, Jeff, Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel, Juneau, Alaska: Klondike Research, 2009. ISBN 0-9819743-0-9

- ^ "Skagway Spectacular Sightseeing Tours, Skagway Tours, Skagway Alaska Tours, Skagway Tour, Skagway Train Ride, White Pass, White Pass Railroad Train Ride, AK". southeasttours.com.

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/klgo/learn/historyculture/jeffsmithsparlor.htm

- ^ "Skagway, Alaska ... Then & Now". Retrieved 2011-02-05.

- ^ "Warren G. Harding - Life Facts". C-SPAN. Archived from the original on 8 July 2000. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "SKAGWAY 2, ALASKA (508528)". Weather Channel. October 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skagway, Alaska. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Skagway. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Skagway. |

- The Municipality of Skagway Borough

- Skagway Chamber of Commerce

- Skagway Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Skagway-Hoonah-Angoon Census Area map, 2000 census: Alaska Department of Labor

- Borough map, 2000 census: Alaska Department of Labor

- Borough map, 2010 census: Alaska Department of Labor

- The Skagway News local newspaper

- Soapy Smith Preservation Trust

- Alaska Community Database Community Information Summaries

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Eric A. Hegg Photographs 736 photographs from 1897 to 1901 documenting the Klondike and Alaska gold rushes, including depictions of frontier life in Skagway and Nome, Alaska and Dawson, Yukon Territory. Keyword search on "Skagway".

- ”Skagway: Gateway to the Klondike”, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Skagway, Alaska at Curlie (based on DMOZ)